The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 (28 page)

Read The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General

On November 14th the news of Coulmiers was brought to Paris by a line-crosser, Ernest Moll, a farmer whom the Prussians had used as a guide. The city exploded in a delirium of joy. ‘We have passed from the lowest depths of despair to the wildest confidence’, exclaimed Labouchere. ‘I am so happy’, declared Juliette Lambert, ‘that I would willingly give myself up to arrogance. Yes, we have a success….’ Strangers kissed each other on the boulevard;

Le Figaro

saw the hand of God at work, and acclaimed Aurelle a modern Maid of Orléans. In the excitement, the revolt of October 31st and the growing food shortage were forgotten. At long last the spell of defeats had been broken!

At the Louvre, however, once the initial excitement had subsided, the Government was far from sharing the exultation of the boulevards. Gambetta’s success struck at the heart of

le plan

, which had now gone far towards fruition. The whole weight of the Paris Army had already been shifted towards the north-west; immense preparations had been made, including the construction of pontoon bridges; and the sortie was scheduled to begin within the next week. To the non-military members of the Government with their simple civilian understanding of logistical problems, the solution was straightforward; ‘Cheer up,

mon cher général

’, was the cautious Picard’s immediate reaction, ‘here’s a stroke of good fortune which will perhaps save us from proceeding with our heroic folly’. If nothing else, public opinion, of which, since October 31st, the Government was increasingly mindful, and which was already ejaculating slogans of ‘

lls viennent à nous

;

allons à eux!

’

1

was forcing the Government’s hand. But Trochu, aware of the ponderous technical difficulties involved, hesitated. Then, on November 18th, a second message arrived from Gambetta, urging him to co-operate by striking southwards towards Orléans. This decided the Government. The next day Trochu told a shocked Ducrot that his offensive would now have to be transported lock, stock, and barrel to the other side of Paris. For the third time in two months, Ducrot fumed with, rage and frustration; as he put it his disappointment was ‘not less than his embarrassment’.

It was hardly an exaggeration to say, as Trochu did, that what Ducrot was now being asked to perform was ‘the most extraordinary

tour de force

of the Siege of Paris’. Through the Paris streets had to be shifted 400 guns, 54 pontoons, and 80,000 men with all their supplies and equipment.

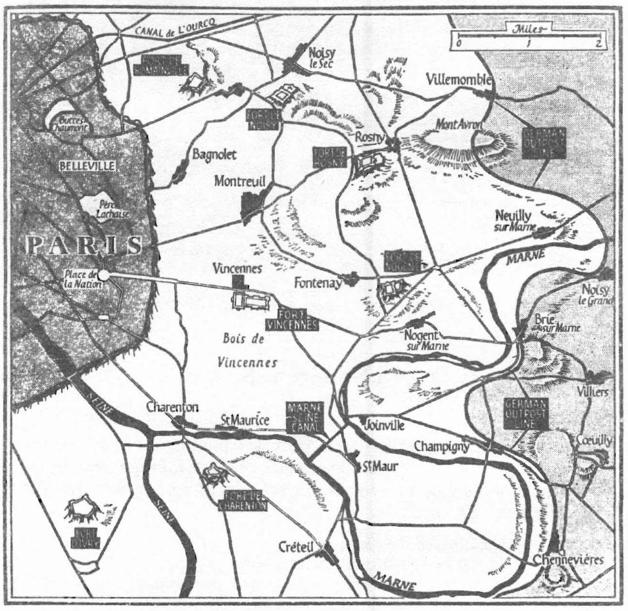

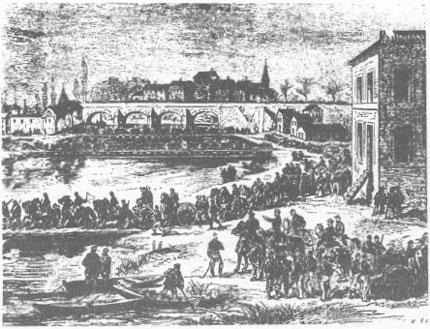

Worst of all, whereas Ducrot had selected the Gennevilliers peninsula in the first place because the enemy was relatively weak there, the route connecting with Gambetta’s advance from Orléans now lay across the famous Châtillon Plateau, wrested from Ducrot at the end of September, which had since become perhaps the strongest sector of the whole Prussian line. Quickly discarding this approach, Ducrot decided instead to mount his attack south-eastwards across the Marne, before its confluence with the Seine. Once he had broken through the ring, his intention was to swing westwards to meet up with Gambetta’s forces somewhere in the area of Fontainebleau. In contrast to the Basse-Seine project, however, his new line of advance lay through territory controlled by German Armies, and an attack across the Marne necessitated complicated bridging operations in the face of the enemy. With five weeks in which to prepare the previous offensive, there was, he claimed, only five days for the planning of this one; therefore certain omissions were inevitable.

With all the activity involved in transposing Ducrot’s Army, it was impossible that the enemy should not have learnt something of what was afoot. In any case, as has been demonstrated on other occasions in France’s military history, good security is not where her most formidable talents lie. Despite Trochu’s assertion that only five officers were in on the original plan, most of the British correspondents seem to have gleaned details of it, and by the beginning of November it was being freely discussed among Goncourt’s circle at their favourite dining place, Brébant’s, where derisive laughter met the suggestion that Trochu was planning to ‘lift the blockade of Paris within a fortnight’. As early as October 21st, when Ducrot was carrying out his preliminaries at Malmaison, the Crown Prince of Prussia noted in his diary admissions by French prisoners that ‘a sortie on the largest scale is being planned against Versailles and Saint-Denis, with the object of bringing into Paris a convoy of provisions from Rouen’; and as soon as Gambetta had begun to march on Orléans, even before the Battle of Coulmiers, the Crown Prince was predicting a major sortie out of Paris in that direction. On November 16th, while Trochu was still making up his mind, Moltke ordered the Third Army, as ‘a temporary measure’, to concentrate its forces on the left bank of the Seine south of Paris, showing that he was fully aware of the potential threat. By November 27th,

Bowles was reporting, ‘I have had confided to me nothing less than General Trochu’s famous plan, and have witnessed the preparations for its execution’; officers had even boasted to him ‘that in eight days we shall be in communication with the outside’. Also on this same day Jules Claretie noted the demolition of the barricades at Nogent-sur-Marne so that the artillery could pass; while, after dinner that evening, General von Blumenthal received a telegram warning that the French had thrown a bridge across the Marne near Joinville, opposite the Württemberg division. The next day orders were sent out to reinforce the division. Finally, on November 30th, Labouchere wrote that Ducrot’s new plan had been ‘confided to me by half a dozen persons, and, therefore, I very much question whether it is a secret to the enemy’.

Still dubious about Gambetta’s prospects, and perhaps (belatedly) also influenced by security considerations, Trochu had once again procrastinated before notifying Tours of the change in plan, and the date of the new sortie: November 29th. Not until the 24th, only five days before the attack, did he finally dispatch a message; and then it was prevented from reaching Gambetta in time by probably the most extraordinary mishap of the entire war. The balloon to which Trochu entrusted the crucial intelligence was called, appropriately enough, the

Ville d’Orléans

. The thirty-third to leave Paris, it carried a crew of two: Rolier, the pilot, and Béziers. Since Prussian anti-balloon measures had made daylight flights increasingly risky, the

Ville d’Orléans

took off from the Gare du Nord under cover of darkness, shortly before midnight. As dawn came up, the two men saw that a heavy fog obscured the earth. Lacking anything but the most primitive navigational instruments, they had not the faintest idea of their position, but—as they had set off in a propitiously moderate south-south-east breeze—comfortably assumed that they were heading towards unoccupied north-western France. In the utter stillness of the ether, Béziers thought he heard beneath them something like the sound of continuous railway trains. Then the fog rolled away, and to their horror the aeronauts realized that the noise was in fact waves. As Béziers noted down in his log: ‘The sea for us, that’s death!’ By mid-morning the

Ville d’Orléans

was still flying out over the sea. At last they sighted a number of ships; Rolier came down as low as he dared, and let out the 120-yard guide-rope in the hopes that a ship might be able to grab it. But, as the ships seemed quite oblivious to their cries and signals for help, they decided to seek the safety of greater heights by jettisoning ballast. Among the objects sacrificed to the waves was a 60-kilogramme bag of dispatches containing the vital message on which hung the fate of Paris.

The balloon rose into dense cloud, and once again the earth vanished out of sight. It became bitterly cold, and the two men’s moustaches turned to icicles. In noble devotion, Béziers took off his mantle to protect the carrier pigeons; though at this point it must have seemed that the prospects of survival for both birds and men were extremely low. On and on the balloon sailed. Then, just before 2.30 p.m., it began to descend rapidly. Out of the clouds the top of a pine tree suddenly emerged; a sight no less welcome than the coastline of Greenland must have been to the Vikings. It was too much for the half-frozen men who had begun to abandon hope. Without hesitation they leaped out, falling (according to Béziers) twenty metres into deep, soft snow. The unweighted balloon promptly soared and disappeared, carrying with it their food and clothing, as well as the unfortunate pigeons. The aeronauts climbed down a precipitous mountain, and walked and stumbled for hours without finding any signs of civilization; least of all any clue, as to what part of the world they had landed in. Was there any terrain like this to the west of Paris? Where were they? In the Vosges mountains? The Black Forest? But what about the sea they had traversed? Exhaustion was setting in, and several times Rolier collapsed in the snow. Then, as night was falling and it seemed only a matter of time before Rolier succumbed to a lethal urge to sleep, they came across a ruined cabin, where they spent the night. The next day they resumed their march and eventually reached a poor hovel, tenanted but empty. They ate what they could find, and a few hours later two peasants clad in furs appeared, speaking a strange language. The French tried to explain their presence by drawing sketches of their balloon; but without success.

It was not until one of the peasants lit a fire with a box of matches marked ‘Christiania’ that Rolier and Béziers realized that they had landed in the centre of Norway! In fifteen hours they had travelled nearly nine hundred miles from Paris; it was a voyage worthy of the imagination of Jules Verne. The aeronauts were taken to Oslo (then called Christiania), fêted by blonde young women draped in

tricolores

and banqueted for several days like visiting gods, then returned home.

1

Astonishingly enough, both their balloon with its pigeons as well as the sacks of dispatches jettisoned into the sea eventually turned up, safe and sound. The latter were brought in by a fishing boat, and at once expedited to France by the French Consul. But they

were to reach Tours too late for Gambetta to do anything about co ordina ting with Trochu’s break-out.

Inside Paris, Trochu was just as much in the dark about Gambetta’s advance towards him—so essential to the success of the ‘Great Sortie’ on which the city’s defenders were staking their all—as Gambetta was about Trochu’s plans. In actual fact, after the recapture of Orléans, Aurelle seems to have been stricken with mental paralysis, or alarmed by his own success. For the best part of a fortnight he had sat still, vigorously disputing the next move with Freycinet. During this lost fortnight (a fatal one for France), when Aurelle had bogged down at Orléans and Ducrot was switching fronts in Paris, Prince Frederick-Charles was marching the Prussian Second Army rapidly westwards from Metz, whose surrender had released it. By the end of November it was firmly in position between Orléans and Paris, able to intervene in either direction.

The Great Sortie—Ducrot crosses the Marne

10. The Great Sortie

A

BOUT

the time that the Government was pinning its hopes on the break-out across the Marne, the voice of Victor Hugo was heard once more. This time he wrote, more soberly, in a new poem entitled

‘Paroles dans l’Épreuve’

;

Nous arrivons au bord du passage terrible;

Le précipice est là, sourd, obscur, morne, horrible;

L’épreuve à l’autre bord nous attend; nous allons,

Nous ne regardons pas derriére nos talons;

Pâles, nous atteignons l’escarpement sublime,

Et nous poussons du pied la planche dans l’abime

.

1