The Educated Ape & other Wonders of the Worlds (8 page)

The interior of

the Terminal One building was wondrous to behold. Tiled throughout in faux

Islamic calligraphy, the walls were hung with mighty canvases depicting the

victories of Albion. Marble statuary of military heroes stood hither and yon,

along with busts of Queen Victoria in bronze and brass and gold. A kiosk

offered tea to the weary traveller. A branch of W H Smith was manned by

liveried servitors. The cash machine was sadly out of order.

Those

first-class passengers who had arrived upon the

Marie Lloyd

had long

since passed through the terminal building without needing to have their

passports stamped. They were, even now, being whisked away in luxurious

conveyances, bound in air-cooled comfort for their homes or hotels.

The

second-class passengers formed a queue.

And

this being England, the lady in black was ushered to the front of it.

A

chap in a cap of officialdom sat in a glass-sided booth, a narrow desk before

him, a rubber stamper upon this narrow desk. He appeared more interested in a

penny dreadful magazine that was positioned upon his knees than he was in his

duties and consequently did not look up as the lady in black placed her

passport on his narrow desk.

‘Nationality?’

he asked, without so much as raising an eyebrow.

‘British,’

the lady in black replied, her voice sweet but muffled by her veil.

‘Present

planet of occupancy?’ The chap in the cap could not really have cared much

less. He was far too preoccupied with the exciting adventures of Jack Union,

monster-hunter.

‘Mars,

Sector Six,’ said the lady.

‘Visa

then, please.’ And the chap in the cap stuck out his hand to receive one.

‘I

was not told that I would need a visa. I hold a British passport.’

The

chap in the cap let his penny dreadful slide from his knees to the floor. He

took up the lady’s passport and opened it before him.

‘Violet

Wond,’ he read aloud. ‘That is your name, is it? Violet Wond?’

‘Miss

Violet

Wond,’ said the lady in black.

‘And

your occupation? “Huntress”, it says here. What does that mean?’

‘It

means that I hunt. Game. Big game.

‘You

won’t find much of that here,’ said the chap in the cap. ‘Penge was once the

place for man-eating kiwi birds but the shaman shooed them all away.

‘I

hunt bigger game than that,’ replied the lady.

‘Do

you, now?’ The chap in the cap looked up. ‘Ah,’ said he, a-sighting of the

veil. ‘You will have to lift that, if you please, so I might check your face

against your photographic representation.’ He flicked idly through the lady’s

passport whilst he awaited revealment. ‘You do get about, do you not?’ said he

as he squinted at past rubber-stampings. ‘Jupiter, Mars, even Venus. But you

have not been here for some time, not since … eighteen eighty—nine! That is

nine years ago. Here a-hunting then, were you?’

‘Big

game, yes,’ said the lady as she slowly lifted her veil. ‘The biggest game,’

she whispered. ‘The biggest game of all.’

‘Africa,

then, was it?’ The chap in the cap smiled up at her.

‘Whitechapel,’

said the lady, her veil now fully raised.

‘Oh

my good God!’ croaked the chap in the cap, his eyeballs bulging from his head.

‘Why … you … are … But he said no more, for with that he fainted,

slipping from his chair and sinking upon his penny dreadful.

The

lady in black lowered her veil. She reached forward, took up the rubber stamp

from the narrow desk and applied it to her passport. Then she returned her

passport to her atramentous Gladstone and, jauntily swinging her parasol, she

tottered from Terminal One.

Within their

cupboard aboard the

Marie Lloyd,

the third—class passengers’ cries for

release grew fainter as their air supply ran out.

8

ressed

ressed

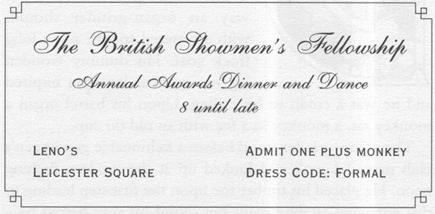

in a manner not unlike a pirate, the organ-grinder stood in Leicester Square.

It was eight of the evening clock and evening clocks were busily striking eight

around and about.

The

organ-grinder looked the way an organ-grinder should, with a battered tricorn

and a long frock coat. His dummy wooden leg was nothing less than inspired and

he was a credit to his calling. Upon his barrel organ a monkey sat, a monkey in

a fez with an old tin cup.

The

organ-grinder stood before a fashionable gentlemen’s club named Leno’s and

looked up at the modern flashing neon. He placed his timber toe upon the first

step leading to this esteemed establishment but found his way barred by a most

imposing fellow.

He

was a personage of considerable imposition, towering over six feet in height

and regally attired in robes and turban, as would be some eastern potentate. A

luxuriant beard, sewn with pearls and semi-precious stones, depended nearly to

his waist where a gorgeous purple cummerbund encircled him. Through this was

stuck one of those short Sikh swords that only Sikhs can remember the name of

He fixed the organ-grinder with an eye both dark and fierce and raised a mighty

hand before him.

‘You

cannot come in here looking like

that,’

he said in a commanding tone.

‘Away with you now before I summon a bobby.’

‘But

I have an invitation,’ complained the organ-grinder.

‘You

have

to let me in.’

The

subcontinental commissionaire, for such he appeared to be, extended his mighty

hand.

The

organ-grinder dug into a bedraggled pocket and produced a gilt-edged card,

which he handed up to the giant looming above.

The

commissionaire read this aloud in a booming baritone.

‘Ah,’

said the organ-grinder, a-grinding of his teeth. ‘Dress code

formal.

I

see.’

‘You

should have read the small print,’ said the beturbanned enforcer of sartorial

etiquette.

‘But

I am not to be blamed, for I have only the one eye, pleaded the organ-grinder,

and he pointed to an eyepatch which had received no previous mention.

‘Don’t

come the old soldier with me, please, sir. And anyway, I can tell that you are

not a

real

organ-grinder.’

‘What?’

The organ-grinder stepped back smartly and all but overbalanced on his dummy

wooden leg. ‘I have no idea what you mean,’ he said.

The

monkey looked up at his partner, and the monkey shook his head.

‘You

are William Stirling,’ said the enlightened commissionaire. Which came as

something of a surprise to man and monkey alike.

‘Oh,’

said Mr William Stirling, for it was indeed he and not some other organ-grinder

impersonator. How did you know it was me?’

‘Because

I shared diggings with you for three years, while you were at the Royal Academy

of Music studying to be a concert pianist and I was at RADA giving myself up to

the muse.

‘Kevin

Wilkinson?’ said Mr William Stirling, and the two shook hands. ‘Well, this is

quite a surprise.’

‘Certainly

fate has not been so kind to us as it clearly has to others,’ said Kevin. ‘I

might even now be treading the boards at Stratford, and you, dear boy, playing

Tchaikovsky before a rapt audience at the Albert Hall. But instead I must play

the part of commissionaire in turban and false beard, whilst you pose as an

organ-grinder.’

‘I

prefer the term

chevalier musique de la rue.’

‘And

well you might, dear boy. But regrettably I see a correctly attired gentleman

approaching and so must bid you

adieu.

Please take your leave or I will

be forced to strike you down with my kirpan.‘

[5]

William

Stirling slouched away, pushing his barrel organ.

‘Good evening,

sir,’ said the commissionaire who might once have played Hamlet. ‘Might I see

your invitation card?’

The

gentleman in top hat and tails, white tie and white silk gloves proffered said

card and smiled as it bore scrutiny.

His

monkey was similarly attired and looked very dashing indeed. His trousers had a

tail-snood made of silk.

‘Go

through please, sir,’ said the commissionaire, returning the gentleman’s card.

The man and the monkey ascended the steps and passed into the club.

‘You

tricked me,’ whispered the monkey to the man. ‘You had me believe that I should

wear the fez and shake the old tin cup this evening.’

‘Only

a good-natured jape, Darwin,’ the gentleman whispered in return. ‘And you look

wonderful tonight.’

‘And

don’t call me Darwin,’ whispered the ape. ‘I am now Humphrey Banana. Darwin was

my slave name.’

‘Darwin

is a most dignified name,’ said Mr Cameron Bell, for it was indeed he and none

other. ‘And you were never a slave, rather a respected servant of Lord

Brentford. Who, if you will recall, left his lands and fortune to you in his

will.’

Darwin

made grumbling sounds.

‘Which

you then gambled away,’ continued Mr Bell, ‘but have lately been able to

purchase once more with the wealth you have so far accrued from our

partnership.’

‘I

miss Lord Brentford.’ Darwin sighed a sigh.

Cameron

Bell glanced down.

‘I

wish he wasn’t dead,’ said the ape. ‘Perhaps he isn’t. Perhaps he swam ashore

somewhere after the

Empress of Mars

crashed into the sea and is now King

of the savages upon a cannibal isle.’

Cameron

Bell shrugged his shoulders at this. ‘I suppose that is possible,’ said he.

Then: ‘I wonder how exactly

this

works,’ and he worried at the Automated

Cloakroom System, a series of lockable boxes into which a gentleman might

place his hat and gloves, thereafter to watch his chosen lockable box whirl

away upon a jointed conveyor system into some far-away place in the gentlemen’s

club. ‘I think I will carry my hat with me, in case we have to take our leave

in haste.’

‘Are

you expecting some kind of trouble?’ Darwin asked.

Cameron

Bell shrugged his shoulders a second time. ‘This is an awards dinner,’ he said,

‘and things can become a tad unruly at such events.’

Darwin

was about to ask why, but Mr Bell shushed him to silence. A liveried servant

was approaching to guide them to their table.

‘If

sir and his pet would kindly follow me.

Darwin

bared his teeth at this. Mr Bell did rollings of the eyes.

The

dining room was suitably grand, with many marble pillars and alcoves where the

bronze busts of eminent club members stood, to be respectfully admired. Once a

year, the British Showmen’s Fellowship hired this room for their special dinner

to honour the achievements of the organ-grinding fraternity. It was a most

exclusive event and although Mr Bell had. managed to forge an invitation card,

finding a seat at the numbered tables might prove problematic.

‘Name?’

asked the liveried servant.

‘William

Stirling,’ said Cameron Bell, who had. been close enough to catch the name of

the piratically inclined ex-student of the Royal Academy of Music, who had,

most conveniently, failed to gain entrance here.