The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars (68 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Online

Authors: Jeremy Simmonds

At the start of 1980, the group toured Europe. Ian Curtis, unbeknown to his wife, was continuing a fractured affair with Annik Honoré, a Belgian Embassy journalist and fan of his band whom he’d met late the previous year. Despite the emotional problems this was causing him, Curtis chose to take Honoré to the Continent with the band. On his return – consumed by guilt and self-doubt –Joy Division’s frontman attempted suicide, collapsing after downing a bottle of duty-free Pernod and slashing pages from a Bible as well as his own wrists. (Or so he was to tell his bandmates: that he had actually cut only his torso was less self-destructive, if no less dramatic.) But Curtis’s situation was having a detrimental effect on his physical health as well as psychologically. The traumas of this period in his life were documented in Joy Division’s second album – their last work. If

Unknown Pleasures

was a compelling debut, follow-up

Closer

(1980) seemed sculpted in ice, and was probably the group’s finest hour. With Deborah Curtis now aware of her husband’s infidelity, the album was recorded when their marriage was at its most vulnerable. Honoré, who had attended the London sessions, recognized the guilt and despair in tracks like ‘Isolation’, ‘Twenty-Four Hours’ and ‘Decades’ once Ian had told her they had to break up. Following a frenetic series of concerts that played havoc with his physical routine and destabilized his condition, Curtis suffered a severe grand mal attack during a London gig, which saw him crash into the drum kit. His jilted lover waited backstage, wanting little to do with a situation she clearly found embarrassing. On returning home to Macclesfield, the depressed singer attempted suicide once more, consuming a lethal dose of his medication, phenobarbitone. This time Curtis was hospitalized and had left a note – there was now much more cause for concern, despite his protestations to his colleagues that he was ‘just fucking around’. In late April, recording the single ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ and its accompanying video took his mind off matters. But only temporarily.

Just over a month later, divorce from Deborah imminent, Ian Curtis cancelled an (unlikely) afternoon’s water-skiing with Bernard Sumner on the eve of Joy Division’s first tour of the US. He chose instead to spend the evening alone in his house drinking coffee and whisky as he played Iggy Pop’s

The Idiot

and watched Werner Herzog’s

Stros%ek

– an art-house film about a man who kills himself rather than choose between two lovers. In the early hours of 18 May, the confusion and hopelessness of his situation now too much to bear, Curtis scrawled a lengthy note to his estranged wife and hanged himself from a clothes rack in their kitchen. It was Deborah who found his body, returning from her parents’ home the following midday, by which time any attempts to revive the singer were futile. Those around him were devastated by news they’d feared (suicide is, after all, five times more prevalent among epileptics than those in normal health). Deborah, however, was the hardest hit by Curtis’s suicide: ‘I felt angry with him because he’d had the last word. But how can you be angry with someone who’s dead?’ Honoré – whose affair with the singer had been briefly resurrected – reportedly sat in his temporary room at Anthony Wilson’s home continually playing

Closer.

The album achieved UK Top Ten status on the back of the tragedy, while ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ has, of course, become a classic: a Top Twenty hit on three occasions, it was shortlisted for a Brit Award in 2005 – though was somehow pipped by Robbie Williams’s ‘Angels’.

The aftermath of Ian Curtis’s death was almost as hard for the band as it was for his family, though the remaining members all knew early on that they

would

strive to continue. They adhered to an earlier band decision that a new name would be sought: the choice of ‘New Order’ was as unanimous as it was predictable. Dragging themselves away from their past, they went on to exactly the kind of international acclaim that Curtis had so desired. However, with this commercial acceptance for New Order’s music came belated worldwide recognition for the brief, extraordinary work of Ian Curtis and Joy Division. The final weeks of Curtis’s life were documented in the 2002 movie

24-Hour Party People,

while in 2007, the biopic

Control

– based on Deborah Curtis’s memoirs – was released in Europe.

JUNE

Sunday 1

Charles Miller

(Olathe, Kansas, 2 June 1939)

War

Saxophonist/singer Charles Miller was a founding member of timeless funk/rock exponents The Creators - later Nightshift, then War. The band were initially signed to back former US football star turned soul hopeful Deacon Jones but found a higher profile as back-up band to ex-Animals lead Eric Burdon. Overcoming the 1969 death of bassist and prime mover Peter Rosen before an album was even cut, the group managed a steady stream of hits throughout the seventies including ‘Me and Baby Brother’ (1973), ‘Why Can’t We Be Friends?’ (1975) and the excellent, much-borrowed ‘Low Rider’ (1976) before the rise of disco began to curtail their appeal.

Miller was shot dead, accidentally caught up in a Los Angeles street robbery that went tragically awry. The exact date of the incident remains unconfirmed, though had it been 1 June he would have been a day short of his forty-first birthday. War continued as a touring unit thoughout the decade.

See also

Papa Dee Allen ( August 1988)

August 1988)

JULY

Monday 14

Malcolm Owen

(London, 1955)

The Ruts

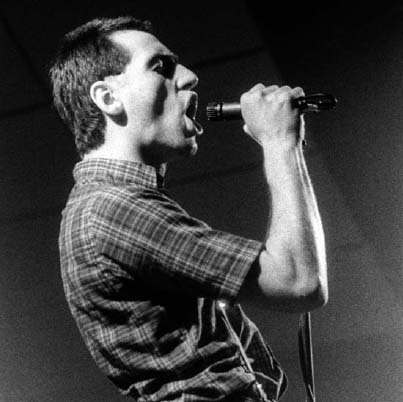

Frontrunners of the second wave of UK punk rock, The Ruts allied the powerful call-to-arms stance of The Clash with dynamic three-chord guitar thrash. The results – particularly the brilliant debut ‘In a Rut’ (1978) and Top Ten ‘Babylon’s Burning’ (1979) – saw to it that the London band had really arrived by 1980. Also, like Strummer and co, The Ruts were ready to work with black artists (issuing a single via the label of UK reggae act Misty in Roots) and to adopt disparate musical styles. Indeed, so eclectic was The Ruts’ following that their gigs probably heralded the first ever sighting of pogoing Pakistani fans – something that did not always sit well with a less welcome right-wing faction in their audience.

Singer Malcolm Owen had issues of his own, however – not least the breakup of his marriage and his subsequent return to the heroin habit he had acquired before forming the band. His death from an overdose abruptly ended a band with a great deal of potential – attempts to keep The Ruts alive proved futile.

See also

Paul Fox ( October 2007)

October 2007)

Malcolm Owen: In a rut and couldn’t get out of it

Monday 21

Keith Godchaux

(San Francisco, California, 9 July 1948)

The Grateful Dead

(Ghost)

(Dave Mason)

By the time 25-year-old keyboardist Keith Godchaux joined them full-time from Dave Mason’s band, in 1972, Jerry Garcia’s Grateful Dead were already legendary, true hippy survivors of the Haight-Ashbury scene – and fast becoming the biggest touring band in the USA. The departure of keyboard-player Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan had left a large hole and necessitated a change. Godchaux, while a more technically able musician, was not of the same calibre as the founder member in terms of presence or showmanship. This fact became something of an albatross to Godchaux – particularly after the popular McKernan’s tragic death a year later ( March 1973).

March 1973).

The new man made himself even less popular by installing his wife, Donna, as a back-up soprano vocalist: her inconsistent performances often alienated the hardcore fanbase. As a result, the couple’s 1975 solo album took a critical and commercial panning. It was an uphill struggle that Godchaux couldn’t win: after six years with The Dead, he and his wife were asked to leave in 1979.