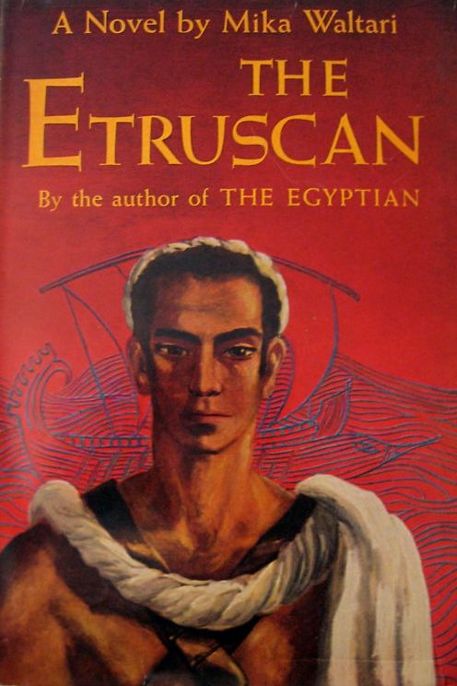

The Etruscan

The Etruscan

by Mika Waltari

Translated by Lily Leino

© 1956 by G. P. Putnam’s Sons

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission. Published on the same day in the Dominion of Canada by Thomas Alien, Ltd., Toronto.

Library of Congress Catalog

Card Number: 56.13140

Table of Contents

Delphi 5

Dionysius of Phocaea 71

Himera 154

The Goddess of Eryx 265

Voyage to Eryx 428

Dorieus 527

The Siccani 643

The Omens 801

The Lucumo 991

Delphi

1.

I, Lars Turms the immortal, awakened to spring and saw that the land had once again burst into bloom.

I looked around my beautiful dwelling, saw the gold and silver, the bronze statues, the red-figured vases and the painted walls. Yet I felt no pride, for how can one who is immortal truly possess anything?

Prom among the myriad precious objects I took up a cheap clay vessel and for the first time in many years poured its contents into my palm and counted them. They were the stones of my life.

Then I returned the vessel with its pebbles to the feet of the goddess and struck a bronze gong. Servants entered silently, painted my face, hands and arms sacred red and clothed me in the sacred robe.

Because I did what I did for my own sake and not for my city or my people, I did not let myself be borne on the ceremonial litter but walked on my own feet through the city. When people saw my painted face and hands they stepped aside, children paused in their games, and a girl by the gate ceased playing her pipes.

I stepped out of the gate and descended into the valley along the same path that I once had followed. The sky was a radiant blue, birdsong echoed in my ears and the doves of the goddess cooed. The people toiling in the fields paused respectfully at sight of me, then turned their backs once more and continued their work.

I did not choose the easy road to the holy mountain, that which was used by the stonecutters, but the sacred stairs flanked by painted wooden pillars. They were steep stairs and I ascended them backward, looking down on my city the while, but although I stumbled many times, I did not fall. Even my attendants, who would have steadied me, were afraid, for never before had anyone ascended the holy mountain in such a manner.

When I reached the sacred path the sun was at its zenith. Silently I passed the entrances to the tombs with their stone mounds, and passed also my father’s tomb before I reached the summit.

Before me in every direction stretched my vast land with its fertile valleys and wooded hills. To the north gleamed the dark blue waters of my lake, from the west rose the tranquil cone that was the goddess’ mountain, and opposite it the eternal dwellings of the deceased. All this had I found, all this had I known.

I looked about for an omen and saw on the ground the newly fallen feather of a dove. I picked it up, and as I did so saw beside it a small reddish pebble. This too I took into my hand. It was the last stone.

Then I stamped the ground lightly with my foot. “This is the place for my tomb,” I said. “Hew it from the mountain and ornament it as befits my state.”

My bedazzled eyes saw shapeless beings of light streaking through the skies as I had seen them only on rare occasions in the past. I raised my arms before me, palms down, and a moment later that indescribable sound which a man hears but once in his lifetime echoed through the cloudless sky. It was as the voice of a thousand trumpets, quivering through land and air, paralyzing the limbs but swelling the heart.

My attendants sank to the ground and covered their faces, but I touched my forehead, extended my other hand into space, and greeted the gods.

“Farewell, my era. The century of the gods has ended and another has begun, new in deeds, new in customs, new in thoughts.”

To my attendants I said, “Arise and rejoice that you have been privileged to hear the divine sound of the changing era. It means that all who last heard it are dead and none among the living will hear it again. Only the yet unborn will have that privilege.”

They still shook, as did I, with the trembling that comes to a person only once. Clutching the last stone of my life, I again stamped on the site of my tomb. As I did so a violent gust of wind swept over me, and I doubted no longer but knew that some day I would return. Some day I would rise from the tomb new of limb, to hear the roar of the wind under a cloudless sky, to smell the resinous fragrance of the pines in my nostrils and see the blue mound of the goddess’s mountain before my eyes. If I remembered to do so, I would choose from among the treasures in my tomb only the humblest clay vessel, pour the pebbles into my palm, hold them one by one, and relive my past life.

Slowly I returned to my city and dwelling along the path over which I had come. The pebble I dropped into the black clay vessel before the goddess, then covered my face with my hands and wept. I, Turms the immortal, shed the final tears of my mortal being and yearned for the life that I had lived.

It was the night of the full moon and the beginning of the spring festival. But when my attendants sought to wash the sacred color from my face and hands, to anoint me and to place a wreath of flowers around my neck, I sent them away.

“Take of my flour and bake the cakes of the gods,” I said. “Choose sacrificial animals from my herd and also give gifts to the poor. Dance the sacrificial dances and play the games of the gods according to custom. But I myself shall retire to solitude.” Nevertheless, I asked both augurs, both interpreters of lightning and both sacrificial priests to make certain that all was done as custom decreed.

I myself burned incense in my room until the air was heavy with the smoke of the gods. Then I stretched out on the triple mattress of my couch, crossed my arms tightly across my chest, and let the moon shine on my face. I sank into a sleep which was not sleep until my limbs became immobile. Then it was that the goddess’s black dog came into my dream, but no longer barking and wild-eyed as before. It came gently, leaped into my lap, and licked my face. In my dream I spoke to it

“I will not have you in your underworld guise, goddess. You have given me unwanted wealth and power that I have not craved. There are no earthly riches with which you could tempt me to content myself

with you.”

Her black dog vanished from my lap and the feeling of oppression passed. Then the arms of my lunar body, transparent in the moonlight, reached upward. Again I rejected the goddess. “Not even in my heavenly shape will I worship you,” I said.

My lunar body ceased to delude me. Instead, my guardian spirit, a winged being fairer than the fairest human, took shape before my eyes. She was more alive than any mortal as she approached and seated herself on the edge of my couch with a smile.

“Touch me with your hand,” I implored, “that I may know you at last. I am tired of lusting for all that is earthly and desire only you.”

“Not yet,” she replied. “But some day you will know me. Whomever you have loved on earth you have loved only me in her. We two, you and I, are inseparable but always apart until that moment when I can take you in my arms and bear you away on my powerful wings.”

“It is not your wings that I long for but you yourself,” I said. “I want to hold you in my arms. If not in this life, then in some future life I shall compel you to assume a human shape so that I may discover you with human eyes. Only for that reason do I want to return.”

Her slender fingers caressed my throat. “What a dreadful liar you are, Turms,” she murmured.

I gazed on her flawless beauty, human yet flamelike. “Tell me your name that I may know you,” I pleaded.

“And how domineering you are,” she smiled. “Even if you knew it you could not rule me. But do not fear. When I finally take you in my arms I shall whisper my name in your ear, although you probably will have forgotten it when you awaken to the thunder of immortality.” “I don’t want to forget it,” I protested. “You have done so in the past,” she declared.

No longer able to resist, I extended my arms to embrace her. They closed over nothing, although I still saw her alive before me. Gradually the objects in the room became visible through her being. I sprang up with a start, my fingers clutching at moonbeams. Disconsolately I paced the room, touching the various objects, but my arms lacked strength to lift even the smallest. Again a feeling of oppression came over me and I struck the gong with my fist to summon a human companion. But no sound emanated from it.

When I awakened I was lying on the couch with my arms crossed tightly over my chest. Finding that I could move my limbs, I sat on the edge of the couch and hid my face in my hands.

Through the incense and the terrifying moonlight I tasted the metallic flavor of immortality and smelled its icy scent. Its cold flame nickered before my eyes, its thunder roared in my ears.

I rose defiantly, flung wide my arms and shouted, “I do not fear you, Chimera. I still live the life of a human. Not an immortal but a human among my own kind.”

But I could not forget. I spoke again to her who ever hovered around me invisibly, protecting me with her wings.

“I confess that all I have done of my own selfish will has been wrong and harmful to myself as well as to others. Only in following your guidance, unknowingly and as one who walks in his sleep, have I unerringly done the right thing. But I must still learn for myself what I am and why I am thus.”

Having clarified that, I taunted her. “It is true that you have done your utmost to make me believe, but I do not. So much a human am I still, I will believe only when I awaken in some other life to the roar of the storm and remember and know myself. When that happens I shall be your equal. Then we can better dictate our terms to each other.”

I took the clay vessel from the feet of the goddess, took one pebble after another in my palm and remembered. And having remembered, I wrote down everything to the best of my ability.

The majority of men never stoop to pluck a pebble from the ground and save it as a symbol of the end of one era and the beginning of another. Thus it is forgivable if relatives place in the vessel a heap of pebbles equaling in number the years and months of the deceased. In that case the pebbles reveal his age but nothing else. He has lived the ordinary life of a human and been content.

Nations also have their eras, known as the centuries of the gods. Thus we immortals know that the twelve Etruscan peoples and cities have been allotted ten cycles in which to live and die. We refer to them as lasting one thousand years because it is easy to say, but the length of a cycle may not necessarily be even one hundred years. It may be more or even less. We know only its beginning and its end from the unmistakable sign we receive.

A man seeks the certainty that cannot be had. Thus the soothsayers compare the liver of a sacrificed animal with a clay model which is divided into compartments, each bearing the name of a particular deity. Divine knowledge is lacking, therefore they are fallible.

Similarly, there are priests who have learned many rules of divining from the flight of birds. But when they are confronted by a sign with which they are not familiar they become confused and make their predictions blindly. I will not even mention the interpreters of lightning who ascend the holy mountains before a storm and confidently interpret the thunderbolts according to color and position in the vault of heaven, which they have quartered and orientated and divided into sixteen celestial regions.

But I shall say no more, for thus it must ever be. Everything grows rigid, everything ossifies, everything ages. Nothing is sadder than obsolescent and withering knowledge, fallible human knowledge instead of divine perception. A man can learn much, but learning is not knowledge. The only fountainheads of true knowledge are inward certainty and divine perception.

There are divine objects of such potency that the sick are healed by touching them. There are objects which protect their bearers and others which harm. There are sacred places which are recognized as sacred although no altar or votive stone marks their site. There are also seers who are able to view the past by holding an object. But no matter how convincingly they speak to earn their porridge and oil, it is impossible to know how much of what they say is true, how much merely dream or fabrication. Not even they themselves know. To that I can testify, for I myself have the same gift.