The Everything Theodore Roosevelt Book (47 page)

Read The Everything Theodore Roosevelt Book Online

Authors: Arthur G. Sharp

Tags: #History, #United States, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

Two of Nicholas’s children and their families split into two branches, one based at Oyster Bay, Long Island, the other at Hyde Park, New York. The Oyster Bay clan became Republicans; their cousins in Hyde Park gravitated toward the Democrat Party. Both factions grew prosperous and became serious about their duties and obligations to society. The die was cast for TR. He could not escape his fate as a “do-gooder.”

From almost the moment the first Roosevelts stepped off the boat in America, they became involved in business as merchants and planters and in politics. Some of them served in the military during the American Revolutionary War—”without distinction,” as TR noted. Others were members of the Continental Congress or other legislative bodies. TR was destined to continue the family’s activities in politics.

Passing on Family Values

Both of TR’s parents came from aristocratic families. His mother’s family was included on the list of wealthy, elite Georgia planters. They established a pattern for their children, which included formal and informal schooling and field training. Thee set the pattern for TR and his siblings.

TR downplayed the influence his mother played in his life. He said that she was a “sweet, gracious, beautiful Southern woman, a delightful companion and beloved by everybody.” She was a most devoted mother with a great sense of humor, he recalled, but for the most part it was his father from whom he learned the most in life.

One memory TR had about his mother’s sense of humor revolved around her Civil War Southern loyalty. She disciplined him one day, unjustly in his opinion. As retribution, he prayed loudly that night in her presence for the Union’s success in the war. She laughed and warned him not to do that again, lest she tell his father. He heeded her advice, and Thee did not learn about the incident.

TR overlooked the role she played in his life as he grew older, especially when he went to college. She did not want TR living on campus with the other students, which created some uncomfortable moments for him. Many of his classmates found it a bit odd that one of their peers was so pampered and antisocial.

There was a fine line between protection and overprotection in their view. His mother crossed that line. It was just one more obstacle that TR had to overcome in his struggle to become independent and accepted. That helps explain why he gave more credit to his father than his mother for molding him into a productive member of society who could stand on his own two feet.

Like Father, Like Son

TR always recalled fondly the lessons he inculcated from his father. Thee taught him and his siblings about their duties to society. His father was religious, brave, gentle, tender, unselfish, and, most of all, loving. He instilled those same virtues in his children.

And Thee made it clear there were certain things he would not tolerate in them. Selfishness, cruelty, idleness, cowardice, and lack of truthfulness topped the list. Thee relied on discipline and love to drive those virtues and vices into his children’s minds.

Above all, Thee made his children feel protected. TR always felt safe with Thee, but he knew that the protection only went so far. Thee expected the children to fight their own battles when necessary. He knew he would not be around forever to help them. Self-dependence was one of the biggest gifts he gave his children. It was one that TR learned well.

Thee was not averse to giving his children little gifts every now and then. That practice reinforced the notion of giving, even if the little things he gave had no extrinsic value but served merely as reminders of a father’s love for his children. TR passed the same types of gifts to his children later on.

TR invented his own reward system with his children. He remembered one in particular. Whichever child brought him his bootjack, a small tool that helped people pull their boots off, after he returned from a horse ride got to walk around the room in TR’s boots. That was a significant reward; it took someone special to fill his shoes.

In addition to passing down his own values to his children, Thee applied them outside the home. He worked hard at his business during the day and redirected his industriousness to social reform and charity works at night and on the weekends. He did not just give money to people or underwrite buildings. He visited the poor and downtrodden and took the children with him.

TR Tags Along

When Thee visited the hospitals, homes for orphans, the YMCA, and other places in which he had an interest, the kids went along. Often, when he taught a Bible class at Madison Square Presbyterian Church, as he did many Sunday nights, TR was there. Later, when TR was at Harvard, he taught Sunday school classes.

TR emulated his father in many ways later in life. He may have done so in word only during his formative years by paying lip service to fighting graft and corruption and protecting the weaker elements of society. Later, he became more serious about helping those who needed help.

The ideas he formed about seeking social justice came largely from his father. He simply carried them out on a much larger stage when the opportunity arose.

Nathan Miller described TR’s father in his book,

Theodore Roosevelt, A Life

, as “either founder or early supporter of almost every humanitarian endeavor in [New York] city.” He added, “In extending a hand to those less fortunate than himself, he acted from a disciplined sense of obligation as a Christian and a gentleman. Good fortune, he believed, must be balanced with productive work and service.”

Carrying the Torch

TR’s letters to his children are filled with pieces of advice regarding success, how to achieve it, and what he expected of them. He was accomplishing two purposes through the letters: expanding on the advice handed down to him and integrating it with his own experiences.

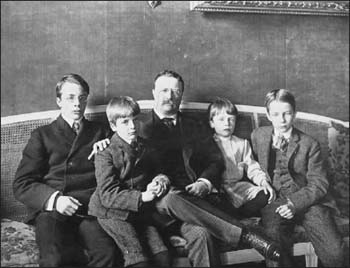

President Theodore Roosevelt with his boys, 1904

In one letter to Theodore Jr., TR sums up his attitude about life in general and what he hoped his children would do: “I always believe in going hard at everything, whether it is Latin or mathematics, boxing or football, but at the same time I want to keep the sense of proportion. It is never worthwhile to absolutely exhaust one’s self or to take big chances unless for an adequate object.”

There was a lot of TR and his father in those letters. He discussed every conceivable subject in them, but the underlying theme in almost every one was to “do your best” and “you and the world will be better for it.”

He mentioned Edith often, but as a sort of postscript. “Mother has gone off for nine days …” “Mother and I have just come home from a lovely trip to Pine Knot …” “Mother was away [so] I made a point of seeing the children each evening for three-quarters of an hour or so …” It was a throwback to his own upbringing: “Mother” was in the background, while “Father” dispensed the advice to the children.

But, that was TR: always in charge—except when Edith took a page out of his book and made decisions such as buying Pine Knot, introducing innovations in the White House, and deciding when he needed a vacation.

TR may have been deluding himself at times about who was in charge. In an April 30, 1906, letter to Kermit, he wrote: “On Saturday afternoon Mother and I started off … Mother having made up her mind I needed thirty-six hours’ rest, and we had a delightful time together, and she was just as cunning as she could be.” Edith suggested; TR obeyed.

Regardless of whom he was writing to, and what the subject was, one thing shone through: TR was a proud father overseeing a mostly happy family.

TR, Edith, and Family Life

His children were the focal point of TR’s life. Whether they were at Oyster Bay or in the White House, he made time for them. When he was away, he missed Edith and the children.

Fortunately for TR, he served as president at a time when the position did not require extensive travel, especially outside the country. So he could do a lot of his work at Oyster Bay or in Washington, D.C., and live and play with Edith and the children when they were growing up. Much of that “work” involved corresponding with his family.

A May 10, 1903, letter TR wrote from California to Quentin demonstrated how homesick he could get when he was traveling: “I am very homesick for mother and for you children; Whenever I see a little boy being brought up by his father or mother to look at the procession as we pass by, I think of you and Archie and feel very homesick.” Homesickness and “presidenting” went hand in hand.