The Falls (62 page)

Authors: Ian Rankin

He pointed a finger at her. ‘You’re lucky I didn’t tag you sooner. I might have said something to Donald Devlin. And then you’d look like Jean back there, if not a damned sight worse.’

He turned away, headed back to the car. On the way, he unhooked the ‘Pottery’ sign and tossed it into the gutter. She was still watching from her doorway as he started the ignition. A couple of day-trippers were approaching along the pavement. Rebus knew exactly where they were headed and why. He made sure to turn the steering-wheel hard, running the sign over, front and back tyres both.

On the way back into Edinburgh, Jean asked if they were going to Portobello. He nodded, and asked if that was okay with her.

‘It’s fine,’ she told him. ‘I need someone to help me move that mirror out of the bedroom.’ He looked at her. ‘Just until the bruises have healed,’ she said quietly.

He nodded his understanding. ‘Know what I need, Jean?’

She turned towards him. ‘What?’

He shook his head slowly. ‘I was hoping you might tell me …’

Sexual repression and hysteria are what Edinburgh is all about.

Afterword

Firstly, a big thank-you to Mogwai, whose ‘Stanley Kubrick’ EP was playing in the background throughout the final draft of this book.

The collection of poetry in David Costello’s flat is

I Dream of Alfred Hitchcock

by James Robertson, and the poem from which Rebus quotes is entitled ‘Shower Scene’.

After the first draft of this book was written, I discovered that in 1999 the Museum of Scotland commissioned two American researchers, Dr Allen Simpson and Dr Sam Menefee of the University of Virginia, to examine the Arthur’s Seat coffins and formulate a solution. They concluded that the most likely explanation was that the coffins had been made by a shoemaker acquaintance of the murderers Burke and Hare, using a shoemaker’s knife and brass fittings adapted from shoe buckles, the idea being to give the victims some vestige of Christian burial, since a dissected

corpus

could not be resurrected.

The Falls

is, of course, a work of fiction, a flight of fancy. Dr Kennet Lovell exists only between its pages.

In June 1996, a man’s body was found near the summit of Ben Alder. He’d died of gunshot wounds. His name was Emmanuel Caillet, the son of a French merchant banker. What he was doing in Scotland was never ascertained. The report, produced from autopsy and scene-of-crime evidence, concluded that the young man had committed suicide. But there are enough discrepancies and unanswered questions to persuade his parents that this is not the real solution …

© Rankin

© RankinABOUT IAN RANKIN

Ian Rankin, OBE, writes a huge proportion of all the crime novels sold in the UK and has won numerous prizes, including in 2005 the Crime Writers’ Association Diamond Dagger. His work is available in over 30 languages, home sales of his books exceed one million copies a year, and several of the novels based around the character of Detective Inspector Rebus – his name meaning ‘enigmatic puzzle’ – have been successfully transferred to television.

Introduction to DI John Rebus

Introduction to DI John RebusThe first novels to feature Rebus, a flawed but resolutely humane detective, were not an overnight sensation, and success took time to arrive. But the wait became a period that allowed Ian Rankin to come of age as a writer, and to develop Rebus into a thoroughly believable, flesh-and-blood character straddling both industrial and post-industrial Scotland; a gritty yet perceptive man coping with his own demons. As Rebus struggled to keep his relationship with daughter Sammy alive following his divorce, and to cope with the imprisonment of brother Michael, while all the time trying to strike a blow for morality against a fearsome array of sinners (some justified and some not), readers began to respond in their droves. Fans admired Ian Rankin’s re-creation of a picture-postcard Edinburgh with a vicious tooth-and-claw underbelly just a heartbeat away, his believable but at the same time complex plots and, best of all, Rebus as a conflicted man trying always to solve the unsolvable, and to do the right thing.

As the series progressed, Ian Rankin refused to shy away from contentious issues such as corruption in high places, paedophilia and illegal immigration, combining his unique seal of tight plotting with a bleak realism, leavened with brooding humour.

In Rebus the reader is presented with a rich and constantly evolving portrait of a complex and troubled man, irrevocably tinged with the sense of being an outsider and, potentially, unable to escape being a ‘justified sinner’ himself. Rebus’s life is intricately related to his Scottish environs too, enriched by Ian Rankin’s attentive depiction of locations, and careful regard to Rebus’s favourite music, watering holes and books, as well as his often fraught relationships with colleagues and family. And so, alongside Rebus, the reader is taken on an often painful, sometimes hellish journey to the depths of human nature, always rooted in the minutiae of a very recognisable Scottish life.

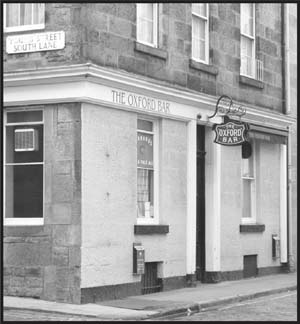

The Oxford Bar – Rebus and many of the characters who appear in the novels are regulars of the Ox – as is Ian Rankin himself. The pub is now synonymous with the Rebus novels to the extent that one of the regular medical examiners called in to assist with investigations is named after the pub’s owner, John Gates.

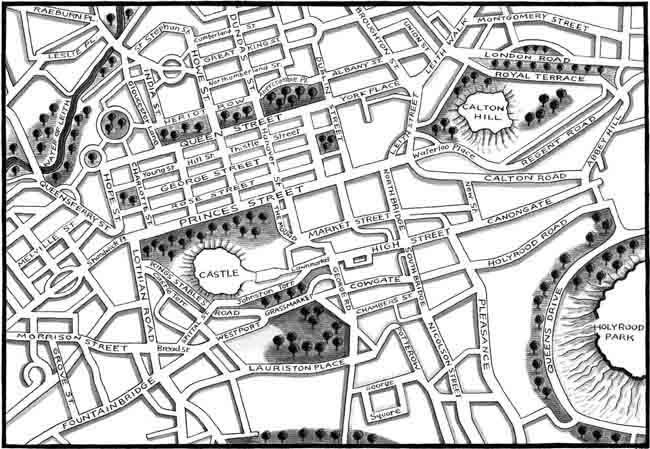

Edinburgh plays an important role throughout the Rebus novels; a character itself, as brooding and as volatile as Rebus. The Edinburgh depicted in the novels is far short of the beautiful city that tourists in their thousands flood to visit. Hidden behind the historic buildings and elegant façades is the world that Rebus inhabits.

regarding the Rebus series

How does Ian Rankin reveal himself as an author interested in using fiction to ‘tell the truths the real world can’t’?

There are similarities between the lives of the author and his protagonist – for instance, both Ian Rankin and Rebus were born in Fife, lost their mothers at an early age, have children with physical problems – so is it useful therefore to think of John Rebus and Ian Rankin as each other’s alter egos?