The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 (65 page)

Read The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General

C’est la canaille,

Eh! bien, j’en suis!

1

The members of this essentially proletarian audience, for whose delectation tables groaning with brioches and beer had been laid out in the former banqueting hall, were ‘not very orderly in their behaviour’, the

Illustrated London News

complained; while Colonel Stanley sniffed fastidiously that ‘the stink became so bad I could not stay it out’. But for the organizers the distraction was a huge success, and it was repeated on the 14th and the 18th.

With the Tuilerie concerts, an extraordinary kind of exaltation, almost of valedictory gaiety, seemed to seize the supporters of the Commune as the final catastrophe became more obviously imminent. Once again the boulevards filled; this time with strangers from the darker parts of Paris. It almost seemed as if they had come out to enjoy for the last time the opulence and grandeur of those foreign parts of the city which they loved with such possessive, destructive pride. Spring was at its splendid peak, and on the Concorde Communards replaced the withered laurels garlanding the statue of Strasbourg with offerings of flowers. To many it seemed as if there had never been quite so many flowers as that spring. ‘In the young verdure and the bloom of vernal shrubs’, Goncourt lyrically observed some National Guards ‘lying alongside their arms which glistened in the sunshine, with a blonde

cantinière

pouring out a drink for a soldier with her Parisian grace.’ But he could not avert his eyes from the unpleasant reminders of war inseparably mingled with this idyllic scene; ‘a corpse being hoisted on to a cart, of which a man

holds in his two hands the brain ready to escape from its open skull’. On Sunday, May 14th, Goncourt’s raptures were less marred; ‘All that still remains of the Paris population is at the bottom of the Champs-Élysées, under the first trees, where the gaily clamorous laughter of children seated in front of the Punch and Judy shows occasionally rises above the voice of the distant cannonade.’ That same day Dr. Powell observed that the

Parisians were out in their Sunday best, usually morning attire, watching with interest the erection of formidable earth works at the top of the Rue de Rivoli and Rue Royale, the guns of which were to sweep the Place de la Concorde of the entry of the troops; the fountains were playing as usual, the water hoses being plied, whilst at the barricades a roaring trade was being driven in

sirop de vanille

, in the horrid periodical

Le Père Duchesne

, and in coarse illustrated skits on Napoleon, Eugénie, Thiers… and away towards the ramparts again might be seen a kite high in the air….

The next Sunday evening, May 21st, the Commune threw its most ambitious entertainment yet in the form of a vast open-air concert in the Tuileries Gardens, at which fifteen hundred musicians took part. ‘Mozart, Meyerbeer’, claimed Lissagaray, ‘and the great classics chased out the musical obscenities of the Empire’. Again it was a huge success. At the end, amidst heavy applause, a Communard staff officer mounted the conductor’s stand with a brief announcement: ‘Citizens, Monsieur Thiers promised to enter Paris yesterday. Monsieur Thiers did not enter; he will not enter. Therefore I invite you here next Sunday, here at this same place….’

But at that identical moment the troops of Monsieur Thiers were beginning to pour into the city.

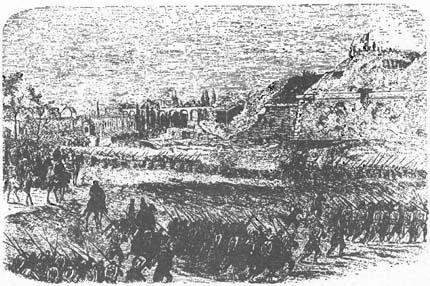

Versailles Troops Enter Paris

24. ‘La Semaine Sanglante’—I

U

P

to the very last minute, Clemenceau, his fellow Mayors, the Deputies of Paris (jointly united as the ‘League of Republican Union for the Rights of Paris’), and various other bodies had still been seeking anxiously to achieve a negotiated compromise between Paris and Versailles, before the disastrous final confrontation took place. At the end of April the Freemasons of Paris had massed together, and, in top hats, bearing their Masonic orders and banners, bravely mounted the ramparts to demand a parley with the

Versaillais

. A deputation had been received, but to them—as to all others—Thiers replied with his unwavering formula: ‘Do you come in the name of the Commune? If so, I shall not listen to you; I do not recognize belligerents…. I have no conditions to accept, nor commitments to offer. The supremacy of the law will be re-established absolutely…. Paris will be submitted to the authority of the State just like any hamlet of a hundred inhabitants.’ He did not intend, and never had intended, that there should be any compromise with the rebellious city. Now that he had the power he proposed to crush the Commune mercilessly. But when, following the fall of Fort Issy, he

began what he described as the ‘orthodox and classic methods of siege’, sapping his way forward across the Bois de Boulogne, his slow and methodical preparations received a nasty holt. Bismarck, growing as impatient as he had with Moltke during the first Siege, threatened Thiers that if he did not hurry up, the Prussian Army would itself enter Paris.

This would have been a political disaster of the first magnitude, and, as Thiers admitted, ‘it was why we had now also thought of purchasing the entry of one of the gates to Paris’. Several attempts to open a way into the city by ‘Fifth Column’ work had failed, but one plan proposed by ‘a very brave man who entered and left Paris every day’ seemed to promise success. On the night of May 13th no less than 80,000 men stood by, concealed in the Bois de Boulogne, waiting for this modern Ulysses to lead them through the city gates. Thiers himself was there. But by 4 a.m. nothing had happened and the Army withdrew, disappointed. From now on Thiers spent every day at the front, full of Micawberish hopes. Still there was no sign of a breach in the walls, or the opening of a gate, so resignedly Thiers convened a Council of War at Mont-Valérien on Sunday, May 21st, to fix a date for the postponed general assault on the walls of Paris. He had reached the entrance to the fortress, when an excited staff officer galloped up to inform him that General Douay could not now attend the conference as he was occupied in entering Paris. Thiers hastened inside, where he found Marshal MacMahon studying the movements of Douay’s troops through a spyglass. At first it looked as if they had been repelled, then—after about a quarter of an hour—Thiers saw ‘two long black serpents, winding through folds in the ground, head towards the Point-du-Jour Gate, by which they entered’.

It had happened as follows. At Montretout, one of the objectives of Trochu’s final sortie in January, the

Versaillais

had established what Wickham Hoffman (with memories of fighting at the Siege of Vicksburg under Ulysses Grant) described as ‘probably the most powerful battery ever erected in the world’. This may have been a slight exaggeration; nevertheless, for several days it had pounded the Point-du-Jour area to such an extent that the ramparts had been partly demolished and the defenders had withdrawn some distance from the devastated area. On Sunday, May 21st, a civil engineer named Ducatel, an overseer in the Department of Roads and Bridges who felt no love for the Commune, happened to stroll near the battlements on his afternoon walk. He was astonished to perceive that near the Point-du-Jour there was not a defender in sight. After a brief reconnaissance, he discovered that no one was holding the gate

there. (Why MacMahon’s troops had not become aware of this, Colonel Hoffman claimed, could ‘only be accounted for by the general inefficiency into which the French Army had fallen’.) Ducatel now mounted the ramparts, waving a white flag. A Versailles major came forward; Ducatel told his story; this was verified; and Douay’s troops began to pour into Paris through the undefended gate. After all that had passed since the previous September, it was—as Hoffman remarked—‘rather an anti-climax’.

Thiers now returned to Versailles to dine ‘with my family and a few friends who shared my joy’.

At the Hôtel de Ville, the Commune had been busy formulating its last legislation. Apart from an order sending some staff officers, who had been caught philandering with

cocottes

, to the front with picks and shovels (the girls to a sandbag factory), in the four previous days there had been a Decree of Legitimacy, a new decision on the Secularization of Education, and a Decree on the theatres. Now the Assembly was in the midst of trying Cluseret for dereliction of duty. Suddenly, at about 7 o’clock that Sunday evening, Billioray, one of the members of the Committee of Public Safety, burst in shouting. ‘Stop! Stop!’, he cried, ‘I have a communication of the utmost importance, for which I demand a secret session.’ The doors were closed and Billioray read out a dispatch from Dombrowski reporting the Versailles entry. There was, according to Lissagaray, ‘a stupefied silence’, then uproar. Rigault, supported by Ferré, his successor as police chief, recommended that the Commune forces should blow up the Seine bridges and withdraw into the old Cité area for a last-ditch defence, burning all behind them. He also proposed that the hostages should be brought along too, ‘and they will perish there with us’. Cluseret was released, and an hour later the Commune adjourned; the last time that it would ever hold a plenary session at the Hôtel de Ville.

Delescluze at the Ministry of War heard the news grimly, but with calm, and ordered Assi, the incompetent first Chairman of the Commune, off on reconnaissance of the threatened area. The haggard old Jacobin then dictated a street-by-street defence of the city, placing Brunel, who—once again in disfavour—had only been released from a spell in prison the previous night, in command of the key position around the Place de la Concorde. He completed his night’s work with the issue of a rousing proclamation to the Citizens of Paris:

Enough of militarism! No more General Staffs with badges of rank and gold braid at every seam! Make way for the people, for the fighters with bare arms! The hour of revolutionary warfare has struck!

It was a call to the barricades, and the old appeal for the spontaneous, unorganized, torrential

levée en masse

heard so often from Delescluze and the Reds during the first Siege. But although for some days past 1,500 women had been set to work sewing sandbag sacks in the disused National Assembly building, at 8 centimes a sack, none of the second line of barricades recommended by Rossel had yet been completed. And now there would be no coherent plan of defence either. The barricades as prescribed by Delescluze were tactically more suited for guarding districts than for any integrated defence of the whole city. Rossel with his engineer’s eye understood precisely the military significance of the obliquely intersecting streets of Haussmann’s Paris, but his frequent warnings of how easy Haussmann had made it for regular troops to ‘turn’ a barricade went unheeded by the Jacobins with their memories of ’48. At 5 a.m., leaving all his papers undestroyed, Delescluze abandoned his office for the barricades.

Outside the turbulent chambers of the Commune, Paris had spent the rest of that sparkling May Sunday in joyous oblivion. The city, thought the Rev. Gibson, ‘seemed to be

en fête

. There have never been such crowds all around the Place de la Concorde except on some extraordinary occasion, such as the fete of the 15th of August under Imperialist rule, and everybody appeared to be in holiday dress.’ In his diary, Edwin Child entered this account of his day:

Up at 8. Church at 11. At 1 o’clock met Madame Clerc (rendezvous) at the Madeleine, breakfasted

au

Café du Helder… afterwards strolled to Champs Elysées. There rested best part of afternoon. About 5 p.m. saw her home (Avenue Friedland), walked to my room, had tea, and then took bus to Johnson’s, where I passed the evening. Lovely day.

As darkness fell, life continued. At the Gymnase there was a gala première of

Les Femmes Terribles

and the theatres had never been fuller. Pompeii on the night before its extinction can hardly have been gayer. At his ‘usual place of observation’, Goncourt, who had evacuated his house in the hazardous neighbourhood of Auteuil to lodge temporarily in the centre of Paris, saw a man arrested for shouting that the

Versaillais

had entered.

I wandered around for a long time in search of information…. Nothing, nothing at all…. Another rumour. Finally I returned home. I went to bed in despair. I could not sleep. Through my hermetically closed curtains I seemed to be able to hear a confused murmur in the distance. In a street some way off there was the usual noise of one company relieving another, as happened every night. I told myself I had been imagining things and went back to bed… but this time there was no

mistaking the sound of drum and bugle! I rushed back to the window. The call to arms was sounding all over Paris, and soon, drowning the noise of the drums and the bugles and the shouting and the cries of ‘To Arms!’ came the great, tragic, booming notes of the tocsin being rung in all the churches—a sinister sound which filled me with joy and sounded the death-knell of the odious tyranny oppressing Paris.