The Exploits of Moominpappa (Moominpappa's Memoirs) (3 page)

Read The Exploits of Moominpappa (Moominpappa's Memoirs) Online

Authors: Tove Jansson

me, boredom when you ought to enjoy yourself is the worst kind of boredom.

I went and called on the hedgehog.

'Well?' she said. 'Only don't say a word about Hemulens.'

'No, no,' I said. 'But won't you come and look at my house? We could sit there for a while and have a chat. I'll tell you all about my strange birth.'

'That would be fascinating,' said the hedgehog. 'I'm so sorry I haven't got the time. I'm making milk-bowls for all my daughters.'

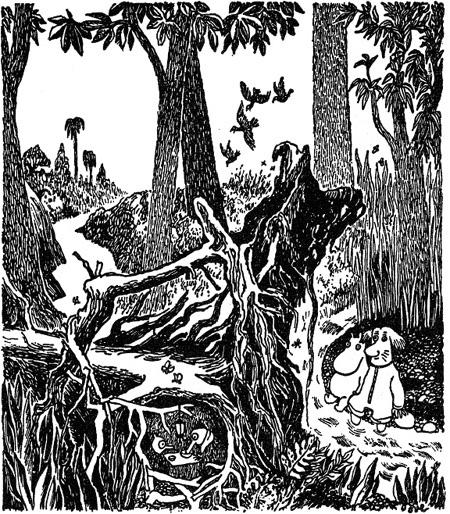

And that went for all the people in the wood. The birds, the worms, the tree-spirits, and the mousewives seemed to be in a great hurry about something or other. Nobody wanted to look at my house, or hear about my escape, or about the strange way I came into the world.

I went back to my green garden by the brook and sat down on the verandah. My verandah. My lonely fretwork verandah.

And suddenly - click - I had a new idea: to find out where the brook led.

I stepped into the cool water and began wading downstream. The brook ran as brooks do; with many freaks and

no hurry. Sometimes it rippled along, clear and shallow, over lots and lots of pebbles, and sometimes the water darkened and rose up to my snout. There were blue and red water-lilies floating everywhere in the stream. The sun was already setting and shone straight in my face. And after a while I began to feel almost happy again.

Then I heard a funny little whirring noise. Straight in front of me a splendid water-wheel was spinning. It was made of small sticks and stiff palm-leaves.

And somebody said: 'Please be careful.'

I looked up and saw a couple of hairy ears in the long grass by the brook.

'I'm just looking,' I said. 'Who are you?'

'Hodgkins,' said the owner of the ears. 'And you?'

'The Moomin,' I said. 'A lonely refugee born under rather special stars.'

'What stars?' asked Hodgkins, and his question made me very happy, because it was the first time anybody had asked me something I wanted to answer.

So I went to the shore and sat down at his side, and there I told him everything that had happened to me since the day I was found in the newspaper parcel. (Only I told him it had been a small basket of leaves.) And all the time the water-wheel was spinning in a little cloud of glittering waterdrops, and the sun reddened and sank, and my heart found new peace and happiness.

'Strange,' said Hodgkins when I had finished. 'Rather strange. That Hemulen. Bit of a cad, I think.'

'Quite,' I said.

'Not many worse, are there?' said Hodgkins.

'Certainly not,' I said.

Then we were silent for a while and looked at the sunset.

It was Hodgkins who showed me how to construct a water-wheel, an art that I have later taught my son. (Cut two forked branches and stick firmly in stream. Sandy bottom is best. Choose four stiff leaves, cross to form a star, pierce with stick. Strengthen construction with twigs. Carefully place stick on forks, and wheel will turn.)

In the evening twilight Hodgkins and I walked back to my house and I asked him in.

He said it was a good house. (Thereby he meant that it was a wonderful and fascinating house. Hodgkins never cared much for big words.) The night wind came and sang us a song.

I had now found my first friend, and so my life was truly begun.

CHAPTER 2

Introducing the Muddler and the foxter, and presenting a spirited account of the construction and matchless launching of the houseboat

.

W

HEN

I awoke the following morning Hodgkins was already casting a net in the brook.

'Hello,'

I

said. 'Any fish here?'

'Hardly,' said Hodgkins. 'Still, we might catch something else. Want to come and meet the Muddler?'

We locked the door and went.

The Muddler lived quite near. He was very small and muddly, Hodgkins told me, and he had made himself at home in an American coffee tin; the blue kind.

'Is he a relative of yours?' I asked.

'My nephew,' Hodgkins said. 'Adopted him. Father and mother disappeared in a spring-cleaning.'

'How terrible,' I said. 'Were they never found?'

'Never,' Hodgkins answered.

He took out his cedarwood whistle that had a pea inside, and whistled twice.

The Muddler came running at breakneck speed, trying to beat his tail and flap his ears and whisk his whiskers at the same time.

'Evening!' he cried. 'Why, that's grand! Whom are you bringing? Gee, what an honour! Excuse me please, things are a bit upside-down in my tin, but if you'd just...'

'Never mind,' Hodgkins said. 'We're just out for a walk. Want to come along?'

'Why, sure!' the Muddler cried. 'Just a minute, please, I'll have to bring a few things along...'

And he disappeared inside his tin where we heard him start a terrific rummaging. After a while he came out again carrying a wooden box under his arm, and so we all walked along together through the wood.

'Dear nephew,' Hodgkins suddenly said. 'Can you paint?'

'Can I paint!' exclaimed the Muddler. 'Sure, I've painted portraits of all my cousins! A separate portrait of each and every one! Excuse me, do you need some extra special, A-

I

de-luxe painting done?'

'You'll see. It's a secret so far,' Hodgkins answered.

At that the Muddler became so excited that he started jumping about on his toes, and the string around his box snapped, and out tumbled a heap of his personal belongings, such as wire springs, paper clips, ear-rings, tins, dried frogs, cheese-knives, trouser-buttons, and pipe-cleaners, among other things.

'Well, well,' said Hodgkins and helped him to collect it all again.

'I had a really dandy piece of string once, only I lost it somewhere! Excuse me!' the Muddler said.

Hodgkins produced a strong length of rope and tied it around the box, and so we walked on again.

Finally, he halted by a large fig thicket and said:

'Enter, please.'

We made our way through the green bushes, stopped, turned our heads upwards, and exclaimed respectfully: 'A ship!'

It looked large and deep and strong, and its blunt stem disappeared out of sight somewhere in the shadows of the thicket.

'My houseboat,' Hodgkins said.

'Your what?' I asked.

'Houseboat,' Hodgkins repeated. 'A house built aboard a boat Or a boat built beneath a house. You live aboard. Nice and practical.'

'And where's the house?' I asked.

Hodgkins let his paw describe a sweeping gesture, 'Your house by the brook,' he said.

'Hodgkins,' I replied, feeling a catch in my throat, 'when our mutual talents are joined there'll be no limit to their scope.'

By this time the Muddler had regained his breath and was able to shout: 'Gee, is it really true? Oh! May I paint that ship? Cross your heart?'

'Cross my heart, yes. Choose your own colour,' Hodgkins replied. 'But be careful about the water-line. And her name is

The Ocean Orchestra.

That's the title of my long-lost brother's book of poems. You'll have to paint the name marine blue.'

Glorious times! Immortal deeds! Triumphantly we marched back to my house and began moving it to the shipyard. 'Grab hold now,' said Hodgkins. 'Easy does it... Raise a bit more on that side! Now she moves...'

'Careful with the verandah, please!' I cried.

'Excuse me! The cellar got on my toes!' shouted the Muddler. And as he said it the house tipped up and a person came tumbling out of an upper window.

We looked at him.

'Hello!' I said threateningly.

'Hello yourself,' said the Joxter (for it was he).

'Why did you enter my house?' I continued.

The Joxter took his pipe from his mouth and explained genially: 'Because you had locked the door.'

'Sure, that's him all over!' cried the Muddler. 'He likes everything you mustn't do. He's always fighting policemen and laws and traffic signs.'

'And park keepers,' completed the Joxter, 'Has anybody had any breakfast yet?'

'No, quite the contrary,' said Hodgkins. 'Nephew! That pudding. Anything left?'

'Sure,' said the Muddler. 'Seen it yesterday.... Of course, my house is small and unworthy - but still - if I run along now and tidy it up a bit...'