The Egypt Code (17 page)

Authors: Robert Bauval

To be fair, Egyptologists do not deny that the ancient Egyptians carefully observed and recorded the movement of the stars and probably portioned the solar year into twelve parts or ‘months’ even as early as the third millennium BC.

45

But in the same breath they do deny that the Egyptians were capable of recognising in these portions or constellations the figures of the creatures in the way the Greeks or Babylonians did. This stands in total contradiction, however, not only of the accounts of Herodotus and others, but also of contemporary archaeological evidence. For there exist drawings of ancient Egyptian cosmology showing human as well as animal figures that quite clearly represent constellations, such as Orion as Osiris, Canis Major as Isis, the Plough as a bull’s thigh, Draco as a pregnant hippopotamus, and so on. Egyptologists will be quick to point out that these constellations are not zodiacal ones, i.e. they are not the twelve through which the sun passes in the course of the year. True. But also shown in the astronomical drawings from the ceilings of royal tombs dating from the Ramesside period are animal figures that are clearly zodiacal, such as a scorpion, a lion and a ram. And there is, of course, the cosmic scales which Maat personifies. Such clear evidence has on occasion brought protestation by more open-minded historians of science, such as the eminent Russian astronomer Alexander Gurshtein, for whom it was obvious that the ‘ancient Egyptians were devoted to astronomy. They created the world’s first practical solar calendar. It demanded the measuring of the positions of the sun on the starry background, i.e. to recognise the zodiac.’ There is also the British Egyptologist Richard Wilkinson, who, as we have seen, was among the first in his profession to admit that ‘the stellar constellation now known as Leo was also recognised by the Egyptians as being in the form of a recumbent lion’ and that this ‘constellation was directly associated with the sun god’. To this we can also add the professional views of other scholars such as Yale University Egyptologist Virginia Lee Davis, who, in reference to the star-studded recumbent lion seen in Ramesside astronomical ceilings, asserted that ‘the Lion with its outline of stars must be Leo’,

46

and American scholar Donald Etz who made the same assertion in an article for the

Journal of the American Research Centre in Egypt

.

47

Even more recently, in 2001, the Spanish astronomer Juan A. Belmonte presented similar cogent evidence to the SEAC 9th Conference in Stockholm, where he informed his colleagues that ‘the Analysis of the astronomical data presented in the diagonal Ramesside Clocks has allowed us to prepare a potential list of correlations between the Egyptian stars presented in them and the actual stars in the sky. Some results are very coherent, such as the identification of . . . the Lion with our constellation Leo.’ Belmonte also showed that ‘the identification of the Lion (in the Ramesside clock) with our Leo and the lion in the ceiling representations’ are one and the same. At any rate, we needn’t get too entangled in this never-ending scholarly debate about the zodiac. What should really concern us is not whether the whole zodiac concept was known to the ancient Egyptians, but whether they saw in the pattern of the stars that we call Leo the same leonine figure we see, namely a recumbent lion; and, if so, whether or not they called this image Horakhti.

45

But in the same breath they do deny that the Egyptians were capable of recognising in these portions or constellations the figures of the creatures in the way the Greeks or Babylonians did. This stands in total contradiction, however, not only of the accounts of Herodotus and others, but also of contemporary archaeological evidence. For there exist drawings of ancient Egyptian cosmology showing human as well as animal figures that quite clearly represent constellations, such as Orion as Osiris, Canis Major as Isis, the Plough as a bull’s thigh, Draco as a pregnant hippopotamus, and so on. Egyptologists will be quick to point out that these constellations are not zodiacal ones, i.e. they are not the twelve through which the sun passes in the course of the year. True. But also shown in the astronomical drawings from the ceilings of royal tombs dating from the Ramesside period are animal figures that are clearly zodiacal, such as a scorpion, a lion and a ram. And there is, of course, the cosmic scales which Maat personifies. Such clear evidence has on occasion brought protestation by more open-minded historians of science, such as the eminent Russian astronomer Alexander Gurshtein, for whom it was obvious that the ‘ancient Egyptians were devoted to astronomy. They created the world’s first practical solar calendar. It demanded the measuring of the positions of the sun on the starry background, i.e. to recognise the zodiac.’ There is also the British Egyptologist Richard Wilkinson, who, as we have seen, was among the first in his profession to admit that ‘the stellar constellation now known as Leo was also recognised by the Egyptians as being in the form of a recumbent lion’ and that this ‘constellation was directly associated with the sun god’. To this we can also add the professional views of other scholars such as Yale University Egyptologist Virginia Lee Davis, who, in reference to the star-studded recumbent lion seen in Ramesside astronomical ceilings, asserted that ‘the Lion with its outline of stars must be Leo’,

46

and American scholar Donald Etz who made the same assertion in an article for the

Journal of the American Research Centre in Egypt

.

47

Even more recently, in 2001, the Spanish astronomer Juan A. Belmonte presented similar cogent evidence to the SEAC 9th Conference in Stockholm, where he informed his colleagues that ‘the Analysis of the astronomical data presented in the diagonal Ramesside Clocks has allowed us to prepare a potential list of correlations between the Egyptian stars presented in them and the actual stars in the sky. Some results are very coherent, such as the identification of . . . the Lion with our constellation Leo.’ Belmonte also showed that ‘the identification of the Lion (in the Ramesside clock) with our Leo and the lion in the ceiling representations’ are one and the same. At any rate, we needn’t get too entangled in this never-ending scholarly debate about the zodiac. What should really concern us is not whether the whole zodiac concept was known to the ancient Egyptians, but whether they saw in the pattern of the stars that we call Leo the same leonine figure we see, namely a recumbent lion; and, if so, whether or not they called this image Horakhti.

Let us, therefore, now focus our attention on this issue alone.

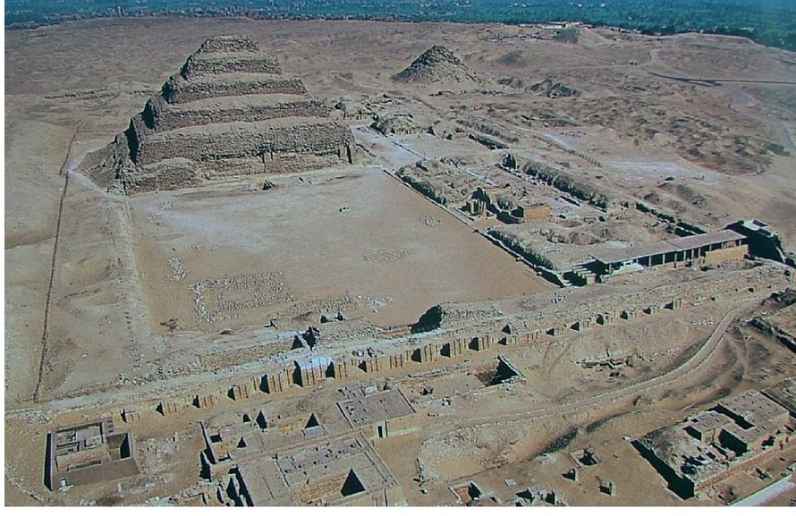

The Step Pyramid Complex at Saqqara.

The Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara.

Details of panelled boundary wall of the Step Pyramid Complex at Saqqara.

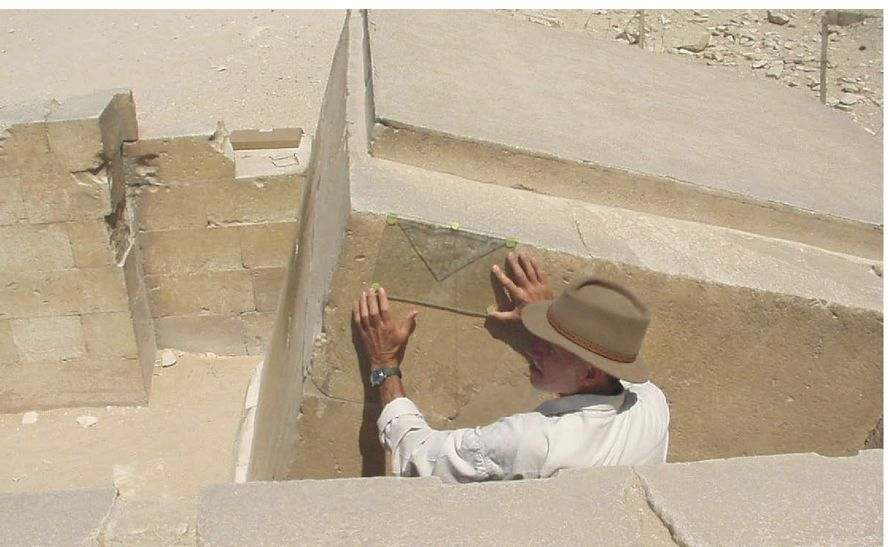

Robert Bauval measuring the inclination of the Serdab.

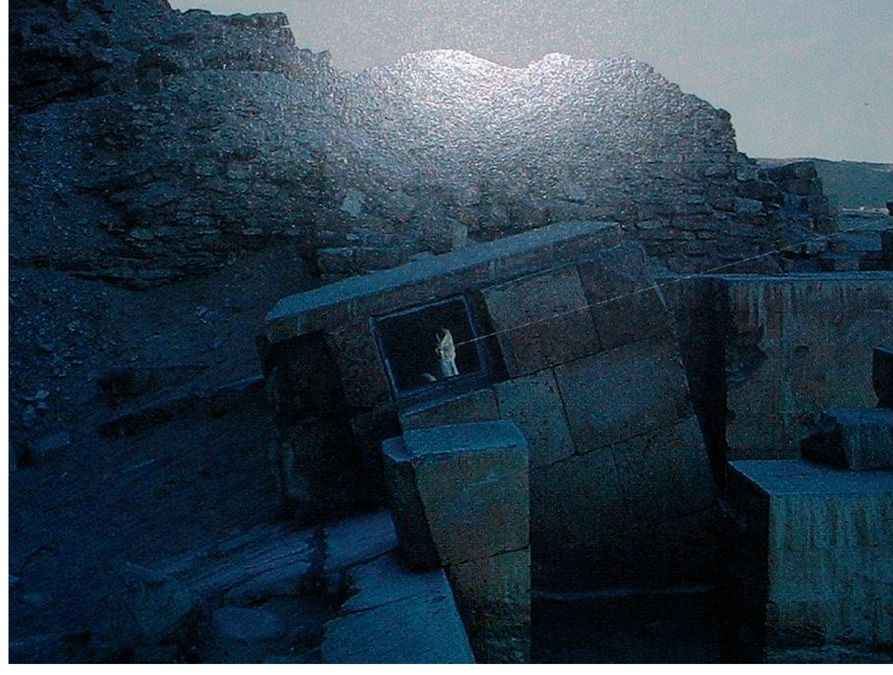

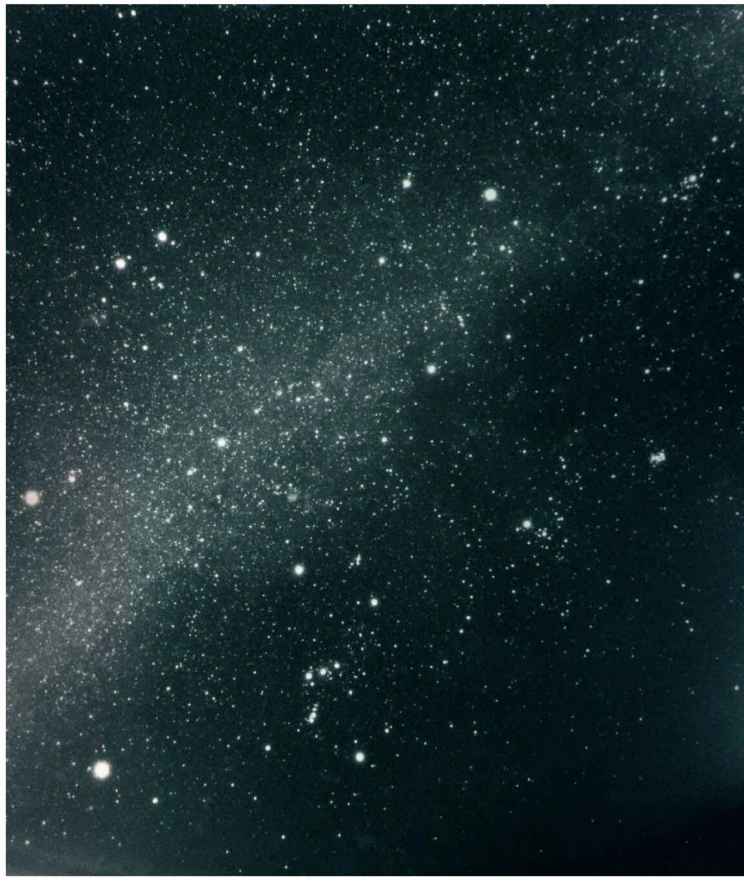

Night photograph of the Serdab with the statue of King Djoser gazing towards the circumpolar stars.

Looking through the peephole at the Statue of King Djoser in the Serdab at Saqqara.

The Giza Pyramids during the flood season.

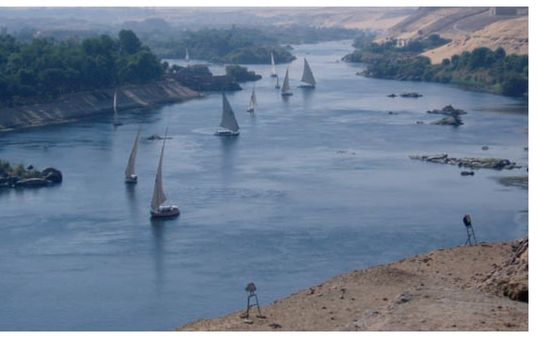

The Nile at Aswan during the flood season.

The solstices and equinoxes as seen in a flat desert landscape.

Other books

Surrender to Fire: Maison Chronicles, Book 3 by Skylar Kade

The Emperor Far Away by David Eimer

Thunderstrike in Syria by Nick Carter

Accent Hussy (It Had 2 B U) by V. Kelly

Black Jade by Kylie Chan

Mother of Ten by J. B. Rowley

Dark Celebration by Christine Feehan

Fates' Destiny by Bond, BD

To Pleasure a Lady by Nicole Jordan

Here Lies Arthur by Philip Reeve