The Female Brain (2 page)

Authors: Louann Md Brizendine

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Psychology & Counseling, #Neuropsychology, #Personality, #Women's Health, #General, #Medical Books, #Psychology, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Science & Math, #Biological Sciences, #Biology, #Personal Health, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Internal Medicine, #Neurology, #Neuroscience

(in other words, how hormones affect a woman’s brain)

T

HE ONES YOUR

doctor knows about

E

STROGEN

—the queen: powerful, in control, all-consuming; sometimes all business, sometimes an aggressive seductress; friend of dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin, acetylcholine, and norepinephrine (the feel-good brain chemicals).

P

ROGESTERONE

—in the background but a powerful sister to estrogen; intermittently appears and sometimes is a storm cloud reversing the effects of estrogen; other times is a mellowing agent; mother of allopregnenolone (the brain’s Valium, i.e., chill pill).

T

ESTOSTERONE

—fast, assertive, focused, all-consuming, masculine; forceful seducer; aggressive, unfeeling; has no time for cuddling.

T

HE ONES YOUR

doctor may not know about that also affect a woman’s brain

O

XYTOCIN

—fluffy, purring kitty; cuddly, nurturing, earth mother; the good witch Glinda in

The Wizard of Oz;

finds pleasure in helping and serving; sister to vasopressin (the male socializing hormone), sister to estrogen, friend of dopamine (another feel-good brain chemical).

C

ORTISOL

—frizzled, frazzled, stressed out; highly sensitive, physically and emotionally.

V

ASOPRESSIN

—secretive, in the background, subtle aggressive male energies; brother to testosterone, brother to oxytocin (makes you want to connect in an active, male way, as does oxytocin).

DHEA

—reservoir of all the hormones; omnipresent, pervasive, sustaining mist of life; energizing; father and mother of testosterone and estrogen, nicknamed “the mother hormone,” the Zeus and Hera of hormones; robustly present in youth, wanes to nothing in old age.

A

NDROSTENEDIONE

—the mother of testosterone in the ovaries; supply of sassiness; high-spirited in youth, wanes at menopause, dies with the ovaries.

A

LLOPREGNENOLONE

—the luxurious, soothing, mellowing daughter of progesterone; without her, we are crabby; she is sedating, calming, easing; neutralizes any stress, but as soon as she leaves, all is irritable withdrawal; her sudden departure is the central story of PMS, the three or four days before a woman’s period starts.

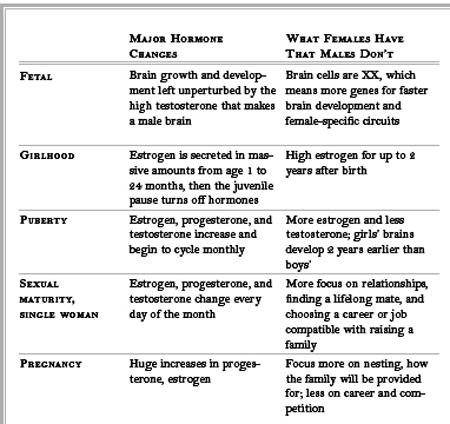

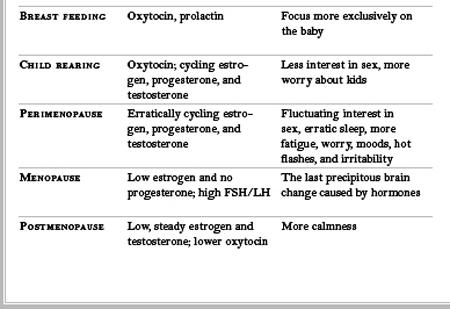

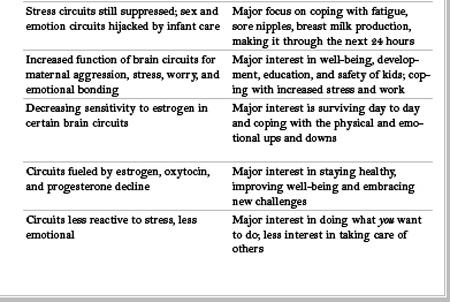

PHASES OF

A FEMALE’S LIFE

H

ORMONES CAN DETERMINE

what the brain is interested in doing. They help guide nurturing, social, sexual, and aggressive behaviors. They can affect being talkative, being flirtatious, giving or attending parties, writing thank-you notes, planning children’s play dates, cuddling, grooming, worrying about hurting the feelings of others, being competitive, masturbating and initiating sex.

INTRODUCTION

What Makes Us Women

M

ORE THAN

99 percent of male and female genetic coding is exactly the same. Out of the thirty thousand genes in the human genome, the less than one percent variation between the sexes is small. But that percentage difference influences every single cell in our bodies—from the nerves that register pleasure and pain to the neurons that transmit perception, thoughts, feelings, and emotions.

To the observing eye, the brains of females and males are not the same. Male brains are larger by about 9 percent, even after correcting for body size. In the nineteenth century, scientists took this to mean that women had less mental capacity than men. Women and men, however, have the same number of brain cells. The cells are just packed more densely in women—cinched corsetlike into a smaller skull.

For much of the twentieth century, most scientists assumed that women were essentially small men, neurologically and in every other sense except for their reproductive functions. That assumption has been at the heart of enduring misunderstandings about female psychology and physiology. When you look a little deeper into the brain differences, they reveal what makes women women and men men.

Until the 1990s, researchers paid little attention to female physiology, neuroanatomy, or psychology separate from that of men. I saw this oversight firsthand during my undergraduate years in neurobiology at Berkeley in the 1970s, during my medical education at Yale, and during my training in psychiatry at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center at Harvard Medical School. While enrolled at each of these institutions, I learned little or nothing about female biological or neurological difference outside of pregnancy. When a professor presented a study about animal behavior one day at Yale, I raised my hand and asked what the research findings were for females in that study. The male professor dismissed my question, stating, “We never use females in these studies—their menstrual cycles would just mess up the data.”

The little research that was available, however, suggested that the brain differences, though subtle, were profound. As a resident in psychiatry, I became fascinated by the fact that there was a two-to-one ratio of depression in women compared with men. No one was offering any clear reasons for this discrepancy. Because I had gone to college at the peak of the feminist movement, my personal explanations ran toward the political and the psychological. I took the typical 1970s stance that the patriarchy of Western culture must have been the culprit. It must have kept women down and made them less functional than men. But that explanation alone didn’t seem to fit: new studies were uncovering the same depression ratio worldwide. I started to think that something bigger, more basic and biological, was going on.

One day it struck me that male versus female depression rates didn’t start to diverge until females turned twelve or thirteen—the age girls began menstruating. It appeared that the chemical changes at puberty did something in the brain to trigger more depression in women. Few scientists at the time were researching this link, and most psychiatrists, like me, had been trained in traditional psychoanalytic theory, which examined childhood experience but never considered that specific female brain chemistry might be involved. When I started taking a woman’s hormonal state into account as I evaluated her psychiatrically, I discovered the massive neurological effects her hormones have during different stages of life in shaping her desires, her values, and the very way she perceives reality.

My first epiphany about the different realities created by sex hormones came when I started treating women with what I call extreme premenstrual brain syndrome. In all menstruating women, the female brain changes a little every day. Some parts of the brain change up to 25 percent every month. Things get rocky at times, but for most women, the changes are manageable. Some of my patients, though, came to me feeling so jerked around by their hormones on some days that they couldn’t work or speak to anyone because they’d either burst into tears or bite someone’s head off. Most weeks of the month they were engaged, intelligent, productive, and optimistic, but a mere shift in the hormonal flood to their brains on certain days left them feeling that the future looked bleak, and that they hated themselves and their lives. These thoughts felt real and solid, and these women acted on them as though they were reality and would last forever—even though they arose solely from hormonal shifts in their brains. As soon as the tides changed, they were back to their best selves. This extreme form of PMS, which is present in only a few percent of women, introduced me to how the female brain’s reality can turn on a dime.

If a woman’s reality could change radically from week to week, the same would have to be true of the massive hormonal changes that occur throughout a woman’s life. I wanted the chance to find out more about these possibilities on a broader scale, and so, in 1994, I founded the Women’s Mood and Hormone Clinic in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. It was one of the first clinics in the country dedicated to looking at women’s brain states, and how neurochemistry and hormones affect their moods.