The Emperor of Lies (22 page)

Of the six hospitals in the ghetto, Hospital No. 1 in Łagniewnicka Street was the largest. Its ground plan was square, with two wings extending from the main building round an open courtyard. So the building could be approached from a number of different directions.

In a desperate attempt to make contact with her father, Vĕra went in the back way, through dense shrubbery between some huts and a shed, to the separate entrance for the maternity wing. Many of the vehicles were already in place, parked there with their trailers. SS soldiers in field-grey uniforms with leather belts and tall, shiny boots were idling away their time round the drivers’ cabs or on the backs of the lorries. The soldiers’ passivity was deceptive, however. She got almost as far as the loading bay at the back entrance to the hospital when a shrill whistle cut through the air. When she looked up, she saw a man in uniform appear at a wide-open window on the second floor. Then a naked baby was pushed out, and fell headlong, straight down onto the back of the waiting lorry.

One of the soldiers on the lorry – a young man with bright blond hair and a uniform that looked several sizes too big for him – stood up and waved his rifle to his colleague on the second floor. The sleeves of his jacket were so long that he had to turn them up before he could attach his bayonet. Then he stood there, legs planted wide apart, while more squealing infant bodies came raining down from the window. Whenever he skewered one of the babies on his bayonet, he lifted it high above the end of his rifle, the blood running down his rolled-up sleeves.

Somewhere in the building above, people must have noticed what was happening, for other windows opened, and from inside came the sound of screaming in Yiddish and Polish:

Murderers, murderers . . . !

Vĕra didn’t know what to do. As if spurred on by the commotion, even more German soldiers appeared on the second floor. They were all cradling infants at their uniformed chests.

Then Vĕra started screaming herself.

The face of the laughing soldier on the back of the lorry changed to an ‘O’ of astonishment. In an instant, he had torn the bloody bundle from the tip of his bayonet and turned the sights of his rifle on her.

The sudden volley of rifle fire sent leaves and chips of wood flying from the roof of the hut, just above her head. She ducked and ran, and out of the bushes around her other running figures also appeared. Some in hospital gowns, others almost completely naked, mostly women and elderly men. Her sudden scream, and the shots that followed it, had driven them out of their temporary hiding places and now they were all running – frightened out of their senses, lifting their feet in high, stalking steps – as the salvoes of rifle fire carried on whipping up gravel and grass from the dust in front of the figures that had not yet fallen.

*

At the midday break, she stood in the queue for the soup kitchen in Jakuba Street with her tin mug, the heat of the sun burning and stinging her unprotected head as if there were a huge, open wound under the skin.

Almost everybody in the soup queue had family members in the various ghetto hospitals, and they almost all had similar stories to tell: of children thrown from maternity wards straight down into the waiting lorries; of infirm old people who had come tottering out of their wards to be run through by bayonets or shot dead. Only a few of those returning from the hospitals had managed to bring their relatives home with them.

It was rumoured that the Chairman, after protracted negotiations, had persuaded the authorities to exempt some particularly high-ranking individuals among the sick, but only on condition that others would be deported in their stead. A new Resettlement Commission had been set up to go through the patient registers to identify former in-patients who had been discharged, or people who had previously applied for places but been turned down for lack of the right contacts; anything or anyone would do: as long as they could take the places of the

few irreplaceable

individuals that those in charge said they could not do without.

It’s a disgrace, an utter disgrace . . . !

Mr Moszkowski could be heard muttering as he walked in the clouds of fluff among the looms. It was as though someone kept poking him in the side with a big stick. As soon as he sat down, he was up on his feet again.

In the evening, news came through that the Chairman’s father-in-law and various relatives and close friends of Jakubowicz and police commissioner Rozenblat had been ‘bought out’ by

substitutes

stepping into their places. The only person the Chairman had not managed to bring down from the trailers was his brother-in-law, young Benjamin Wajnberger, for the simple reason that nobody seemed to know what had become of him. There was no sign of him at the hospital; nor had he been seen in any of the temporary assembly camps. Had he tried to escape and fallen foul of some German patrol? Regina Rumkowska was broken-hearted, and said she feared the worst.

The very first evening, the Schulz family received a visit from a certain Mr Tausendgeld. He was the one charged with arranging to get them out.

Much later, when the story came out of his violent death at the hands of the German torturers, Vĕra tried to remember his face. But the image of Mr Tausendgeld remained as indistinct as it had been then, as he sat with them in the kitchen alcove next to Maman’s little room. She remembered a face covered in lumps and bumps, and in it a mouth with small, sharp, pointed teeth that he bared every time he smiled. With his long, slim, strangely stalk-like hands, he spread what looked like long lists of names on the table and made a show of marking off names as he talked.

From inside her chamber, Maman called out to Vĕra and asked her in a hoarse voice to run down to Roháneks on the corner to buy some thread. She had decided to take up sewing again. She had made things for Martin and Josel when they were little. Those had been ‘troubled times’, too.

At the table, Mr Tausendgeld was all eyes and ears.

‘She must think she’s back in Prague,’ he said, smiling almost approvingly through the growths on his face.

It soon became clear that he knew ‘everything worth knowing’ about Maman and her illness. Mrs Schulz, he said, was a person of the highest rank who must be saved at any price. And as if this were something that could only be divulged in the greatest confidence, he leant forward and whispered to Professor Schulz that the Secretariat was in the process of setting up a special enclosed camp for all those enjoying the authorities’ protection. The camp would be opposite the now evacuated hospital in Łagiewnicka Street. The move there would be carried out under the protection of the ghetto’s own forces, under the command of Dawid Gertler himself, whom they had to thank for the successful negotiation of this unique agreement with the German authorities.

What does it cost?

was all Professor Schulz said; and Mr Tausendgeld – without hesitation, without even looking up from his paper, where he had already noted down the sum in the margin – replied:

Thirty thousand! They are demanding even more for what might be called notables, but in your family’s case I think thirty thousand marks will do.

Vĕra had often seen her father’s face turn pale with anger, seen the knotted veins on the back of his hand bulge as if they were about to burst. But this time, Professor Schulz managed to keep his anger in check. Maybe it was because of Maman’s confused voice, which persisted in calling out to Vĕra from the cubbyhole. Her illness hung like an incomprehensible punctuation mark in the thick, stuffy air above their heads. Or was the situation, as Vĕra would subsequently write in her diary, so absurd that it could be understood

only by acknowledging that the whole world had gone mad

?

In actual fact, Vĕra realised later, Professor Schulz had already made up his mind. They would wall up the opening to Maman’s room. Martin had an idea for what he called

false wallpaper

: an ordinary roll of wallpaper, glued to a wooden board and slotted into the tongue-and-groove wall, over the opening beside the kitchen sink. The side of the false wall could be prised up with a knife and moved aside, then slotted back in place. This wouldn’t put Maman’s health at risk, because the air vent was still there in the ceiling, and since Papa was a doctor, he would be able to get a

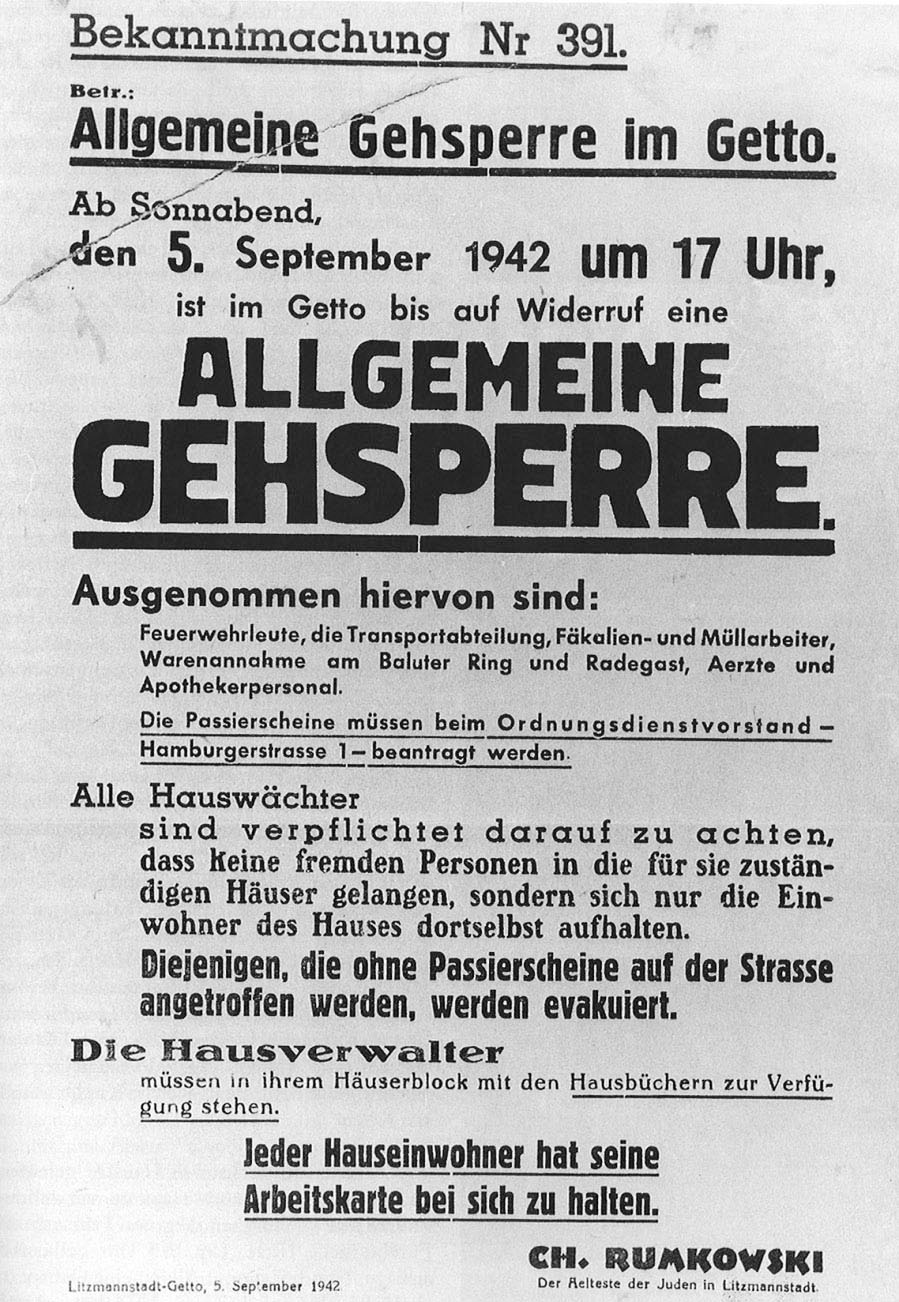

Passierschein

and come and go as he wanted, no matter what happened.

‘It’ll be all right, Vĕra, you’ll see,’ he said.

She wondered where he got it from, this unwavering conviction of his.

But it all had to be done quickly. The new Resettlement Commission had almost finished going through its lists of those required to come forward as replacements for the people who had been ‘redeemed’, and the Sonder were already going round looking for them in factories and living quarters.

On the afternoon of the third day of the operation, the Chairman had a new proclamation put up outside the Department of Statisitics in Kirchplatz. From now on, it said, the recruitment section at the Central Labour Office would also accept applications from children

aged nine and up

.

That could only mean one thing:

all children under nine were also to be deported!

The mad chasing around began all over again. Not to the hospitals and clinics this time, but to the Central Labour Office in Bałuty Square, where people queued for hours to get their children registered for work before it was too late.

Everyone was asking for the Chairman.

Where is the Praeses in this hour of need when we can least do without him? Tomorrow, they were told, tomorrow, in the fire-station yard in Lutomierska Street, he will make a speech to the residents of the ghetto that will answer all your questions.

*

In the early evening, Vĕra went into Maman’s little room one last time. Maman was talking about the Hoffmann family, who had been their neighbours all those years in Mánesova Street.

We’re in Łódź, Mama, not in Prague

, Vĕra said. But her mother went on insisting. Night after night she could hear their youngest girl walking up and down the hall outside the sealed apartment, crying for her deported parents.

Vĕra brought in the bedpan and fed Maman pieces of bread soaked in water. After a little while, Martin and Josel also squeezed in beside her. By then, even Maman realised things were not as usual. Her eyes went from one child to the next, with a glassy, unsteady look. Arnošt gave her the injection, in one arm, and her head fell into his hands like a rag. Then Martin and Josel walled her in. Arnošt had already prepared a death certificate. He said the best thing would be not to think of Maman as a living person, at least not for the next few, critical days.

But Vĕra could not stop hearing her heart beating behind the closed-up wall. That night, and on all those that followed, it was as if not just the wall but the whole room where they lay was bulging and pulsating with Maman’s invisible heartbeats.

On the afternoon of 3 September 1942, the authorities summoned the Praeses again. He stood before them as usual, head bowed, hands at his sides.

He faced Biebow, Czarnulla, Fuchs and Ribbe.

Biebow said he had given careful consideration to the Chairman’s suggestion that the old and the sick would be let go if the children were spared.

There is, of course, a certain logic to your proposal, Rumkowski, but the orders we have received from Berlin leave us no room for such an accommodation. All ghetto inhabitants who cannot support themselves must, of necessity, leave. That is the order, and it also applies to children.

Then Biebow set out a number of calculations he had asked to be made, and said these showed there should be a total of at least twenty thousand non-workers, the majority of them old people and children. If they could free themselves of these

Unbrauchbare

, Berlin would no longer find reason to involve itself in ‘internal’ ghetto affairs.

Rumkowski replied that this was an order no human being could carry out. No human being voluntarily gives up his own children.

Then Biebow replied that Rumkowski had had his chance but he had missed it.

You’ve had weeks, months, Rumkowski, but what have you achieved? You’ve taken every opportunity to get round the rules. You’ve set children to work who scarcely know what hemstitch is. You’ve turned the hospitals into rest homes . . . ! And all this has been going on while our administration does everything in its power to secure the ghetto’s food supply.

Then Fuchs said:

You must consider the nature of our heroic war effort, Herr Rumkowski. Everyone is called upon to make sacrifices.

Then Ribbe said:

What could possibly make you imagine we would expend time and energy on support for miserable Jews at a time when Germans are being forced out of house and home by the Allies’ cowardly air raids? Are you really so naive that you thought we would continue dispensing this sort of charity indefinitely, Rumkowski?

Rumkowski asked them to give him time to think it over and consult his colleagues. They said there was no time. They said that if he had not handed over comprehensive lists of ghetto residents over sixty-five and under ten within twelve hours, they would initiate the operation themselves.

Czarnulla said:

The ghetto is a plague zone, a boil that must be lanced.

If you do it now, once and for all, you may hope to survive.

If you don’t, there’s not a chance.

The public meeting in the fire-station yard in Lutomierska Street is due to start at half past three in the afternoon, but people have been gathering in the big, open space since two. At that time of the afternoon, the sun is at its highest, and the whole expanse of stone between the buildings on either side of the yard is turned into a well of scalding hot, white light. Only later in the afternoon does a narrow shadow start to edge from the long row of sheds and outbuildings running along the exterior of the crumbling stone wall. Those just arriving all cluster in the thin strip of shade. In the end there are so many of them jostling together along the wall that the chief of the ghetto fire brigade, Mr Kaufmann, feels impelled to emerge from his cool office and push or pleadingly pull on reluctant arms to make the crowd space itself out a little.

But nobody willingly stands in the broiling hot sun.

When the Chairman finally arrives, it is half past four and the area of shade has spread halfway across the inner courtyard. But it is by now such a huge gathering that only a fraction can stand in that shade. The rest have either moved to the gable end, deeper into the courtyard, or climbed onto the roofs of the sheds and outhouses. The people up on the roofs are the first to catch sight of the Chairman and his bodyguards.

At the sight of the old man, a ripple runs through the crowd. He does not walk with head and stick held defiantly high as usual, but with hunched shoulders and eyes on the ground. In an instant, the yard falls completely silent. It is so quiet that you can even hear the birds chirruping in the trees on the other side of the wall.

The podium this time consists of a rickety table. On top of that, somebody has placed a chair, so the speaker can at least be a head taller than the crowd. Dawid Warszawski is the first to climb up onto the improvised platform. The microphones have been mounted a little too far forward, so he has to stretch to reach them, which makes him look as if he is permanently about to lose his balance and fall off. Even so, somehow he gets too close to the microphone, and every word he speaks sends an echo billowing back and forth between the loudspeakers, as if it were constantly trying to interrupt him.

Warszawski says how ironic it is that the Chairman, of all people, has been forced to take this difficult decision. After all the years the Eldest of the ghetto has devoted to bringing up the Jewish children. (

CHILDREN!

The echo reverberates back off the walls.) In conclusion, he tries to appeal for the understanding of all those gathered to listen.

There is a war on. Every day, the air-raid sirens whine above our heads. Everyone has to run for cover. At times like these, the young and the old just get in the way. That it is why it would be better if they were removed.

After these words, which merely generate restlessness and anxiety in the crowd, the Chairman climbs onto the table and leans forward to the microphone. By his voice, too, people can tell that he has changed. Gone is the shrill, slightly hysterical tone of command. The sentences follow each other slowly, with a dull and sustained metallic tone; as if it were a torture to produce each word:

The ghetto has been dealt a terrible blow. They demand that we give them the very things most valuable to us – our children and our old people. I have never had the good fortune to father children of my own, but I have spent the best years of my life among children. So I would never have imagined that it would be I who was obliged to take the sacrificial lambs to the altar. But in the autumn of my years, I must now reach out my hands and ask:

Brothers and sisters, give them to me. Give me your children . . . !

[. . .]

I had a premonition of this. I was expecting ‘something’, and was constantly on my guard to try to prevent it. But I was unable to intervene, because I did not know the nature of the threat we were about to face.

When they seized the patients from the hospitals, it took me completely by surprise. Believe me. I had friends and relations of my own in those hospitals and I could not help them. I believed what happened there meant it was all over, and now we would have the calm I had worked so hard to achieve. But fate proved to have something else in store. That is the lot of the Jews: when we suffer, we are forced to suffer still more – especially in times of crisis like these.

Yesterday I was ordered to deport more than twenty thousand people from the ghetto; otherwise, they said, they would do it themselves. The question was whether we should take on this odious task ourselves or leave it to others. But since our guiding principle is not ‘How many will disappear?’ but ‘How many can we save?’, we decided – we: that is to say, my closest colleagues and I – that however hard it might be, we had to implement the ruling ourselves. I had to carry out the cruel and bloody operation myself. I had to amputate the arms to save the body. I had to let the children go. If I did not do it, then maybe yet more would have to go –

I have no words of consolation to offer you today. Nor have I come to try to calm your fears. I have come like a thief, to take from you what you hold dearest. I did everything in my power to make the authorities retract this order. When that did not work, I tried to make them reduce their demand. I tried to save at least one more age group – children between nine and ten. But they refused to yield. There was only one thing I managed to do. Children above ten are saved. Let that at least be some consolation in your great pain.

We have many tuberculosis patients in the ghetto; their days, or at best weeks, are numbered. I do not know – perhaps this is just a wicked and malicious thought, perhaps not – but I still cannot help putting it before you. Give me these patients, and I will be able to save healthy people in their place. I know how much it means to you to nurse your sick relatives at home.

But when faced with a decree that makes us choose who can be saved and who cannot, common sense dictates that the saved must be those who can be saved and those who have a chance of being rescued, not those who cannot be saved in any case . . .

We live in a ghetto. We live in such destitution that we haven’t enough to provide for the well, let alone the sick. We all care for our sick at the cost of our own health. You give them what little bread and sugar you can spare, but in doing that, you make yourselves ill. If I had been forced to choose between sacrificing the sick, those who can never recover from their illnesses, and saving the well, I would choose without hesitation to save the well. That is why I have ordered my doctors to surrender the incurably ill, with the aim of saving in their place healthy people who are still capable of living . . .

I understand you, mothers. I see your tears. And I hear your hearts pounding, you fathers, who will have to go to your work the morning after I have taken your children from you, those children you were playing with just the other day. I understand and feel all this. Since 4 p.m. yesterday, when this ruling was announced, I have been a broken and tormented man. I share your powerlessness and feel your pain; I do not know how I can go on living after all this. I must tell you a secret. Initially they demanded I sacrifice twenty-four thousand, three thousand people a day for eight days, but I managed to negotiate the number down to twenty thousand or less, on condition this would include children up to the age of ten. Children who have turned ten are out of danger. Since the number of children and old people combined amounts to thirteen thousand, the rest of the quota must be filled with the sick.

I find it hard to speak. My strength fails me. But I must ask you one last thing. Help me to carry out this operation. The prospect of them – God forbid! – taking the matter into their own hands makes me quake with terror . . .

It is a broken man you see before you. Do not envy me. This is the most difficult decision I have ever had to make. I raise my trembling hands and implore you: give me these sacrificial victims in order that I may save others from being sacrificed, in order that I may save a hundred thousand Jews.

That was what they promised me, you see: if you hand over these people yourselves, you will be left in peace –

(Shouts from down in the crowd:

‘We can all go’; and:

‘Mr Chairman, don’t take all the children; take one child from families with several!’)

But my dear people – these are all just hollow phrases. I cannot discuss it with you. When the authorities come, none of you will say so much as a word.

I know what it means to tear limbs from your body. I begged them on my knees, but it was pointless. From towns that formerly had seven or eight thousand Jews, barely a thousand reached our ghetto alive. So what is best? What do you want? For us to let eight or nine thousand people live, or look on mutely as all perish . . . Decide for yourselves. It is my duty to try to help as many survive as possible. I am not appealing to the hotheads among you. I am appealing to people who can still listen to reason. I have done, and will continue to do, everything in my power to keep weapons off our streets and avoid bloodshed . . . The ruling could not be overturned, only tempered.

It takes the heart of a thief to demand what I demand of you now. But put yourselves in my shoes. Think logically, and draw your own conclusions. I cannot act in any way other than I do, since the number of people I can save this way far exceeds the number I have to let go . . .