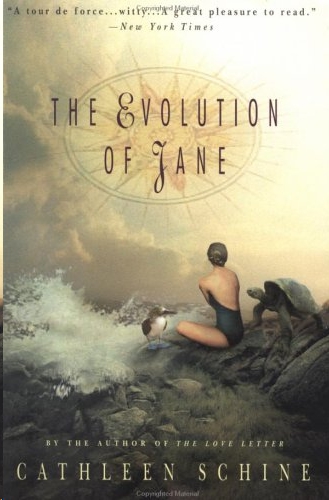

The Evolution of Jane

Read The Evolution of Jane Online

Authors: Cathleen Schine

Cathleen Schine

Table of Contents

Mariner Books

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

BOSTON NEW YORK

2011

First Mariner Books edition 2011

Copyright © 1998 by Cathleen Schine

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Schine, Cathleen.

The evolution of Jane / Cathleen Schine.—1st Mariner Books ed.

p. cm.

ISBN

978-0-547-52031-5

1. Americans—Galapagos Islands—Fiction. 2. Self-realization in women—Fiction.

3. Female friendship—Fiction. 4. Evolution—Fiction. 5. Galapagos Islands—

Fiction. 6. New England—Fiction. I. Title.

PS

3569.

C

497

E

9 2011 813'.54—dc22 2011005782

Book design by Melissa Lotfy

Printed in the United States of America

DOC

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSTo my brother, and friend, Ricky

Darwin ended

The Voyage of the Beagle

by noting that the traveler "will discover how many truly good-natured people there are, with whom he never before had, or ever again will have any further communication, who are yet ready to offer him the most disinterested assistance." To all those members of the American Littoral Society with whom I sailed on the

Galapagos Adventure,

I would like to say, Darwin was right, as always. Thank you for your help and your friendship. And for his generosity in sharing his pleasure in and understanding of the world, I would especially like to thank Mickey "Maxwell" Cohen, teacher, naturalist, guide, and, very simply, the world's best storyteller.

THE BARLOW FAMILY TREE

H

AVE YOU EVER LOST A FRIEND

? It is the saddest and most baffling experience. No one sympathizes, unless the friend died, which in my case she did not. I lost my best friend many years ago. She had been my best friend for almost a decade, for more than half of childhood, and then she evaporated, as though she had never really existed at all. Did anyone call me, try to console me, try to find a new friend for me? Yet when my husband left me after six months, I was bathed in sympathy and inappropriate blind dates. For that brief and absurd episode, I received the most tender consideration from all around me, most particularly from my family. Here is the story of my ex-husband: Michael and I were young and stupid; he, being young and stupid, left me for someone equally young and stupid; I, being stupid, cried for three months, and then, being young, woke up in the middle of the night, ate a bowl of cold leftover spaghetti, thought "This is pleasant," and cried no more.

But my mother had become convinced that I needed to "go abroad" in order to heal, and I did not disabuse her of this quaint notion. Although I was happier without Michael, I did feel regret at no longer being a wife, if only in an abstract sort of way. Going abroad had such a nice

amour-propre

-restoring ring to it.

"Off you go!" my mother used to say when she pushed me out the door to play, to stop me from moping around the house.

"Off you go!" she said after my divorce. "Off to the Galapagos!"

And so, like many wounded, world-weary souls before me, like Charles Darwin himself, I set sail for the Galapagos Islands. Is a visit to the Galapagos a very odd vacation? It seemed ideal to me the instant my mother suggested the trip. These islands were Darwin's territory, and my mother recalled my childhood infatuation with the bearded nineteenth-century naturalist. She remembered that I wanted to go to the Galapagos Islands when I was a little girl.

In my biography period, I read an illustrated account of the voyage of the H.M.S.

Beagle,

which marked the beginning of my fascination with Charles Darwin. What I remember most vividly from that book was, first, that Darwin was seasick for the entire five years of his voyage on the

Beagle,

and, second, that he had to be very tidy on shipboard. There were pictures of the cabinets used to store specimens, pictures of rows of little bottles and jars and wooden boxes, each labeled in an old-fashioned hand. Life on board ship seemed miniature, like a playhouse full of neatly organized treasures. I'm sure there were pictures in the book of other things as well—birds and volcanoes and ferns—but what I remember most were the boxes and drawers and their orderly tags.

I have had many heroes over the years. But Darwin was one of the earliest. And unlike some of those other early heroes—the Bionic Woman or Pinky Tuscadero, for example—Darwin has aged well. Perhaps because he was so imperfect, because he suffered, because he lived so many lives—a life of physical courage and adventure, a courageous and adventurous life of the mind, a quiet and settled family life. Perhaps because he was such a good gardener. I considered becoming a naturalist, like Darwin. The problem was that once outdoors, I became bored almost immediately. For a while, I persevered, usually by sitting inside thinking I should be a naturalist, sometimes by actually going outside and forcing myself to look at things.

During this time, like all my friends, I also read

The Diary of Anne Frank

and

The Story of My Life

by Helen Keller. But in addition to blindfolding myself and wandering around the living room to see what it was like to be blind the way we all did, and crouching in the attic with a bologna sandwich, hiding from Nazis, I used to look for fossils. I tired of being blind within a few minutes, and I tired of fossils almost as quickly, particularly because I never found any. I did, however, display and label a row of rocks from the driveway. I didn't know what they were and was too lazy to find out, so I just labeled them by color. But I still felt a proprietary bond with Darwin. Whenever I hear his name, to this day, I experience a sudden alertness, as if my own name has been spoken.

When Darwin was a young man, he collected beetles and loved to go shooting. He was supposed to be a doctor like his father, but at the first surgical demonstration in medical school, at the first sight of blood, he fainted. In his subsequent studies for the clergy, he spent most of his time carousing and turning over damp logs looking for insects. It was appealing to me to think that I was making the journey to Darwin's islands much as Darwin had—because the opportunity presented itself and life at home was too confusing. It's true that his parents did not send him to the Galapagos as mine did. In fact, his father was against the idea. But Darwin convinced his family. And so he sailed far, far away on a ninety-foot boat, just like me.

My mother gave me the restorative trip to the Galapagos as a twenty-fifth birthday present. This generous and

extravagant

gift was from both my parents, actually, but I knew it was my mother's idea. It had the scent of whim, and that's my mother's scent.

"You need to go far away," my mother said.

"Why not the Falkland Islands?" my father said. "That's even farther. And they have sheep."

"Jane is not interested in sheep, are you, Jane?"

"No, not really."

"You see? The Galapagos are perfect. There is not a single sheep."

My mother, a Spanish teacher, found out about this trip through a teachers' organization she belonged to. My father said perhaps she ought to send me to someplace normal, like Paris, for my birthday.

"No," I said. "The Galapagos will be far more consoling."

My father laughed. "I've always found you amusing, Jane," he said, "and so odd."

I hadn't thought much about Darwin or the Galapagos in years, but now, suddenly, as an adult, I wanted to go to those volcanic islands more than I ever had. I was no longer a wife. I had been stripped of my category. So where better to go than to the place where Darwin discovered so many new categories, the place where he discovered the very secret of categories? "I'm not a Coco Island finch anymore," said the little brown bird on the little brown island, "so what am I?" "You're a Darwin's finch," said Darwin. "And you, over there, you're a long-billed finch, and you're a vampire finch"—until all thirteen species of Galapagos finches were detected and named.

What exactly is a species? The definition of a species may seem a simple matter to you, but it puzzled and intrigued me whenever I thought about it, which I must admit was not that often until I prepared to visit Darwin's islands. But once you begin thinking about it, where do you end? I mean, what is it? How do you know? How do you decide? The idea that we all evolved from the same drop of ectoplasmic ooze I have always found to be perfectly reasonable. Nor is it biological diversity itself that alarms me. But look at one mockingbird and look at another. They appear similar, yet they are different species. Look at a Pekingese and a greyhound. They appear different, yet they are the same species.

In my defense, let me point out that the concept of species has changed drastically over the centuries. People have divided up flora and fauna into formal categories since Aristotle—but they keep changing the rules. These days, of course, there are recognized scientific criteria for determining an organism's species. But when I pored over my guidebook looking at pictures of birds and iguanas, I couldn't help wondering who decided what those scientific criteria were and, more important, how they decided. The Galapagos, the islands that had inspired Darwin to find the answers to all my questions, beckoned. I had seen those documentaries of courting blue-footed boobies and giant tortoises chewing cactus. The Galapagos were the frontier of species, and Darwin their pioneer. I was going where Darwin had gone, to see what Darwin had seen.

"You're searching for your roots," my father said, "on a dormant volcano?"

"They're not all dormant."

"Sturdy shoes!" my mother said. "And a hat!"

I had never gone anywhere with a group before, and I tried to tell myself that my Galapagos pilgrimage with the Natural History Now Society, arranged by my mother, would not be a week on a small boat with an assemblage of strangers, but an enriching apprenticeship. I knew there had to be a reasonable answer to the species question, and I guess I hoped that, traveling with a bunch of nature enthusiasts, I would find it.

The trip was in July, and I spent much of the month of June brooding on the nature of species and, in a less abstract but equally challenging vein, shopping. I had to find just the right backpack. I needed the best special quick-drying nylon shorts. There were microfiber shirts and bras and underpants to be acquired, pants that unzipped into shorts and padded moisture-wicking socks, snorkeling booties, gloves and a hood, a wet suit (long or short? how many milligrams thick?), snorkeling skin to wear beneath the wet suit, a Gore-Tex rain jacket, Tevas, summerweight hiking shoes, water bottles, hats, sunglasses, a strap to keep the sunglasses from falling overboard, and of course insect repellent, Dramamine, ginger pills, aloe lotion, and enormous bottles of mighty, waterproof sunscreen. The shopping was satisfying, even more satisfying than shopping normally is, for each purchase was so specialized, made for a reason. A teleological wardrobe. I sometimes think of shopping as a metaphor for life; that is, one tries so hard, picking and choosing, getting as much as one possibly can within one's budget, and then most of it goes in the closet, out of style or too tight in the waist. Then I remind myself that it's the shopping itself that really matters, not the purchases.