The Edge (3 page)

Authors: Clare Curzon

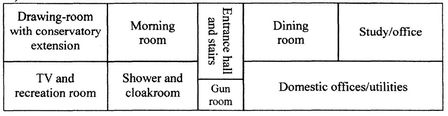

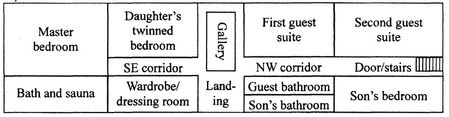

He drew in the rooms for each, naming them as he did so. Several officers in the elbow-to-elbow crowded room juggled with paper and pen, trying to keep up.

Â

FORDHAM MANOR

A) Ground floor

B) First floor

C) Top floor

Two unused staff dormitories, housekeeper's suite, bathroom, darkroom, laundry, box room

Yeadings nodded. Beaumont had acquitted himself well, now scowling impatiently while his audience's muttering covered efforts to reproduce his freehand sketch. In retrieving a dropped

pencil one constable slid off the edge of a shared seat. A muted cheer from others at the back faltered and was covered by the shuffling of heavy patrol boots.

pencil one constable slid off the edge of a shared seat. A muted cheer from others at the back faltered and was covered by the shuffling of heavy patrol boots.

Yeadings shared their sense of awkwardness. Even for the most case-hardened this investigation was nearly off the known scale. Little wonder the newer elements weren't at ease. He had trouble himself in confronting the callous and wholesale nature of the crime. For the present, emphasis would be on material evidence. Later, pressure must get worse as, with probing, the victims began to emerge as living, breathing souls. Some of the younger officers would resort to graveyard humour to get them through it.

âA restricted number of copies of this plan are for internal circulation only. Any leak to the press will be dealt with seriously,' Beaumont continued, grinding away.

M'm, Yeadings observed: a new ring of authority there. Did the DS have the energising scent of promotion in his nostrils? With Salmon's temporary shift to DCI, the need to replace a DI in Serious Crimes was more pressing. And overdue. So, would it fall to Beaumont or Rosemary Zyczynski? Both sergeants deserved it, were equally qualified, but he'd never get to keep either in his team once promoted to inspector.

He looked across to the door where Z had squeezed in as a latecomer. She caught his raised eyebrows and nodded back. Good, he thought. If the boy stayed missing, and nothing came of enquiries already under way, that photograph would have to be publicised. Risky, though, if the boy's survival left him at risk of a similar fate. Also tabloid press zest for the horrific could suggest guilty involvement, and only God knew what trouble that could bring on. Best wait a few hours more. Whether he proved a suspect or under threat himself, Daniel Hoad's whereabouts would be safer handled discreetly.

Salmon left the room, leaving Beaumont penned in by volunteers eager for plain-clothes secondment. Yeadings cut a swathe through and found Z waiting outside. âDaniel Hoad's photo is being copied,' she told him.

He nodded. âLet's go and see if it's hit my desk yet.'

It hadn't, but he didn't appear put out, making straight for the coffee machine on his windowsill and spooning in sufficient grounds for four. It had barely begun its gentle burbling when a civilian clerk arrived with a box file of 8x10s.

Yeadings studied the shot. In seven-eighths view, Daniel appeared relaxed, eyes slightly amused, his maize-coloured hair longish but well-cut, falling in softly waved wings beside sculpted cheekbones. âArty pose,' he gave as his opinion. âWhat do you make of him, Z?'

âAs they said, he looks older than sixteen. Good-looking. Quite the golden boy. Nice smile.'

âA charmer's smile, and he knows it's a winner. He's going to need all that assurance when he learns what's happened at home.'

He turned back to the window. âWe've heard only one opinion on him as yet. Ned Barton wrote him off as a “milksop” â perhaps because he doesn't soil his hands like a farm worker. I guess at this lad's age Ned was earning a third of a grown man's wage and helping support his parents. There's more than a generation's gap between them. Also the difference of wealth and education. This young man could be more complex than Ned gives him credit for.'

âIs there news of him yet?'

âOnly negative. The planned scout camp was wisely cancelled in advance of the storm, and the lads all dismissed an hour after they assembled. The scoutmaster interviewed suggested Daniel had gone home early with one of the other Explorer Scouts. He certainly wasn't there for roll-call. We're following up some addresses, to find out where he might have gone.'

Zyczynski slumped into a chair. âBut it's possible he did make for home. In which case, just what did he walk into? And where is he now?'

Even without police cases, Professor Littlejohn was accustomed to multiple post-mortems, due to the proximity of three motorways with the densest traffic flow in the South East. But this tragedy, a family group savagely slaughtered in their home, must give him special cause for pity. Yet the grey-bearded face bent over the first body showed no more than a frown of concentration, swiftly lightened by a gleam of curiosity.

He was taking them in order of age, the man first.

His assistant had shaved back the black, matted thatch of chest hair to reveal the long white scar of an incision for open heart surgery. âHe had that several years back,' Littlejohn decided. âThe pacemaker's a more recent job, quite a neat little Lucy Locket.'

Looking up, he caught Salmon's frown. âPocket, man! Use a little imagination.'

He wouldn't have been so brusque if the Boss had been there, Beaumont reflected. So Littlejohn, like Z and himself, wasn't particularly enamoured of the Acting DCI.

After the formal description of the body, he turned to the recent injuries.

âAha! As suspected, we have the entry wound for a bullet under all that stabbing.' He inserted a fine steel tube into the wound.

âA single shot aimed at an angle, upwards through the ribcage to above the heart, then deflected and â¦' He probed. â â¦and finally lodged in the right clavicle.'

He removed a small bullet. Z recognised a .22.

Littlejohn was muttering into his beard. âInteresting, that. One acknowledges, of course, the usual function of a pacemaker. But as a marksman's bull's eye, this is surely something else.'

âDead, just the same,' Beaumont murmured.

âAs you say. Certainly dead.' The pathologist's keen hearing had picked up the aside. âThe pacemaker's destruction would cause an immediate myocardial infarction. Since the single .22 bullet had been sufficient to kill him, the stabbings were mere ornamentation. Yes, comparatively little blood loss after the

initial spurt, but sufficient to disguise the bullet's entry point.'

initial spurt, but sufficient to disguise the bullet's entry point.'

He squinted over his half-moon spectacles in Salmon's direction. âAs well as the number of knife wounds, you will be wanting the precise angle of the lethal trajectory. And that will be interesting, because the victim is by no means a tall man. Five feet five inches, as my assistant has informed us.'

He beamed at the group of CID officers. âIt may make your task easier if among your suspects is a pygmy.'

âCouch potatoes are commoner,' Beaumont suggested. âThough murder's not a job to take on lying down.'

Zyczynski transferred her weight from one foot to the other. She could do without these tasteless quips. For distraction she moved a few paces away and turned her attention to the next body awaiting examination.

Jennifer Hoad, some three or four inches taller than her husband, had been of a slim build and long-boned; a classic fashion-model type. Agony had cruelly distorted a once-lovely face. She had long, shapely limbs and shoulder-length gold-blonde hair. Over torso and abdomen the network of blood had congealed in rivulets and pools in the hollows of clavicles and waist. She had been stabbed several times, probably while still standing, and again as she continued to bleed, lying on the straw bales, still alive. Not granted a quick death.

Z studied her face, the single vertical line chiselled between straight brows, the strong chin and jaw-line. This was a woman who had known her own mind and stood by it, authoritative and challenging. So what had drawn her into marriage with the small, dried-out, almost reptilian man who, more than anything, had reminded Z of a crouched brown toad? Yes, âToad', not Hoad, was probably the name other boys had called him at school.

Perhaps, alive, he'd had some special magnetism. A mellifluous voice? Great kindness? Whatever it had been, it was gone now and had left no record behind on his face. Not humour, she decided. Those heavy, dark-skinned features were never built for mirth. And Jennifer â what had made her smile? What sort of things could these two have laughed over together? In death it was unimaginable.

Z moved slowly on to the two smaller figures, but she found them less disturbing than she'd feared, so peacefully asleep, a white sheet drawn up to their shoulders, covering any injuries. Two school-friends as unalike as the two adults had been. The smaller one, Angela Hoad, was dark like her father, but had none of his heaviness. Instead she was elfin, in death the fine triangular face seeming almost to wear a puckish smile. The other child was harder to read, physically more developed but perhaps less aware of the world. In the way that children were drawn to each other at that age, she could have been the follower, a little slower, allowing the other to lead, perhaps cautioning when the Hoad child dared too far.

All of which supposition could be utterly wrong, Z warned herself; and went back to check on Littlejohn's progress.

The flesh had been given the Y-shaped main incision, the sternum was sawn through and the ribs opened out. Littlejohn removed the pacemaker in pieces, like a dismantled watch. There followed the ritual removal, examination, description and weighing of body parts, of little interest to the CID officers present, once the cause of death was established. But Salmon was impatient to know an estimated time of death.

He should have known better.

âThat will be revealed in the written report, after due consideration of all aspects,' Littlejohn was pleased to pontificate. âIf you find your presence here wearisome, Acting-Detective-Chief-Inspector, do feel at liberty to return to more germane matters, or at least release your minions for that purpose. An initial exploration of the four cadavers will require at least a further two hours of my time.'

Salmon's down-turned mouth tightened. Z watched a scarlet flush spread up his bull-like neck. âBeaumont, we can spare you,' he barked. âGet back and see what's turned up.'

âSir,' said the released DS with a nice balance of relief and distance.

Z watched him go with envy. For her the worst was surely yet to come.

Â

Â

Beaumont returned to base to catch Superintendent Yeadings, guiltily again at his coffeemaker. âShould really stick to decaff,' he admitted, âbut who's to know?'

âLike the expert I've just come from?' his DS dared warn.

âGod forbid â¦'

The internal phone on his desk interrupted them.

âGet that,' Yeadings ordered, waving a spoon in its direction.

âThey're connecting me with Swindon,' Beaumont murmured, the phone hugged between chin and chest while he reached across for a pen and paper. âYes, got that. Hang on, I'll ask him.

âSir, they've traced the absent housekeeper, staying at her aunt's. Are they to break the news to her?'

âNo. I warned them no action. This needs careful handling. I'll send Z down. You'd better get back to the post-mortem and relieve her. If Salmon objects, simply say “Women's work.” He'll like that.'

My, my, Beaumont told himself, preparing to leave, our Acting DCI seems to have needled everyone.

Â

Rosemary Zyczynski accepted her release without a flicker of expression. Out in the car park she punched a joyous fist in the air, remembered she was almost out of gas and pulled into the nearest service station for a refill.

The M4 was already buzzing with early rush-hour traffic, including heavy goods vehicles returning west and holding up streams of cars at the inevitable road works which that motorway seemed to spawn. Automatically she timed the journey and noted the trip-reading on arrival. Ninety-seven miles in an hour and forty-three minutes: not bad, considering.

Alma Pavitt's widowed aunt, Nora Bellinger, lived in a narrow, terraced house on the north side of the town centre. It was a typical Victorian development with a square, low-walled front garden barely large enough to hold an ancient bicycle, four slabs of paving stones and a few shrivelled survivals of autumn's chrysanthemums. The bike was a woman's, with a worn velvet pad to cushion the seat. A padlock and chain, attaching the machine to a staple fixed under the outer windowsill, was modest

warning of the neighbourhood crime statistic.

warning of the neighbourhood crime statistic.

It was the niece who opened to Z's knock. She leaned out to get the message with the door held close behind her, but failing to muffle the wailing of an older female voice from an inner room: âWho is it, dear? I don't buy from travelling salesmen. You can't be too careful.'

âSorry; what's that again? Did you say police?'

âMaybe I could come in and talk,' Z suggested, showing her warrant card.

Alma Pavitt examined it, appeared satisfied it was genuine, but looked slightly puzzled. âIs something wrong? I hope there's not a gas leak and you're wanting Auntie to move out. She's got a badly broken leg.'

âNo need to disturb her. Have you had trouble of that kind? Being evacuated, I mean.'

âA couple of months back there was a chemical fire and everyone had to leave for a couple of nights. She's still upset about it.'

âIt's nothing to do with her, except that we really need you back at Fordham Manor. Is it possible for you to return with me?'

âI was due back there tonight, but I haven't yet found anyone to relieve me here. Auntie's quite helpless, you see. I rang the Manor to get extended leave, but the storm must have brought the lines down. Is there much damage?'

By now Z had eased the woman into a retreat to the kitchen, from where they could still hear reproachful complaints from the front room and an insistent banging on floorboards.

âYou'd better sit down,' the DS advised. âI'm afraid the news is really bad.'

Alma Pavitt listened in growing horror, clutching at her throat with both hands. âOh my God, that's awful. Awful. I can't believe â¦'

While she partially recovered, Z made tea. Women's work, she thought, echoing the unknown words Yeadings had sardonically used of perhaps the most hated job that befell the police.

âUniversal panacea,' Alma Pavitt said wryly as she accepted her cup. âThank you. I'd better take Auntie's through and explain.

She'll never keep quiet otherwise.' Already she was displaying her practical side. Well, it wasn't as though the Hoads were family.

She'll never keep quiet otherwise.' Already she was displaying her practical side. Well, it wasn't as though the Hoads were family.

She was away some ten minutes. The seesawing of voices, hers low, the other a protesting wail, came wordlessly through the partition wall. Z used the interval to phone the local social services and explain the position. Even before Alma Pavitt returned, Z's mobile rang and a male voice assured her someone was already on the way.

âI doubt we can cover the old lady's care at home,' he said, âbut we'll try and get her into a hostel where they'll take good care of her. You can leave it with us, Sergeant. What a terrible business at Fordham. We heard about it on the midday news.'

Apparently these two women had not. Z commented on that when Alma Pavitt came back.

âAuntie won't have the news on. Not since Iraq,' she said. âI wasn't allowed to turn it on until

Neighbours.

She lives for that and

Coronation Street.'

Neighbours.

She lives for that and

Coronation Street.'

âI see.' Z explained about the arrangements social services were making.

âThe old dear won't like it one bit. Not at first. But it's better than anything I could have fixed up. I'd better go and pack a bag for her. We'll leave telling her until someone arrives. Meanwhile, could you go and have a word with her? She'll want to know the far end of everything that happened at the Manor. I'm afraid, now she's over the first shock, she'll have quite a morbid relish for details.'

Zyczynski managed to confine herself to the outline permitted to the press and quickly passed on to enquire about the circumstances of the broken leg. Mrs Bellinger, by now delighted with her visitor, was even more keen to share her own experience: a fall from her bike, no less, almost under the wheels of a panting juggernaut.

âI might have been killed,' she said proudly. âIt happened Friday about teatime, when the first shower started and the roads were all slithery. There's nothing wrong with my bike, as I told them at the hospital. The doctor said I didn't ought to be still riding the thing at my age, but I'm pretty fit otherwise. Just a

twinge or two of angina sometimes. Actually, more than riding, I mostly just push the bike and hang my shopping from the handlebars. It helps me get along. Only on Friday I was running late to go and pick up the laundry. Fridays they close early, you see.'

twinge or two of angina sometimes. Actually, more than riding, I mostly just push the bike and hang my shopping from the handlebars. It helps me get along. Only on Friday I was running late to go and pick up the laundry. Fridays they close early, you see.'

Z did, and stifled a sigh. âYou're lucky that your niece could drop everything and come to help.'

âOh, it was already arranged. She was coming anyway. Providential, you might say. Got me straight out of that awful hospital once they'd set the leg and done me plaster.'

News that she was again to be moved on roused frantic protests, but these quietened on the arrival of a briskly assured woman who was to see to everything and offered transport in an ambulance-type van with an electrically operated rear loading ramp. Auntie was trundled out importantly in a wheelchair on loan from the Red Cross.

Other books

Claire (Hart University Book 2) by Abigail Strom

Dear Stranger by Elise K. Ackers

Perfekt Balance (The Ære Saga Book 3) by S.T. Bende

The Libya Connection by Don Pendleton

Vados (Scifi Alien Romance) (The Ujal Book 1) by Erin Tate

Axel by Jessica Coulter Smith

Children of the Knight by Michael J. Bowler

Never Surrender (Task Force Eagle) by Vaughan, Susan

Lost Man's River by Peter Matthiessen

The Secret of the Soldier's Gold by Franklin W. Dixon