The Family (25 page)

Authors: David Laskin

“I went to the World's Fair and I saw everything,” Shalom Tvi wrote to Sonia and Chaim. “I saw everything but you, my dear children. You, I could not find there. To tell the truth, I already miss home. But I feel that I'm obligated to spend the time here.”

â

In the last week of August, Shalom Tvi went to the shipping company in Manhattan to inquire about his return passage. He was booked on a ship

due to sail back to Poland on October 1, but the clerk told him that if war broke out before that he must apply to the Immigration and Naturalization Service for an extension of his visa. “I am confused,” Shalom Tvi wrote Sonia. “I don't know what God may bring or whether he plans to sweeten our lives with any pleasure.”

Just before the start of September he traveled up to Stamford, Connecticut, to stay with his youngest brother, Herman, for a few days before continuing on to Hayim Yehoshua's place in New Haven. On the last day of August, he sat down to write to Sonia and Chaim from New Haven about how worried he was about the danger of war. “First, because we have separated from each other in such uncertain times and second, who knows what will happen to Shepseleh and Khost.”

Shalom Tvi was right to be worried. By the time he went to bed that night, German tanks and troops were crossing the border into Poland and hundreds of Luftwaffe planes were dropping bombs on Poland's major cities. Hayim Yehoshua kept a radio in his living room, and on the morning of September 1, the whole family stood and stared at the floor while the crackling voice of the announcer shrilled at them.

The Wehrmacht is on the move, Poland is in flames, but the Polish army has been mobilized and resistance is expected to be stiff

.

â

To my dear and beloved wife Beyle and to my dear children Etl, Khost and Mireleh:

Be healthy and may God shield you from all calamities.

I am writing to you with a broken heart from the disaster that has happened to the world and especially to us. I am left severed from you and I cannot even send letters. I will try to send this through Eretz Israel, and maybe it will arrive.

I don't know what will happen to you. Will all of you be in Vilna or stay in Rakov? I hope that you will live together, my dear and beloved ones. I had hoped that we could see each other soon, but now only God knows when this will happen.

May all of you be together and healthy and may Khost and Shepseleh

not be taken from you. I am going around crushed by a weight of anxiety. Everyone here sits by the radio all day long.

May this letter reach you. This is my only comfort. Everyone here prays to God that He will defeat the dog Hitler.

From me, your husband and father, Shalom Tvi

SECOND WORLD WAR

D

oba was still a young womanâonly thirty-seven years oldâin 1939, but she was emotional and high-strung and a bit of a hypochondriac. Motherhood, her greatest joy, was also the source of endless upset, which no doubt contributed to her attacks of nerves and ill health. If Shimonkeh or Velveleh so much as skinned a knee, Doba flew into a passion; when Shimonkeh nearly died of scarlet fever the summer Sonia made aliyah, no one could breathe a word to pregnant Doba, lest she become unhinged. With so much angst fluttering her heart, Doba was forever craving rest and relaxation. When her in-laws offered her and Shepseleh and the boys use of a cottage that they had rented in the spa town of Druskininkai that summer, Doba jumped at it. Druskininkai's mineral baths were renowned; the country air would do all of them good; there was a hammock stretched between two trees where they could take turns snoozing on warm afternoons. Doba decided that she would spend the entire summer there and, after some cajoling, she prevailed on her mother to join her. After all, Shalom Tvi was in America and the leather business had been sold, so for the first time in her life Beyle was free to leave Rakov and do what she wanted. What better occasion for a nice long stay in the country?

Beyle joined Doba's family at the spa right after Shalom Tvi's departure

at the start of July and stuck it out at Druskininkai for as long as she could stand it. She took the waters; she tried to sleep in the hammock; she sat in the shade; she watched Shimonkeh, now eleven years old, ride his bike and Velveleh, seven, sit with his father and move wooden pieces around the chessboard. She wrote letters to her husband and bustled around the kitchen. She went to shul on Saturday with Doba. But five weeks in, Beyle decided that she had had enough. After more than forty years of hard work, idleness did not come easily. She wanted to be home. It was arranged that Beyle would depart and that Etl, Khost, and Mireleh would take her place in the Druskininkai cottage for a few weeks' vacation. By August 21, Beyle was back in Rakov writing to Sonia and Chaim about how healthy she felt after taking the waters and how glad she was that Etl's family had a chance to relax at the spa before Khost started another busy year teaching school.

It was only because Khost was away in Druskininkai that he avoided being called up by the Polish army when the Germans attacked on the morning of September 1.

With the outbreak of war, there was no question that they must leave Druskininkai immediatelyâbut where should they go? The two couples sized up the situation anxiously. Clearly, Etl and Khost would return to RakovâMother could not be left alone and Khost had a job there. But what about Doba, Shepseleh, and the boys? Wouldn't it be better for them to come to Rakov too so the family could all be together? They didn't have long to debate itâthey must get out before the roads became impassable and the rail lines were bombed. In the event, they decided that their two families should separate, reasoning that if they were in different places they would have a better chance of keeping some line of communication open with Sonia in Palestine and Father in America.

The little rail station outside of Druskininkai was pandemonium, but somehow the two couples shoved their children and luggage onto separate trains and somehow the trains got through to Vilna and to Olechnowicze, the station closest to Rakov. Thank God, they thought, that Rakov and Vilna were in the east of Poland, far from the Nazi invaders. (Rakov and Vilna had been incorporated into the newly formed Polish state in the 1920s, so when the war broke out, the members of both families were Polish citizens.) Thank God that on September 3, Britain and France declared

war on Germany. Thank God that Poland had an army, an air force, tanks, modern weapons, the will to fight. Doba wept with joy when they opened the door to their flat near the Dawn Gate and saw that all was exactly as they had left it in June.

Then came the first German bombing raids. Sirens wailing in the streetâscreams and shouts in the hallwayâthe pounding of shoes on the stairs as the neighbors fled to the cellar. Doba and Shepseleh leapt out of bed, woke the boys, and fled downstairs with the others. They cowered in the dark and strained their ears for the thud of explosions. They huddled together trembling until the all-clear sounded. When they returned to their flat, their hearts were racing, sleep impossible. In the morning, Doba and Shepseleh dragged themselves out of bed hollow-eyed and desperate for news.

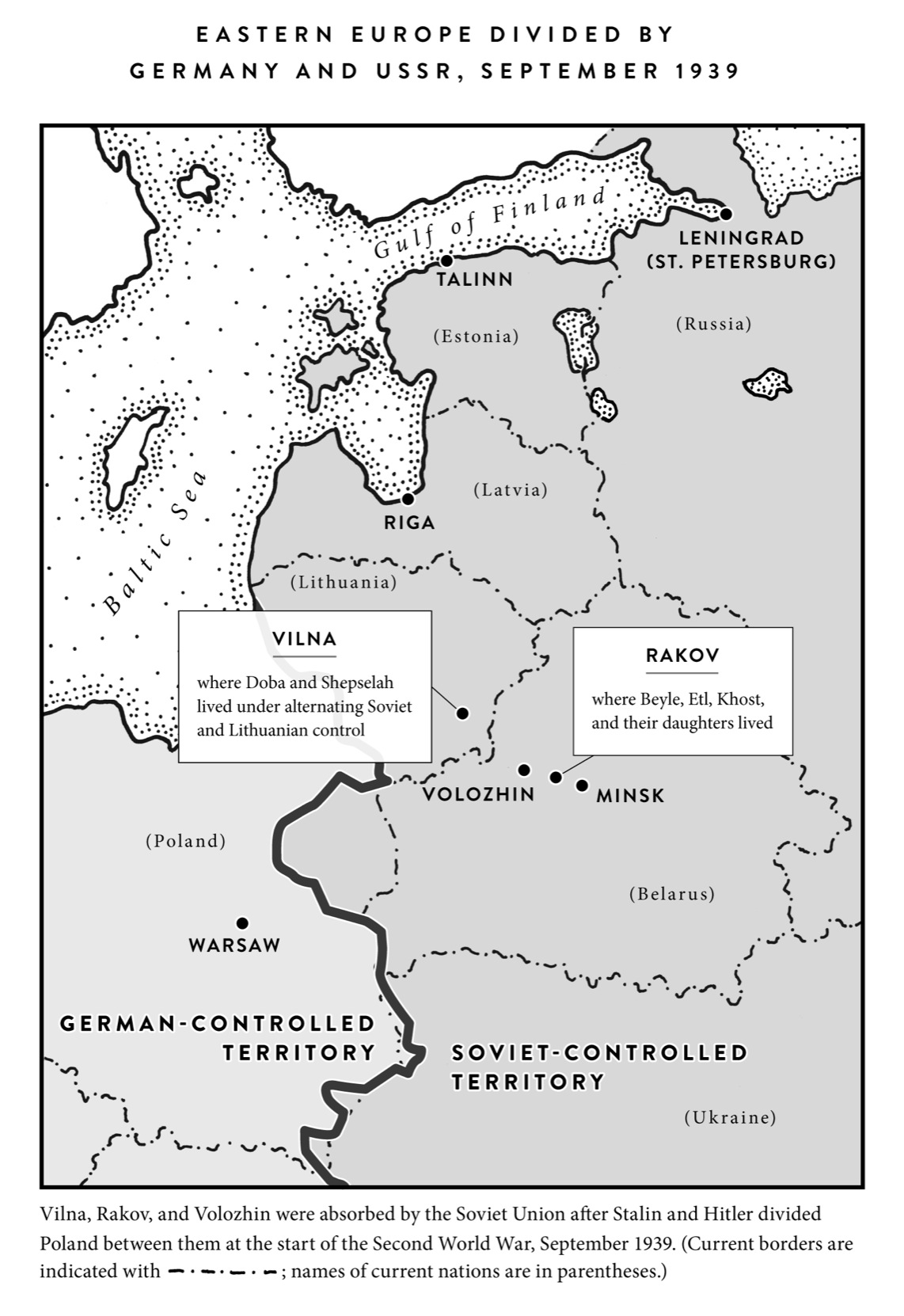

It came thick and fast in those September days and none of it was good. Britain and France were technically at war with Germany but they did nothing to help Poland. The Polish retreat from the western border had turned into a rout. The Wehrmacht seemed to be everywhere and unstoppable. The Luftwaffe dominated the skies. By September 14, Poland's air force had been effectively disabled. Sixty German divisions were converging on Warsaw, and German planes, unchallenged, were bombing every major city in the country. In the general mobilization, Khost was called up for service with the Polish army. (Shepseleh, though subject to the draft as a citizen of Poland, was spared.) Etl had no idea where her husband was being sent or when he would return. The news that arrived on September 17 baffled all of them: the Russians were now attacking Poland from the east. Evidently, the Nazis and the Soviets were allies in this new warâit made no sense, but that's how it was. Only later did it emerge that Hitler and Stalin, by the terms of a secret nonaggression pact worked out by their foreign ministers, Ribbentrop and Molotov, at the end of August, had agreed to carve up Poland between them. Hitler took the west, including Warsaw, Lodz, Cracow, and Lublin; Stalin got the east, with Lithuania thrown in as a “Soviet zone of interest.” In this new division of Poland, Rakov was Russian once again; and

Vilna, which had flown God knows how many flags in the past twenty years, became Russian again too, at least for the time being.

As quickly as it started, the war seemed to be over. The bombing stopped in Vilna. Blackout curtains were removed; street lamps were lit again at night. Shimonkeh and Velveleh slept all night in their own beds. Polish troops started to trickle back, many passing through Vilna on their way home. “I cried when we saw soldiers returning and Khost was not among them,” Doba wrote her father. She and Shepseleh feared the worst, but God was merciful.

November 28, 1939

Dear Father,

I have much to tell you, but it is hard to do in a single letter. I have written to you before that Khost had been drafted to the Army. Now I can tell you that he has come backâfirst to Vilna and from here he returned to Rakov. You cannot imagine how happy we were when we saw him.

He was lucky. He was with us at Druskininkai and therefore reported for duty a bit later. That changed the whole situation. Shepseleh worried that if “the big ones” [i.e., the Russians] had not come, his fate would have been the same. The fact that we can joke about it is a good sign. So you don't have to worry about our men, or the rest of us. We were very glad to see the “big ones” because we had been weary of staying days and nights with the children in the basement.

The real problem now is that there is not enough money. Zloties [the Polish currency] are worth nothing. Shepleseh does not have work. The office has shrunk. Only a few workers were left and it is hard to find work. The big firms are no more. Everything has changed suddenly.

Who could imagine that such a situation could ever happen? Briefly, dear father, we are left with no means of livelihood. What I have written is only a drop in the sea. What you read in the papers is nothing in comparison to what has happened here in only three weeks.

I envy the Americans their peaceful life. They cannot fathom what is happening here and in the rest of the world.

Love, Doba

â

The situation in Vilna remained volatile. The Soviets had seized the city on September 19, two days after they invaded Poland, but they agreed to turn it over to Lithuania at the end of October on the condition that 20,000 Red Army troops be permitted to remain in Soviet bases on Lithuanian soil. In the final days of the Soviet occupation, civic life collapsed. The

Forward

reported that “

Vilna is congested with refugees and its population suffers hunger and privation; economic life has come to a halt and many Jews wander the streets begging for a piece of bread.” The Soviet pullout triggered a three-day pogrom. Vilna's Polish and Lithuanian population beat Jews in the street,

wounding 200 and killing 1; scores of Jewish shops were vandalized; a policeman was killed. A typhus epidemic broke out and hospitals overflowed (Lithuanians claimed that disgruntled Poles had triggered the epidemic by cutting the city's water supply, while Poles insisted that

Volksdeutsche

âGerman nationals residing in Vilnaâhad connected sewer pipes to the municipal water supply).

Meanwhile, 14,000 Jewish refugees from Poland's German-occupied sector streamed inâamong them “the spiritual elite of Polish Jewry” including 2,000

halutzim

, 2,440 rabbinical students, 171 rabbis, and assorted Bundists, teachers, journalists, and scientists whom the Nazis had expelled. The refugees survived on charity distributed by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (“the Joint”), but Vilna's non-refugee Jewish residents were on their own. “

The food supply is being rapidly depleted,” wrote one resident. “One must brace oneself to acquire a little butter and some eggs. The queue for these items is enormous. . . . It is pointless to join the queue at 6

A.M.

, for by that time thousands wait at the door.” White-collar workers who had been accustomed to conducting business in Polish, Russian, and Yiddish were laid off in droves because they could not speak Lithuanian, the new official language. Shepseleh, now forty-two years old, joined the ghosts who haunted the streets looking for work.

My dear Father-in-law Shalom Tvi,

The big problem is that it is hard these days to find work. I traveled to Kovno [the Yiddish name for Kaunas, Lithuania's second-largest city

and the temporary capital during the interwar period] to see if I could find something. I spent money for the trip but found nothing. All the big companies have lost everything, and there is no one to turn to. Of course, the idleness causes the money to dwindle away and the cost of living has gone up. We still have food and do not suffer, but when I think of the future, I feel like my brain is exploding. To stay sane and healthy, it is better to not think too much. Who knew that the situation would deteriorate so fast?

You know, father, that I am not one to make life difficult, so if I allow myself to write to you like this, it shows that I am totally broken. Though truthfully, others have bigger problems. There are people who were well-to-do in the past who have no roofs over their heads. There are those who have lost a relative. So we should be satisfied with our lot and not complain.

Father, please write to us in detail about yourself, about Reb Avram Akiva and his family and about Hayim Yehoshua and his family. If you have not yet received our letter, I am reminding you that the money you sent has arrived and we thank you and uncle from the bottom of our hearts. Write to us what is happening with the visa. We can no longer take care of it from here. Maybe you can handle it.

Your son-in-law Shepseleh

For the family, there was one ray of light that dark season: on November 28, Sonia gave birth to a son. They named him Arie, for Chaim's late father, though they called him Areleh as a baby and Arik when he was older. As he grew, no one could understand where the child had come by his looksâbronze, athletic, chiseled, a lanky golden boy in a short dark family. It was as if some warrior gene, after skipping many generations, had surfaced under the fierce Mediterranean sun.

“Mazal Tov, Mazal Tov, with God's will may the tender born son bring luck, blessing and peace to the world,” Shalom Tvi wrote his daughter and son-in-law from New York. “May you raise him easily and may he merit a long life.” Shalom Tvi sent Sonia not only blessings and prayers but a steady

stream of packagesâhand-me-down clothing from the rich American relatives (“here one wears clothes a few times and then they discover a new fashion, discard the garment and buy something new”), money, even the occasional brooch or necklace. Sonia's insistence that she had no need for jewelry puzzled her father. “Is it forbidden to wear jewelry there?” he demanded. “Surely women in the big cities wear jewelry even in Palestine.” Jewelry was the last thing on Sonia's mind in those days. She had a toddler, not yet five, and a newborn but no refrigerator; their cow ate voraciously but provided only a trickle of milk; she worried about Arab attacks every night when Chaim drove the truck and was late getting home.

We'll come when it's quiet

, her mother and sisters used to reply when Sonia urged them to join her in Kfar Vitkinâ

quiet

was their euphemism for peaceful, free of violenceâbut it was never quiet in the Land. Now Europe wasn't quiet either. For as long as this war lasted, Sonia knew there was no hope of getting her mother or sisters out of Poland and into Palestine. She was on her own with two small children, a stingy cow, a tiny house baking in the sun, meat and cheese spoiling in the heat, an antiquated ringer washer, hostile Arabs over the next dune, and the cowardly British government that valued oil more than human life.