The Fence: A Police Cover-Up Along Boston's Racial Divide (33 page)

Read The Fence: A Police Cover-Up Along Boston's Racial Divide Online

Authors: Dick Lehr

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Political Science, #Social Science, #Law Enforcement, #True Crime, #Criminology, #Ethnic Studies, #African Americans, #Police Misconduct, #African American Studies, #Police Brutality, #Boston (Mass.), #Discrimination & Race Relations, #African American Police

Kenny Conley back on the force.

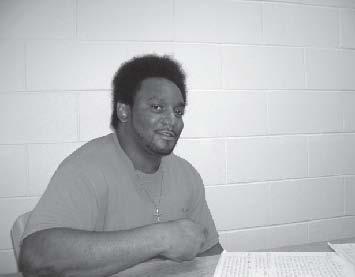

Smut Brown today in a Maine prison.

Justice Denied, Then the Trial

The White Guy at the Fence

B

y the time he appeared before Bob Peabody’s grand jury in December, Dave Williams was likely feeling more emboldened than ever. He’d come up with explanations for the incriminating utterances he’d made the night of the beating, had stuck to them during repeated questioning, and had not faced any heat. In fact, the worst that had happened was being named in Mike Cox’s civil rights lawsuit, and Williams let Mike know what he thought about that.

He called Mike after receiving notice of the lawsuit. “I got something in the mail.”

“Yeah, I assumed you would,” Mike said.

Mike was at his desk in the Internal Affairs office. Williams said he wanted to see him right away. “Well, I’m here,” Mike said.

Without hesitation, Williams marched into Internal Affairs. He asked what Mike was up to suing him and the department. He reiterated his talking points from their chance encounter in Franklin Park: You know I know you, he said.

Yeah, Mike said, he knew all that.

“I hope you don’t think I hit you,” Williams said.

“Just do the right thing,” Mike said.

Williams grew agitated. Right thing? Right thing? “Fuck everybody,” he said.

“You should fuck everybody,” Mike said. He told Williams he did not owe anyone anything. “So why cover for them?”

They talked in circles and then Williams left. It took Mike a few minutes to fathom the strangeness of the moment: a prime suspect in the beating challenging the beating victim in the offices of Internal Affairs. And it turned out Mike’s boss, Deputy Superintendent Ann Marie Doherty, had even spotted Williams. But she did not intervene and merely told Mike later that William’s presence was not appropriate.

Williams had dug in and was now on a roll. It seemed even when he lost, he won. He got the result of the last excessive force case pending against him, the one involving teenager Valdir Fernandes, who claimed to Internal Affairs and in a lawsuit that Williams slapped him around on his porch. Williams learned he’d been found guilty of physically abusing the teenager. Two officers had backed Williams, brazenly submitting reports that were virtually identical, except for signatures and a few token changes in wording and grammar. But there was a glitch; the identical accounts didn’t quiet line up with Williams’s. The two noted that Williams, after the boy spit near him, “grabbed Valdir above the jacket.” Williams, in his report, never mentioned touching the boy at all. The discrepancy was enough for the Internal Affairs investigator to rule that Dave Williams’s account was “less credible” than the boy’s. Making matters worse were the photographs of the boy showing “bruises consistent with being slapped in the face.”

For once it looked bad. But appearances were deceiving. Once again, even an adverse result proved much ado about nothing. No disciplinary action was taken against Williams, and, eventually, the city paid Valdir Fernandes $7,000 in a settlement to end the lawsuit against the police.

Two months after making the Hail Mary proposal to his boss, Bob Peabody got his wish in early 1996 to take a final run at Dave Williams. He and Lieutenant Detective Paul Farrahar arrived at Williams’s lawyer’s office, located in a building near Quincy Market, the popular shopping area in the shadow of the elevated Southeast Expressway that cut through Boston’s downtown, on a gray February day.

Waiting in a windowless conference room was Williams and his attorney, Carol S. Ball. Peabody had known Ball for years; she was a former assistant district attorney and he’d long admired her feisty, high-energy advocacy. “I could talk to her and vice versa, and so I asked for this audience.” The meeting had come together quickly. Ball had been named to the bench and would soon leave her practice to become a Superior Court judge. She would have to quit representing Williams—and, for that matter, all her clients.

The ground rules were simple: The session was unofficial and off the record. Peabody’s hope was to persuade Williams to come around. He and Farrahar decided beforehand to do the “good cop, bad cop thing,” with Peabody playing the role of bad cop. His approach would be: “C’mon, Dave, here’s your chance. Tell us what happened. I think you know more. I think you saw more.”

The prosecutor began by explaining why he’d asked for the meeting. He told Williams his story about chasing Marquis Evans was contradicted by two other police officers. He urged Williams to “come clean rather than protect his partner that night.”

But Williams was unmoved. “He was terse,” Peabody said later. “He’s a big man. I’m a big man, too, but I’m not as big as he is, not as wide. He just said, ‘That’s all I know.’” It was as if Williams was saying: You’re not intimidating me with your hardball stuff.

Peabody quickly saw the last-ditch tactic was a bust. “We weren’t getting anywhere,” he said. “I just couldn’t crack him.” Reluctantly, he threw in the towel.

“It was a short meeting.”

Peabody’s last hope was Ian Daley, who initially struggled and asked Jimmy Rattigan for advice about what to do, but then clammed up. Like Jimmy Burgio, Daley invoked the Fifth Amendment when summoned to meet with Anti-Corruption investigators during the summertime. But by early March 1996, Peabody was talking with Daley’s lawyer, trying to turn Daley into a cooperating witness. Peabody believed Daley had had a “ringside seat” at the dead end and, if Peabody could flip him, Daley would make an ideal witness.

Peabody and Daley’s attorney, a former local prosecutor named Tom Hoopes, went back and forth. Hoopes was a seasoned practitioner. Before making any deal, he wanted Peabody to reveal the evidence gathered against his client. He demanded that Peabody actually let him read the transcripts of the secret grand jury testimony.

Hoopes wanted, in short, to see Peabody’s hand in what amounted to a legal poker game. He was doing what most any defense attorney would do—consider cutting a deal that would minimize or even eliminate criminal liability in return for the client’s testimony. His primary legal responsibility was protecting his client from criminal charges. But in this instance there was a second and nearly equal concern weighing heavily against any form of cooperation. Cops don’t want to testify against other cops; to do so was tantamount to professional suicide. But there was a scenario that could justify Daley becoming a witness: if other cops had already started talking and were hurling accusations against him. Under those circumstances, Daley could explain he hadn’t run to the courthouse and been the first cop to make a deal; he’d done so reluctantly and only to defend himself. Most cops would understand that.

Jockeying with Peabody, Hoopes had to keep all this in mind. He needed to know what Peabody had on his client, and, to get that, he indicated that Daley was considering a deal. What, if anything, had other cops said against his client? Had anyone gone so far as to finger Daley in the beating? Hoopes needed answers. He swung by Peabody’s office on the first Monday in March, and the two lawyers discussed the Cox investigation.

Peabody, afterward, wrote his supervisor an e-mail. “He has revised his latest demand to view GJ testimony re: his client’s (Daley) involvement,” he wrote. “Instead, he asks that I give him an oral summary of what evidence (to date) impacts his client and/or how he is involved.” It may have been wishful thinking, but Peabody said from talking to Hoopes, “I got the impression that Daley may want to cooperate.”

If true, Peabody saw a huge upside. Hoopes, in the give-and-take, said his client would be able to get Peabody “halfway there” in solving the assault, but that he was unable to “name names.” Peabody wasn’t sure what this meant. Did it mean Daley was not able to provide a specific blow-by-blow—saying which cop hit Mike first, dragged him from the fence, and so forth—but that Daley had seen the beating and could identify the assailants, if not by name then by description? Or did it mean Daley had not witnessed the actual beating, but, seconds afterward, saw the cops who’d done it standing right there talking about their brutal handiwork? Peabody may not have known the answers, but he was sure of one thing: Daley was a valuable witness whose cooperation he wanted.

But Peabody was also aware of the risk of telling all. “The downside,” he wrote, “is that he will see our cards and, now knowing he’s safe, keeps silent.” The prosecutor was at a crossroads, desperate even. “I think we should comply with his request,” he recommended, and got the okay.

Peabody disclosed to Hoopes that no one was accusing Daley of beating Mike and he had no evidence to charge him. Weeks went by, and Peabody heard nothing back. In early April, after nearly a month, he called Hoopes. Was Daley going to play? He pressed for an answer. Then Hoopes delivered the bad news—thanks, but no thanks. Peabody reported the devastating kiss-off in another e-mail to his boss, the DA Ralph Martin. “Daley said NO despite having the unusual benefit of knowing almost everything our investigation has learned to date about the events of January 25, 1995.” Peabody’s worst-case scenario had indeed come to pass. He’d been outmaneuvered—baited, in effect—by the long shot he’d get Daley to cooperate. For Daley, it was a no-brainer. Why stick his neck out? In a game where justice had taken a backseat, he had no incentive to break his silence. Peabody had nothing on him.

“The test of loyalty oftentimes on police departments,” a Boston police official once said, “is, number one: Will you lie for me? And if you won’t lie for me, will you at least be silent?” In short order, the frustrated Peabody had suffered a wrenching one-two punch from Dave Williams and Ian Daley, the two cops he considered key to his prosecution. “You could tell Williams and Daley knew more,” he said. “I couldn’t get either of them to take it to the next level.” Peabody was not sure what more he could do.

“We’ve sort of run out of gas.”

While Bob Peabody was realizing a year into the investigation that he was spinning his wheels, his colleagues happened to be on the losing end of a courtroom battle against another Boston police officer accused of corruption. The cop had been charged with stealing $6,352 in cash from a wallet a civilian turned in to police after finding it on the lobby floor of her apartment building. The officer insisted he had not stolen the money. He’d left the wallet on the counter, he said, and while he was attending to another matter, an unidentified man came into the station and took the cash. The officer certainly seemed caught in a bind prior to the trial—trouble of his own making. Investigators uncovered two incident reports he’d written. The first recorded receipt of the wallet, the $6,352, a Hermès watch, and an airline boarding pass. The second, replacing the first, mentioned a wallet, the watch, and the boarding pass—but no cash. Taking the stand to defend himself, the officer testified he wrote the second report not because he stole the money but to cover up the embarrassment of leaving the wallet on the counter. He was guilty of a lie, not larceny. The jury agreed, and, on a Friday in late April, the officer was acquitted.

The media called the verdict a “stinging defeat to Suffolk County prosecutors,” a reference to Ralph Martin’s losing track record against Boston cops suspected of wrongdoing. Earlier that year, a judge had thrown out the case charging a cop with raping a prostitute with a nasty public rebuke, and now this losing trial verdict. Not surprisingly, Tom Drechsler represented the cops in both cases, the lawyer of choice for cops in trouble. Jimmy Burgio’s attorney was fast establishing himself as Martin’s nemesis.

In the weeks following this latest setback, Martin entered into discussions with the U.S. attorney’s office in Boston about federal prosecutors taking over the Cox investigation. Peabody had not been able to uncover the kind of evidence he believed necessary to convict cops responsible for Mike’s injuries. Bob Peabody needed eyewitnesses. “We didn’t have anybody saying, ‘It was him, it was him, it was him.’” It was no longer enough to build a circumstantial case, not in the hothouse atmosphere of cop cases. “You want slam-dunk evidence,” Peabody said. “We certainly didn’t have it.”

Having come up empty, Peabody began directing his focus elsewhere. He was assigned to prosecute an electrician charged with involuntary manslaughter after three children died in a house fire sparked by the electrician’s faulty wiring. It was a complicated case, and Peabody started preparing for the trial in early January, when he would argue that the electrician’s work in a basement apartment was so atrocious and careless he should be held criminally responsible. Peabody’s career also took an important turn. Working alongside federal prosecutors in the Charlestown “code of silence” racketeering case, he’d made a strong impression. He was offered a job as an assistant U.S. attorney and would be leaving Martin’s office.

Nonetheless, Bob Peabody continued to chase a lead or two in the Cox case. One involved the municipal police officers. He got word one munie was overheard telling another, “You shouldn’t have hit him so hard.” He conducted interviews, but decided quickly the line was locker room banter. “Gallows humor,” he said. The remainder of 1996 was mainly about preparing for the electrician’s trial—his last as an assistant district attorney—and boxing up his Cox files for federal prosecutors. Maybe the feds would have better luck breaking down the police culture and getting cops to talk.