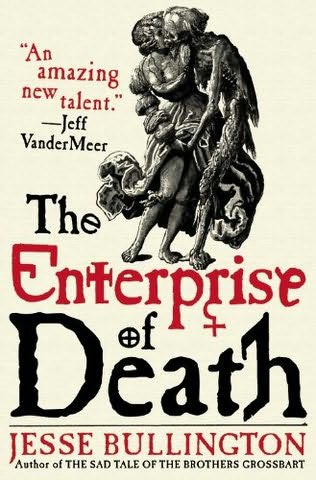

The Enterprise of Death

Read The Enterprise of Death Online

Authors: Jesse Bullington

“Darkly funny, profane, erudite, bawdy and wickedly original … an amazing new talent.”

Jeff Vandermeer

“An engrossing read.”

Interzone

“A novel of great humour, deep theology and gratuitous murder and quite unlike anything I’ve ever read before. I absolutely loved it … one of the books of the year for sure!”

“The wicked sense of amorality and humour will appeal to many who like their humour dark. Like its amazing cover, it is a satisfyingly clever, well-plotted book that never takes itself too seriously.”

“This is one of the best I’ve read … utterly absorbing and as fine a tale as you’ll read this year.”

Sci-Fi London

“Bullington paints a world appropriately dark and sinister with a confidence that makes you wonder whether he knew someone who lived there.”

“Dark, brooding, atmospheric and compelling.”

Booksmonthly.co.uk

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 978-0-748-11880-9

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2011 by Jesse Bullington

Extract from

The Sad Tale of the Brothers Grossbart

by Jesse Bullington

Copyright © 2009 by Jesse Bullington

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

For

All Those Who Go Before Us

Prologue: The Worst Beginning Imaginable

II: The Coming of His Acolytes

IV: The Three Apprentices of the Necromancer

IX: Medicines Bitter as Wormwood

XII: Something Sweeter Than Unspoiled Wine

XIV: The Long Walk to Golgatha

XVIII: A Discharge, with Some Weeping

XXIV: The Whores, the Boors, and the Moor

XXVI: Necromancers and Other Scavengers

XXVII: The High Cost of Living

XXIX: A Fast Night in the Black Forest

XXXI: A Slow Night in the Black Forest

XXXII: The Convergence of Trails

XXXIII: Bastards of the Schwarzwald

XXXV: A Tale for a Colder Night

The Sad Tale of the Brothers Grossbart

The Worst Beginning Imaginable

Pity Boabdil. King of Granada, last Moor lord of the Iberian Peninsula, reduced to a suppliant outside his own city by a Spaniard sovereign, an exile from a home hard won. The truce signed by kings and Pope, all that remained was for Boabdil to bow before his victorious adversary and kiss the man’s ring. The victor was supposed to refuse the offer, thus preserving some shred of Boabdil’s already tattered honor, but this stipulation must have slipped the Christian’s mind as he extended his pudgy fingers to the Moor. There was nothing for it. King Ferdinand’s seal tasted salty as the strait Boabdil would soon cross, and the man’s onion-pale queen leered at the Moor as he rose.

That dreadful Genoan sailor who hung around Isabella like a fly around a chamber pot stood a short distance off, and when they made eye contact Boabdil supposed the weather-beaten bastard was imagining his head on a pike. At the signing King Ferdinand had mentioned something about the explorer sailing for India the wrong way round and Boabdil had paid it no real mind until now, with the scheming seaman appraising the former ruler of Granada’s venerable pate. Boabdil hoped he drowned.

The handover continued, a grand display of pageantry and pomp, with the humbled Boabdil bowing in all the proper places as the procession carrying aloft a weighty silver cross all but stuck

out their tongues at the defeated Moors leaving the city. Of course the treaty had many articles detailing how the Moors who chose to stay in Granada or thereabouts would retain all their rights and be under no pressure to convert and be protected as they had before, and of course each and every article would be cast down and shattered before Boabdil’s mustaches gained even a few ashen strands. The Christians had given him a token patch of broken Spanish earth upon which to reestablish his noble person, but Boabdil held no illusions, and so south they departed to sail to a continent Boabdil had never known.

When they came to a prominence upon the road where Boabdil could view the Alhambra of Granada one final time, history recalls the heavy sigh that escaped his lips, a sigh as weighty as if the whole country issued it. Indeed it might have—with the passing of Boabdil the tolerance and culture that the Moors had slowly cultivated over hundreds of years of conquest was likewise expelled, and within Boabdil’s lifetime the Jews and Moors who lived at peace with the Spanish Christians would be banished, murdered, or forcibly converted, the lanterns of illumination that mutual respect fosters traded for brands used to burn Qur’an and witch alike. Small wonder Boabdil might sigh, and smaller wonder still that this most famous of sighs was actually a ragged, choking sob.

“Must you cry like a woman over that what you could not hold as a man?” his mother asked him, which, predictably, only made him weep the harder. She could be unfair, could Boabdil’s mother.

Boabdil did not simply cry for his lost kingdom, he cried for his lost daughter. The son the Spaniards had kept ransom during the siege of Granada had been returned, but in his place Ferdinand, ever the son of a bitch, had claimed Boabdil’s daughter Aixa, and there was not a single thing the broken old ruler could do about it. A king should love his sons most, of course, but

Boabdil was no longer king and so allowed his sorrow to run down his face in snotty dribbles.

The viscous, golden grief dangling from Boabdil’s nose and lips as his belly shook with emotion made him look for all the world like a walrus chased off a honeycomb by a greedier bear, for Ferdinand’s piggy little eyes and boxy jaw lent him something of an ursine face. None present had ever seen a walrus, however, and the only man who had encountered a bear was Boabdil’s second cousin, who had been severely mauled by the beast on a hunting expedition. The poor fellow had to be carried around in a lidded basket to keep those weak of stomach from fainting at the sight of the gnawed-up stumps where his legs used to be and the terrible scars crisscrossing his face. The result was that no one commented on the walrus-and-bear imagery, and Boabdil’s second cousin spent the rest of his life haunted by nightmares of the furry monster that had put him in his box. Pity Boabdil’s second cousin.

Ferdinand, king of This, That, the Other, and now Granada, was very fond of sexual relations so long as they were not with his wife. It was Isabella’s eyes, eyes so widely spaced she looked more sardine than woman, and seafood gave him gout. That the portly Boabdil had sired such a gorgeous girl as Aixa pleased Ferdinand greatly, and almost quicker than he felt the pinch in his hose the lecherous ruler had her baptized, renamed after his wife—a coup to Ferdinand, but a choice that unsettled everyone else he told about it—and established as a mistress. Behaving in a beastly fashion to Moors was something of a hobby for Ferdinand, and so as Boabdil kissed his ring that fateful January day in 1492 the conquering king murmured in his fallen adversary’s ear that were Boabdil to send him a beauty who outshone Aixa then the Moor should have his daughter back, thereby ensuring Boabdil knew just what carnal fate awaited his beloved child.

The time for pitying poor Boabdil has now passed. Upon

emigrating to North Africa and settling in Fez, the still obscenely wealthy Moor did little but acquire pretty young girls in hopes of offering one to his old enemy. He thought his daughter peerless in beauty, however, and as the years passed and —whether or not he would admit it even to himself—his memory faded, he remembered his daughter as being yet prettier and prettier still, until a manifest goddess would have been hard-pressed to get an approving nod from the gloomy old walrus, and so none of the bought women ever made it further than his personal harem.