The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 (39 page)

Read The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General

One after another, he had fallen out with his generals after they disappointed him. Aurelle had been sacked and submitted to vituperation in which his conduct was approximated to Bazaine’s, and under such accusations of treachery more than one general preferred to relinquish his command. There was no escaping the fact that by January all Gambetta’s armies in the field which might have relieved Paris had failed. Chanzy, for all the remarkable spirit that he still managed to instil into the Army of the Loire, had been pushed back to Le Mans and largely neutralized. Faidherbe, though performing wonders in the north in Flanders and Artois until he was brought to bay at St.-Quentin, clearly had no hope now of breaking through to join Trochu. It was little wonder that Gambetta was reported to be looking old and depressed. But true to his character he still refused to abandon hope, and there remained to him one trick comprising two rather dog-eared cards.

While Louis-Napoleon was still on the throne, that great Italian champion of liberal causes and the downtrodden, Giuseppe Garibaldi, had actually contemplated launching his volunteers into an invasion of France. But when the new Republic was proclaimed and France

became the underdog, his sympathies performed a rapid turnabout. On October 7th, accompanied by his sons, Ricciotti and Menotti, and collecting several thousand troops as he went, the leonine old warrior landed in Marseilles; his fingers bent with rheumatism, his legs so lame from past wounds that at times he had to be carried in a litter, but he was still indomitable. In Tours, Crémieux greeted the news with ‘My God—we needed only

that!

’ and the Garibaldians were assigned an unimportant role in the south-east of France, to keep them out of mischief. This Garibaldi quickly turned to good advantage. On November 19th, Ricciotti and 560 men (plus one of the ubiquitous

Daily News

correspondents) attacked the German garrison at Châtillon on the upper reaches of the Seine (not to be confused with the Châtillon on the southern fringe of Paris), some 120 miles south-east of Paris. The Germans there numbered nearly a thousand, but Ricciotti succeeded in capturing 167 of them as well as much booty, and in killing the colonel in command. Ricciotti then withdrew, with a loss of only three killed and twelve wounded. This brilliant

coup de main

threw the local German forces into great anxiety, the ripples of which reached Versailles; for Châtillon was but sixty crow’s-flight miles away from the Prussians’ single supply-line to Paris. As the Crown Prince gloomily predicted: ‘Should the Garibaldians succeed in falling on Vitry-le-François or any other point of our railway lines, they would be in a position to cut off for the moment all our communications with the frontier and home.’ A week after Châtillon, less successfully, Garibaldi risked a pitched battle in attempting to retake Dijon, and narrowly escaped disaster at the hands of General von Werder. But Garibaldi’s exploits had belatedly kindled a bright vision in the mind of that amateur strategist, Gambetta.

In mid-December, but not until mid-December, Gambetta decided to expedite Bourbaki, the last of his generals, with an army one hundred thousand strong, to join up with Garibaldi and raise the Siege of Paris by severing Prussian communications through a right hook aimed at Lorraine. The choice could hardly have been less fortunate; had it been Chanzy or Faidherbe the prospects might have been much better. But Bourbaki the dapper Guardsman, object of that merry jingle of Empire days,

1

was still Imperialist at heart, as unenthusiastic about Gambetta and the Republic as he was about continuing the war itself. In turn his civil superiors lacked confidence in him, and indeed he had little confidence left in himself; as he

grumbled to one of his young officers who had proposed a night operation, ‘I’m twenty years too old. Generals should be your age.’ Transporting Bourbaki’s army to the south-east proved too great a strain for Freycinet’s railways, and in the arctic weather the troops suffered appallingly. When they reached the Dijon area, ill fed and ill clad, their fighting value was sharply diminished. There was much confusion in liaising with Garibaldi, combined with inept staff-work and an uninspiring example set by Bourbaki; and climatic conditions were such that only a Russian army could have attacked with vigour. Yet, despite all this, under the new threat von Werder was forced temporarily to evacuate the important centre of Dijon, causing once again gravest alarums at Versailles. As late as January 14th, the Crown Prince was offering fervent prayers: ‘We trust to heaven that, in his extraordinarily strong defensive position, he will succeed in holding back General Bourbaki’.

But it was altogether too late. Secretary Wickham Hoffman of the U.S. Legation in Paris who had served as a colonel under General Grant at the Siege of Vicksburg was one American Civil War veteran who was astounded that ‘no serious effort was ever made to cut the German lines of communication’. He later recalled how General Sheridan, the Unionist Cavalry leader, had exclaimed to him—depite his pro-German sympathies, and using a word reminiscent of the

mot de Cambronne

—that if he ‘had been outside with thirty thousand cavalry, he would have made the King * * * *’. Sheridan in fact had the lowest opinion of the employment of cavalry by both sides in the Franco-Prussian War, and had Gambetta possessed the services of a Jeb Stuart, or even of Sheridan himself—let alone of a Robert E. Lee—the outcome of the Siege and indeed the whole war might well have been different. Certainly, that a serious initiative against Moltke’s communications was not contemplated much earlier must be rated one of the worst strategical errors of the Tours Government. The Prussian commander dispatched to repair the damage done by Bourbaki, General von Manteuffel, himself admitted that the Garibaldi-Bourbaki campaign might well have been, for the French, ‘the most fortunate of the war of 1870–71’. As it was, it was to provide the final French catastrophe of that war.

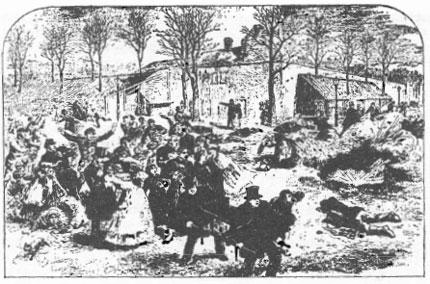

Prussian shells fall in Montparnasse

14. Paris Bombarded

O

N

the cold morning of December 27th, a French colonel called Heintzler and his wife were giving a breakfast party for several friends at the recently acquired outpost of Avron. Suddenly the party was spoiled by a heavy Prussian shell which burst without warning in the room. Six of the breakfasters were killed outright, the host and hostess were gravely wounded, and only the regimental doctor and a servant emerged unscathed. Two days later Felix Whitehurst recorded seeing the remains of the six victims in his hospital: ‘but it was such a human ruin that no individuality could be recognised’. Ceaselessly during those two days Prussian guns of a calibre hitherto unknown continued to plunge their huge shells down on Avron. A grim new phase of the Siege had opened.

The Avron plateau was a magnificent natural feature due east of Paris, with commanding views on all sides. But it lay beyond the line of French forts, like an island, isolated from Fort Rosny by a deep and wide ravine. It had been seized by the French to support Ducrot’s Great Sortie, and should logically have been abandoned when the Sortie failed, but it was the kind of textbook position that

military men are habitually reluctant to give up. Despite the fact that the artillery was commanded by Colonel Stoffel, the enlightened former Military Attaché in Berlin who had done his best to warn France what to expect of Moltke’s army, little had been done during the four weeks of French tenancy to organize Avron’s defences. Beyond the usual half-heartedness and procrastination, there was the sheer incapacity of undernourished men to dig in the frozen earth. Entrenchments had been prepared to withstand little more than field-artillery fire. As O’Shea remarked, ‘

the earth had hardly been stirred

’. Forbes, who on the other side of the lines was watching the Saxons vigorously felling trees as they brought up their huge guns, was amazed that the French should remain apparently deaf, and blind, to all the fracas of these preparations. To bombard this one small position, Moltke had brought up seventy-six of his heaviest guns: Krupp steel 24-pounders which in fact threw 56-lb. projectiles, and even bigger Krupp pieces that could fling a shell of 110 lb. Later, an observer told O’Shea in awe how he had seen one crater thrown up at Avron by the Krupp guns measuring four and a half feet across and a yard deep; not much by twentieth-century standards, but a record for those days. The shallow French entrenchments were swiftly shattered; young troops unnerved by this hideous new experience ran screaming to the rear; and one after another Colonel Stoffel’s gun positions were silenced. All day the searing bombardment continued. The next day the German gunners re-sighted their pieces, and the shelling was resumed with even more lethal accuracy. Trochu came out to survey the scene, as did Tommy Bowles, and both displayed their customary courage under fire. But by the 29th the French were left with no alternative but to evacuate the whole plateau.

After the forty-eight-hour German bombardment, the Avron plateau presented a forlorn picture. Even the battle-hardened Forbes who visited it in the wake of the Saxons was appalled:

No man who long followed this war but must have become so familiar with the aspect of slain men, that the original thrill and turn of the blood at the sight had faded into a memory of the past, at which he all but smiled when it dimly recurred to him; but the terrible ghastliness of those dead transcended anything I had ever seen, or even dreamt of, in the shuddering nightmare after my first battle-field. Remember how they had been slain. Not with the nimble bullet of the needle-gun, that drills a minute hole through a man and leaves him undisfigured, unless it has chanced to strike his face; not with the sharp stab of the bayonet, but slaughtered with missiles of terrible weight, shattered into fragments by explosions of many pounds of powder, mangled and torn by massive fragments of iron.

It was a reaction more or less novel to war correspondents—until 1914, and before familiarity with mutilation bred insensibility.

On the other side, O’Shea was staggered how Avron had been ‘literally shaven’ by the huge projectiles; but at the same time he noted shrewdly that ‘their very dimensions militated against their destructiveness in instances, as they penetrated to such a depth that their large splinters at bursting lodged in the ground, harmlessly displacing the clay’. And in fact the German shells, filled only with black powder (since T.N.T. was yet to be invented), caused less than a hundred casualties. It was their moral, rather than their physical effect, that drove the French off Avron. But the German success was sufficient to have a telling influence upon both sides. In Paris, morale suffered a serious setback at this first unequivocal sign that the enemy’s offensive potential might be stronger than the Paris defences. The cannonade, heard all too plainly in the centre of the city, sounded a deadly harbinger in Parisian minds of what lay in store for themselves. Wrote Washburne: ‘The Parisians are “low down” today, and I think Trochu is going down. But he is as hard to get rid of as some of the officers we had during the time of the Rebellion.’ At Versailles Avron was regarded as a ‘dummy run’ that had exceeded all hopes. Even the Crown Prince was forced to admit ‘we have enjoyed a fine success we never expected’, and his principal supporter in the anti-bombardment camp, Blumenthal, declared that the ‘brilliant’ results at Avron had now persuaded him; ‘it is quite possible that the time has come when a bombardment of the forts and a portion of the city may be successful’. For, he concluded, it was apparent ‘the French are no longer making a serious stand’. On New Year’s Eve, after a long session, the King of Prussia gave the order for the bombardment of Paris to begin as soon as possible. It was an act fertilizing the ovum of a new monster and a new myth that would long affront and appal world opinion, under the name of ‘Teutonic frightfulness’. The Crown Prince wrote in his diary: ‘May we not have to repent our folly….!’

In order that the heavy guns could bombard the city unmolested from close-in positions, the southern forts had first of all to be silenced. From Fort Issy, a French corporal of the

Mobiles

wrote to his father on New Year’s Day ‘… in short, life is tolerable; but alas I have an idea that I shall not long enjoy this relative well-being… there is bombardment in the air.’ Vigorously the garrisons were set to work filling sandbags and carrying out other last-minute preparations on the defences. On January 5th, the same corporal was again writing to his father: ‘At 8 o’clock he [a fellow soldier] had just opened one of our windows looking out on to Châtillon, to empty a

certain mess-tin

from which one does not eat

, when a shell, passing over his head, traversed our barrack room to explode I don’t know where…. In a flash, everybody was at the bottom of his bed, leaping into his boots.’ Within a short time Prussian 220-mm. guns firing from the dominating Châtillon heights (wrenched from Ducrot in September) had smashed most of the gun embrasures, turned the interior court into a zone of death, and rendered uninhabitable the barracks that faced outwards. Supplementing the heavy guns the Prussians also employed a weapon the French gunners disliked even more: low-trajectory ‘rampart guns’ firing a 20-mm. projectile that could penetrate ramparts and kill at 1,300 yards, and thereby make repair work on the defences extremely unpleasant. By 2 p.m. on the same day, the guns of Issy had been silenced; as the French were to discover again in 1914, their fortifications were simply not adequate to face the latest products of Herr Krupp. The story was similar at Fort Vanves, where nine guns had been swiftly knocked out and urgent pleas for support addressed in vain to Forts Issy and Montrouge. Only Montrouge still replied with any vigour, but as Moltke later wrote, ‘the forts never again got the best of it’. Yet even to his shrewd gaze the long-term, material inefficacy of the huge shells of that day remained unrevealed, as indeed it had been during the success at Avron. Throughout the bombardment in which as many as 60,000 shells were rained down on it, Fort Vanves lost only 20 men killed out of its garrison of 1,730. Likewise, only 18 were killed and 80 wounded out of 1,900 in Issy. Although three out of four of Issy’s barracks were destroyed, the ramparts remained intact and in none of the forts was any breach made in the actual defences. These facts were not, however, apparent to Moltke; the demonstrative results at Issy and Vanves were that the Prussian siege batteries could now move forward as much as 750 yards nearer to the heart of Paris.