The Fifth Servant (49 page)

Authors: Kenneth Wishnia

But the dove found no rest

, he had said, his voice warm and penetrating as he indulged her desires and patiently showed her how to sound out the phrases in the Noah story of the Book of Genesis. Then he explained that this passage also meant that Israel will dwell among the nations, but her people will find no rest among them.

And she relived the moment he first read to her from the Prophets:

But the Lord said to Samuel, Pay no attention to his appearance or his stature

, he said, the holy words resonating around their makeshift study table next to Mrs. Meisel’s pantry, and he prompted her to read the rest. And as she slowly put the sounds together into words, it felt like she was absorbing the greatest magical power ever invented right through her skin. She could feel it suffusing throughout her body and coursing freely through her veins, and she still remembered every word of that passage:

For things are not as man sees them; a person sees only what is visible, but the Lord sees into the heart

.

And when Yankev saw her eyes glistening with emotion, he told her one of his Midrash stories about a princess who married a kind but simple man from a remote village. But the princess was always sad, even though the man always gave her the best bowl of porridge in the village.

Nu? What did he expect? She was a princess!

She had tasted delicacies from all over the world, and she would

never

be satisfied with the “best” porridge his tiny village could offer. In this same way, Yankev explained, man’s eternal soul will never be satisfied with material wealth, because the best this world has to offer can’t compare with the sublime and everlasting beauty of the World-to-Come. And so all those deluded souls who seek to satisfy their earthly appetites with riches and comforts are like that foolish man who could never figure out why the best bowl of porridge he could provide would never satisfy his princess.

The curtain parted and the confessional awaited, dark and beckoning, like the mouth of a subterranean passage to another realm, a portal to another world.

She needed to reach out to that world, and she couldn’t do it by just sitting there feeling sorry for herself.

So Anya got up and left the church. She ran down the steps, sweeping past the beggar as she raced homeward.

She couldn’t do what she needed to do without first letting her parents know where she was going.

But as she turned down the lane where her parents lived, she saw Janoshik standing with the sullen priest he had threatened to denounce her to the day before. Janoshik pointed her out, and when the two men started toward her, a small cry escaped from her lips, and she turned right around and ran straight to the ghetto without looking back.

Smoke was rising in the distance, but it seemed as if the fires had already been extinguished.

She was panting for breath when she reached the East Gate and announced to the stunned guards that she wanted to be allowed inside.

“Huh?”

“You’re sure about this?” they said.

“I am.”

“Because this is a one-way gate, sweetheart.”

“Just let me in.”

They opened the small door a crack, and let her squeeze through the narrow gap and slip inside the ghetto.

She ran through the streets as if guided by some instinctual force until she found Benyamin the shammes. His face was scratched and his muddy clothing smelled of smoke.

“What happened?” she said. “Where’s Yankev? Have you seen him?”

“I’m sorry to have to tell you this,” he said evenly. “He’s been arrested.”

CHAPTER 26

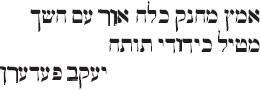

I SMOOTHED OUT THE NOTE as flat as I could on the rabbi’s table, hoping that a couple of missing letters might be revealed in the paper’s creases and bring some sense to the matter. But it didn’t help any. Aside from Federn’s signature at the bottom, the message appeared to be a random string of words:

Be strong

…

stifle

…something…

light together with darkness

…something something something.

“It must be a code of some kind,” said Rabbi Gans.

As soon as the sheriff had escorted us back to the East Gate, I unfolded the note the butcher’s daughter had given me. She must have gotten it from the Janeks, and Rabbi Loew decided on the spot that our first priority was deciphering this strange message, so once again I had to put off talking to Mordecai Meisel about who his biggest debtors were.

“Maybe it’s an acrostic,” said Rabbi Gans.

“I can’t think of any words that start with

amakh

,” I said, stringing together the first three initial letters, or a-m-kh.

or a-m-kh.

“Then maybe it’s an

at-bash

acrostic. In that case, the initial letters would be

tes-khof-mem

—” His voice trailed off. There weren’t any words beginning with that combination, either.

“Or a simple substitution where each letter stands for the one next to it?” I proposed.

Beys-nun-lamed

? Another linguistic dead end.

“First of all, are we sure that’s Federn’s signature?” I asked.

“It certainly looks like it. Besides, who else could have written it?”

Rabbi Loew had been sitting quietly at the table, stroking his beard and studying the document. Our speculations trailed off and we found ourselves paying attention to his silence.

“Take a moment to look at the words,” said Rabbi Loew. “Look at them. Each word has a unique meaning.”

“Forgive me, Rabbi, but how is

oymets

unique?” I said, indicating to the first group of letters. “It appears in many places.”

“As a verb,” said Rabbi Loew. “As a noun it only occurs in one place.”

“But how do we know which it is without context?”

“Here is your context. Look at the next word.”

Oymets

means to show might or courage, as in,

One people shall be mightier than the other

, in

Breyshis

, or,

Only be strong and very courageous,

in Joshua. As a noun, it would mean something like

fortitude

.

The next word was

makhanok

. If I treated it as another verb turned into a noun, then its meaning would shift from

strangle

to

strangulation

. Was this the pattern he wanted me to see? The next word was

kelekh

. I had seen it somewhere before, but I couldn’t remember where. The term was so rare that I had forgotten its meaning. I looked over the rest of the document and confirmed the pattern. Even the phrase

or im khoyshekh

was unusual.

I said, “Each one of these words is extremely rare.”

“Better than that,” said Rabbi Loew. “Each one of these words or phrases occurs only once in the whole of Scripture. Moreover, they all occur in a single book.”

I studied the word formations again, trying to conjure up the relevant phrases. My eye ran over the second word about eight times until I remembered where I had seen it:

My soul craved strangulation, preferred death to life. I loathe it. I shall not live forever; leave me alone, for my days are emptiness

. Only one man in the whole of the Tanakh spoke like that. All the way from the Land of Utz, the man we know as Iyov, whom the Christians call Job.

“All of these words are from the

Seyfer Iyov

.” The Book of Job, which as I recalled, uses

kelekh

to mean both ripe old age and faded strength.

“And the secret to cracking this code is that all these words are unique,” said Rabbi Gans.

“As unique as Job himself,” said Rabbi Loew. “A man so complex he is given more distinctive attributes than our own father Abraham.”

“Complex and bitter,” I said. “But how is that relevant to our situation?”

“Where do you think his bitterness comes from?”

“Where else should it come from? He’s been abandoned by everyone, including his wife.”

“Not so. His three friends remain,” said Rabbi Gans.

Friends who only know how to talk, not to listen

.

“More than that,” said Rabbi Loew, “Job admits that he has never felt secure, or at peace, that he has lived his life in constant fear of disaster in a world that is ruled by blind fate rather than a just God. He still doesn’t realize that God may have chosen to increase his suffering in order to teach him something, the same way that a little discipline is good for a child’s education.”

“You don’t learn anything by getting smacked,” I said. “It doesn’t teach you anything except how much it hurts to get smacked.”

Rabbi Loew sat there tapping his middle finger and avoiding eye contact. “You have a great deal of the serpent’s bile in your innards, Ben-Akiva. And you mustn’t let it eat away at you. Look at these other words—

or im khoyshekh, metil, kidoydey, soysokh

. They refer to eternity and to God’s most powerful earthly creatures, the gentle beast known as Behemoth and the terrible serpent whose name is Livyoson.”

Or, the Leviathan.

“But nobody is even sure what

metil

means,” I protested. “Rashi calls it a

burden

and Ramban calls it a

sledgehammer

.

Kidoydey

probably means sparks,

soysokh

some kind of slingstones or catapult. What does that have to do with—”

The dragon-like creature from my dream

.

Rabbi Loew nodded as if he had read my mind. “Perhaps now we can begin to interpret your dream, my

talmid

. Ramban says that we will curse the day that man’s destructive nature wakes the fearsome Livyoson from his slumber. But God makes a promise that whoever takes on the challenge of fighting the Livyoson shall be rewarded.”

“Fight the Livyoson?” I said.

Canst thou draw out Livyoson with a hook, or press his tongue down with a cord? Canst thou put a hook into his nose? Who can pry open the doors of his face? His fangs are terrible all around. Flames spew from his mouth,

kidoydey

leap out. Strength lives in his neck. He treats iron like straw, brass like rotted wood. He will not flee before an arrow. He looks upon the

soysokh

as so much straw, he laughs at the shaking of a spear.