The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 (71 page)

Read The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General

Between 7 p.m. and 8 p.m. that evening, the Archbishop, much weakened by illness, was led out into an alley within the prison. With him was the ex-Empress Eugénie’s seventy-five-year-old confessor, Abbé Deguerry, Judge Bonjean, and three Jesuits. The Archbishop evidently showed great courage and dignity, giving each of the other five hostages in turn his benediction. The National Guards’ aim was as inaccurate as ever, and after the first volley the Archbishop remained standing. A teenager in the firing-squad called Lolive was heard to cry out ‘

Nom de Dieu

, he must be wearing armour!’, and the rifles crashed out again. This time Monseigneur Darboy fell, the second Archbishop of Paris to be shot down in a period of revolution during the nineteenth century.

1

As a crude form of

coup de grâce

, the National Guards ripped open the Archbishop’s body with their bayonets, then carried it off to be thrown into an open ditch at the Pére-Lachaise cemetery.

At 11 o’clock that night, word was brought to Delescluze of the death of the Archbishop. According to Lissagaray, the old Jacobin ‘listened without ceasing to write…. When the officers had left, Delescluze turned towards the colleague who was working with him and, burying his face in his hands, said: “What a war! What a war!”’

The Last Barricade

26. ‘Let us kill no more’

F

ROM

the execution of the Archbishop, one important figure had been conspicuously absent—Raoul Rigault. That day, exchanging his civil garb as Public Prosecutor for the uniform of a National Guard major, he had gone off to help direct the fighting in his old hunting-grounds of the Latin Quarter. In the afternoon of the 24th, Cissey’s corps had broken through and it looked as if the whole Panthéon district on the Left Bank would shortly fall. At about 3 p.m. Rigault withdrew to seek refuge in a hotel on the Rue Gay-Lussac where he kept lodgings, which he shared with an actress, under an assumed name. It was not long before the street was reached by Versailles troops, and they appear to have been informed that a National Guard major had been seen slipping into the hotel. Rigault’s landlord was dragged out and threatened with instant death. On the entreaties of the hotelier’s wife, Rigault intervened to save him, revealing his own identity. He was seized, so it was said, shouting ‘

Vive la Commune!

’; a regular sergeant then shot him several times through the head. For two days the

Procureur’s

body lay in the gutter, partly stripped by women of the

district, kicked and spat upon by passers-by, until one of his mistresses came to throw a coat over it.

For the best part of two terrible days Varlin and Lisbonne had put up a spirited defence based on Montparnasse’s Rue Vavin, against enormous odds. By midday on the 24th, it was clear they could hold out no longer. They now fell back, blowing up behind them the huge powder magazine at the Luxembourg Gardens. The

Versaillais

followed closely on their tracks, shooting batches of surrendered Communards as they went. At Varlin’s rear there were just three barricades protecting the strategic Panthéon heights, and no longer any organized reserves. By evening Cissey’s troops had captured the Panthéon and cleared most of the Boulevard St.-Michel. Varlin escaped, still fighting. On the Left Bank the struggle had all but come to an end. The sole exception was out on the extreme left flank where Wroblewski, though isolated from the rest of the Commune forces, was still keeping up a tough and professional defence from a stronghold atop the hill of the Butte-aux-Cailles, near the Porte d’Italie. He was supported by fire from the forts of Ivry and Bicêtre which—in disobedience of orders from Delescluze—he had stubbornly refused to evacuate.

During the 24th, MacMahon’s forces on the Right Bank had captured the Gare du Nord, the Porte St.-Denis, the Conservatoire, the Bank, and the Bourse. At the Bank they were greeted with more than enthusiasm by the Marquis de Plœuc and his four hundred employees, who during the last hours had been holding the buildings more or less in a state of siege. Rescue had not come a minute too early, for there had been serious talk of removing the Deputy Governor to add to the hostages held at La Roquette. The building itself was undamaged, as was the nearby Bibliothèque Nationale, which the retreating Communards had fortunately not had time to burn. In the markets of Les Halles, a bitter fight had gone on around the Church of St.-Eustache, converted into a Red Club, which the Communards had fortified with cannon and

mitrailleuses

. The way was now open to the Hôtel de Ville, the red-hot ruins of which were occupied at 9 p.m. that night. Delescluze, the remnants of the Committee of Public Safety, and the Comité Central all converged on the Mairie of the 11th

Arrondissement

, half-way up the Boulevard Voltaire, which became the temporary seat of the Commune. There Delescluze addressed the survivors, in a voice little stronger than a whisper: ‘I propose that the members of the Commune, wearing their sashes, should parade all the battalions that can be mustered, on the Boulevard Voltaire. We can then lead them to the points that have to be reconquered.’

M

AP

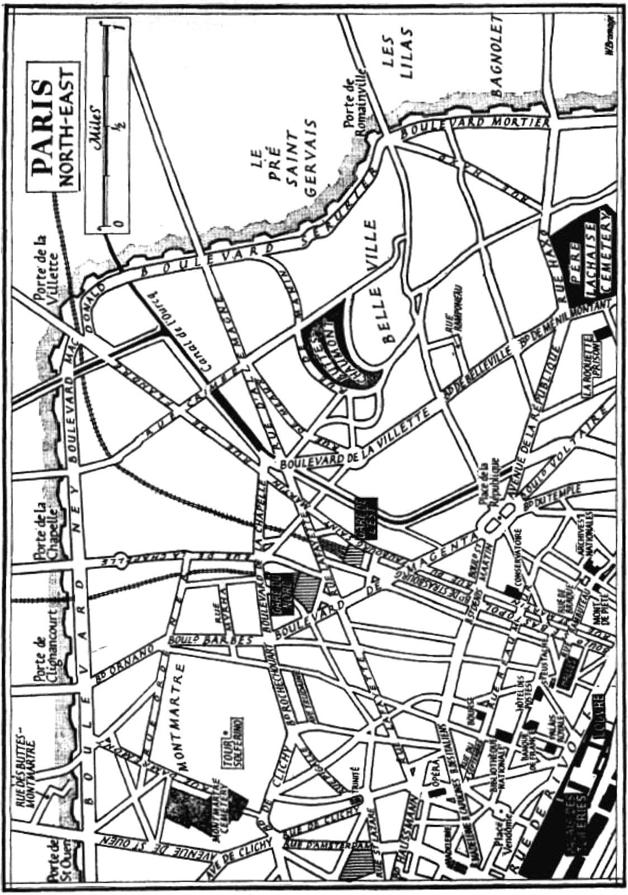

5. Paris: north-east

Only the eastern part of Paris still remained in the hands of the Commune; but it would henceforth be fighting on home ground, surrounded by a sympathetic population. Elsewhere, in the parts of Paris already captured by the Government troops, Colonel Stanley was astounded to note the first little signs of life returning to normal; outside his hotel in the Rue de la Paix an ‘active Frenchwoman had swept the pavement and door clear of rubbish’. That same day he was taken to see Pyat’s house, where he found only the sabre and greatcoat of the vanished leader.

On Thursday the 25th, the fourth day of operations in Paris, MacMahon’s plans were for Cissey to attack the Butte-aux-Cailles; Vinoy the Bastille; Clinchant and Douay the Château d’Eau area near the Gare de 1’Est.

1

With the 101st Battalion, which had proved itself probably the Commune’s most impressive fighting unit, Wroblewski was still holding the Butte-aux-Cailles, despite fresh orders from Delescluze to fall back on the 11th

Arrondissement

. One by one the supporting forts had fallen or been abandoned, the survivors of their garrisons trickling back to join Wroblewski on his hilltop. From dawn Cissey began hammering away at the narrow perimeter with a powerful concentration of fifty cannon. All morning the bombardment continued. Still Wroblewski held out; there was something about his stand that evokes the suicidal courage of the Warsaw uprising of 1944. Realizing by mid-afternoon that the enemy pincers were about to close behind him, he decided to carry out a fighting withdrawal through the Left Bank and across the river. As the remnants of the 101st pulled out, another tragic and senseless crime took place, for which it seems Wroblewski could probably not be held directly responsible. At Battalion H.Q. were held a score of Dominican monks, arrested by Rigault during his round-up of the priests. An officer now came to tell them that they were free to go, but as the bemused monks walked out of the building, they were shot down, one after the other, by some National Guardsmen, enraged at the summary execution of their comrades who had surrendered.

Miraculously Wroblewski reached the Pont d’Austerlitz, nearly a mile and a half away, and crossed into safe territory. With the handful of survivors that remained to him, he reported to Delescluze at the Mairie of the 11th. Delescluze offered him the over-all command of what remained of the Commune forces. ‘Have you got several thousand resolute men?’ inquired Wroblewski. Delescluze, having that morning inspected the troops in hand, replied ‘at most several hundred’. Wroblewski decided he could not accept the responsibility of command in these conditions, and demanded to be allowed to

fight on as ‘a simple soldier’. Picking up a rifle he disappeared towards the barricades.

One by one the leaders of the Commune were falling. From the barricades defending the Bastille, a wounded Frankel came back supported by Elizabeth Dimitrieff, herself wounded. Lisbonne fell with a bad wound, later resulting in an amputation. ‘Burner’ Brunel, who had continued to fight tenaciously ever since his stand at the Concorde and was now covering the Château d’Eau district at the head of a ‘Youth Battalion’, was crippled by a bullet through the thigh. Loyally his young boys bore him off to a place of safety at the rear. All that day Delescluze, looking more than ever like a man under imminent sentence of death, had hurried from barricade to barricade, supervising, encouraging, exhorting. But with the overwhelming pressure that the vastly superior Versailles forces were now bringing to bear he knew that it was only a question of time before any pretence of a co-ordinated defence came to an end, and the Communards were split up into isolated packets. He sat down to write a last letter to his sister;

Ma bonne soeur

I do not wish, and am unable, to act as the victim and the toy of a victorious reaction. Forgive me for departing before you, you who have sacrificed your life for me. But I no longer feel I possess the courage to submit to another defeat, after so many others. I embrace you a thousand times with all my love. Your memory will be the last that will visit my thoughts before going to rest…. Adieu, adieu….

Shortly before 7 p.m. that evening, Lissagaray saw Delescluze—dressed as always like an 1848 revolutionary in a top hat, lovingly polished boots, black trousers, and frock coat, a red sash around his waist, and leaning heavily on a cane—move off towards the Château d’Eau with some fifty men. Just before reaching the barricade across the Boulevard Voltaire, Delescluze met Pyat’s old enemy, Vermorel, who had been mortally wounded. After gripping his hand and saying a few words of farewell, Delescluze walked on alone to the already abandoned barricade, some fifty yards further on. Before the eyes of Lissagaray and the detachment he had brought with him Delescluze slowly, painfully clambered up on top of the barricade. He stood there for a moment, silhouetted in the sinking sun; then pitched forward on his face. Four men rushed to pick him up; three of them were shot down too. In the moment of defeat, the old Jacobin had achieved a certain nobility denied to either Louis-Napoleon at Sedan, or Ducrot at the Great Sortie.

The Commune was now leaderless. Under cover of night it abandoned most of the Bastille area and the present Place de la République (then Château d’Eau), retreating back into the womb from which it had sprung—the narrow streets and squalid slums of Belleville. Behind it the Seine still gleamed red with the reflection of burning Paris. After nearly four days of card-playing incarceration with his friends, the Johnsons, Edwin Child had at last been liberated in the Rue Rambuteau. Throughout the previous day they had heard a ‘terrible din that never ceased for an instant, not knowing at what moment our own time might arrive’. His grammar deserting him in the heat of the moment, he recorded that on the night preceding the 25th he

did not dare slept upstairs, bombs having fallen upon nearly every house in the

voisinage

. Fortunately part of the

maison

was occupied by a dealer in skins who kindly offered us

asile

(10 women 5 men). Slept upon bearskins almost as well as in my bed, much to the astonishment of the others who could not close their eyes for the sinister whistling of the bombs. Lovely day.

On being liberated the following afternoon, Child’s first thought was to discover whether his shop and his lodging, were still safe:

… but had not gone far before I was stopped to work at the pumps, and what a sight met my eyes; destruction everywhere. From the Châtelet to Hôtel de Ville, all was destroyed, not a room left; worked about half an hour, then proceeded on my way. Saw three waggons of dead Communists [

sic

] taken out of

one

yard….