The Eastern Front 1914-1917 (19 page)

Read The Eastern Front 1914-1917 Online

Authors: Norman Stone

There was another strategic wrangle: If Ruzski wanted to go back, Ivanov and Alexeyev wanted to go forward. The two fronts had to act

jointly, for Ivanov could not advance in western Galicia without security on his northern flank, which only Ruzski could give; and that security could be obtained only if Ruzski stayed further forward than he intended. Ivanov made out that a final defeat of Austria-Hungary could be obtained. In November, he had worsted the Austrians in the Carpathians; he had advanced towards Cracow; and an Austro-Hungarian attack north of Cracow had broken down in unusually lamentable circumstances. Now, IX and IV Armies fought a frontal battle against mixed Austro-German forces north of Cracow, while the Russian III Army advanced steadily against Cracow from the east. He expected it to fall, and appointed Laiming, commander of Brest-Litovsk, to take charge of the siege. He summoned troops from the Carpathians to help out. If Ruzski went back, the Germans would threaten his northern flank; therefore Ruzski must stay where he was. Ruzski would not. A conference at Siedlce, his headquarters, failed to settle anything. In the event, enemy action settled things for him. German pressure led to a withdrawal from Lódz, early in December. In any case, the Austrians recovered. They sent troops south of Cracow, attacked the open flank of the Russian III Army, and Ivanov’s commander there mismanaged his reserves—one corps spending valuable time going back and forth over the Vistula. In the Carpathians, Russian withdrawals gave the Austrians superiority of numbers; and in these mountains, where flanking-operations could be conducted with relative ease, the Russian corps commander (Lesh) suffered one embarrassment after another. The emergence of Austro-Hungarian troops from the Carpathians threatened Ivanov’s southern flank, while Ruzski’s withdrawal in central Poland threatened his northern one. Ivanov withdrew towards the San, although Austrian pursuit was ineffective, such that, by the end of December, the forces were established on the Dunajec-Biala lines and in the central Carpathians.

11

Action in central Poland was similarly indecisive. The Germans launched a series of frontal offensives against the lines to which Ruzski had withdrawn, on the rivers Bzura and Rawka. They were an almost complete failure, in which IX Army lost 100,000 men. Some of the new corps, already hard-hit from the fighting in Flanders, were reduced to a few thousand rifles; munitions ran down, to the point where each gun could spend virtually only ten rounds daily. Ludendorff’s staff confessed, ‘It has to be said that the Russians have the advantage of the defensive, where they have always been good, and at that have a prepared field-position between the Vistula and the Pilica.’ Trenches were dug on both sides in central Poland, and by the end of the year a decision seemed as far-off as before.

Both sides never the less felt that some decision must be made. Already, there were alarms that neutral states would intervene—Romania, Bulgaria,

above all, Italy. The diplomatic equivalent of cavalry was a belief that the intervention of small states mattered—thus, for instance, George Clerk of the British Foreign Office: ‘If Bulgaria and Romania can be got in now it is the beginning of the end of the war’,

12

as if, in this battle of the Great Powers, a few ill-armed peasant divisions would make much difference either way. There was already talk of an Anglo-French expedition against Turkey, designed, in part, to bring in Greece and other Balkan states. Perhaps a resolute ‘push’ on the Russian side would be needed as well. On the other side, Conrad and Falkenhayn debated on how best to counter the threat of small states’ intervention, particularly, of course, Italian intervention. For the moment, events themselves did not push either side firmly towards one course of action, and there was much wrangling. Falkenhayn argued that the best course of action would be an assemblage of troops in the west: if France were beaten, the whole problem would cease to exist. Failing this, an expedition could be made against the Balkans. Conrad disliked this. He could not spare the troops, and in any case, after a further débâcle in December, felt that much more force would be needed than Falkenhayn offered. He believed that the neutrals would be deterred from intervening only if the Central Powers won a decisive success on the Russian Front. He was seriously alarmed for Przemyśl, the great fortress on the San, now blockaded by a Russian army. Its garrison of 120,000 men could not hold out longer than spring, as their supplies would not last longer—had even been depleted in October to maintain the troops that had relieved the fortress. The fall of Przemysl must be averted; and an offensive must therefore be made from the Carpathians. Falkenhayn disliked this scheme. He disliked still more a scheme of Ludendorff’s for a renewed offensive in the north. Germany had formed four new army corps, and Ludendorff wanted them for the eastern front. At the turn of the year, the Germans were more divided than before; but the politicians’ intervention proved decisive. Falkenhayn had failed to supply victory in France, and politicians felt that his policies should be abandoned.

His position was turned by Conrad and Ludendorff. Conrad made out, early in January, that his Carpathian position was going wrong; Ludendorff offered him two and a half infantry divisions and a cavalry division; Conrad then announced that he would use these for an offensive; Falkenhayn could do nothing against this, since the movement of reserves in the east was a matter for Ludendorff. But Conrad’s Carpathian offensive did not make much sense on its own; it would have to be supported by a parallel offensive, taking the other Russian flank in East Prussia—a point that Ludendorff did not fail to make. Yet that could not be staged without the four new corps. Falkenhayn gave way, by mid-January.

13

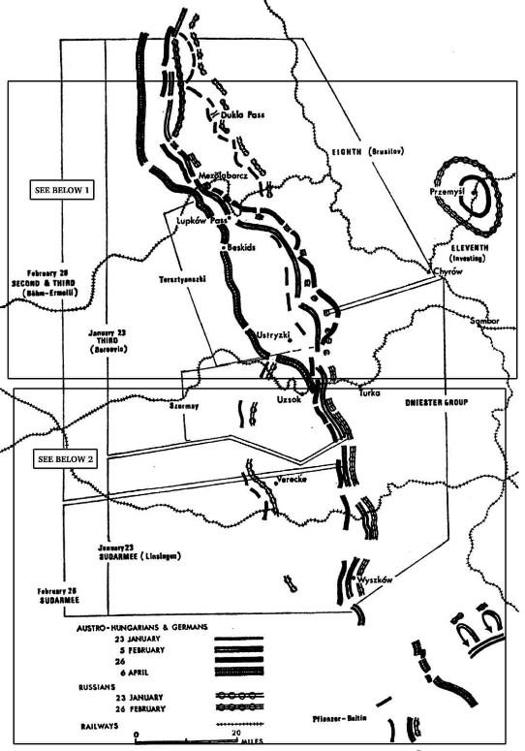

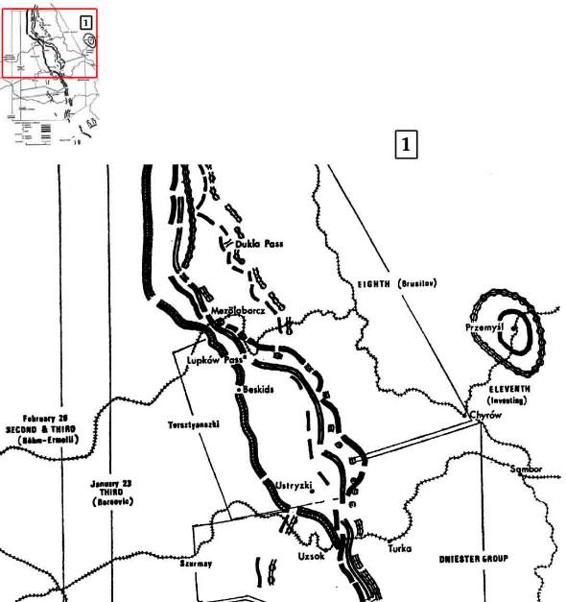

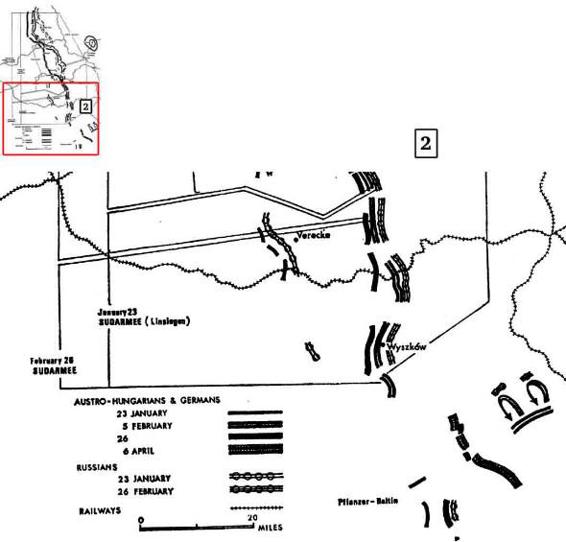

Conrad

The Carpathian battle, early 1915.

and Ludendorff had mystified him with the virtuosity of their interpretations—Austria-Hungary so weak as to need help; Austria-Hungary strong enough to make an offensive; the Austro-Hungarian offensive too weak to be left on its own; an East Prussian offensive thus emerging from these constructions—and Falkenhayn’s internal position was too unstable for much resistance to be made. In this way, the Central Powers were to be engaged in two offensives, for which they had not the strength. Conrad planned to use the German troops—joined with an equal number of Austrians to become

deutsche Südarmee

—in the middle Carpathians, with Austro-Hungarian armies to left and right, to re-take Przemyśl. Ludendorff would launch a parallel attack with VIII Army and the four new corps (X Army) from the Angerapp lines in East Prussia. Falkenhayn had faith in neither—particularly the Austro-Hungarian offensive. He complained to Conrad that the terrain and time of year were alike extremely unsuitable. He received a message to mind his own business, ‘to rely on my personal knowledge of the area’. The most that Falkenhayn could do was to attempt to saddle Ludendorff with responsibility, gazetting him as chief of staff to

Südarmee

. Ludendorff’s swollen reputation should be drowned in the Carpathian snows. At this, Hindenburg, at Ludendorff’s dictation, sent a letter offering to resign; and Falkenhayn drew back. It was, in the event, one of Falkenhayn’s protégés, Linsingen, with Stolzmann as chief of staff who took over

Südarmee

.

Similar confusions existed on the Russian side, the two fronts drawing apart. Ivanov and Alexeyev made out, as before, that decisive action on their front could produce a collapse of Austria, particularly of Hungary—‘she is ready to make a separate peace’. The Balkan states and Italy would be impressed; Przemyśl would fall. Ruzski and

Stavka

disagreed with this. In mid-January, Danilov and Ruzski between them, in secret, concocted a memorandum, arguing that the only place for an offensive was East Prussia. It was the Germans’ flanking-position in East Prussia that had made invasion of Germany impossible late in 1914—an analysis to which there was much foundation—and ‘You get the idea that energetic pressure here could throw the Germans back’.

14

An attack on the southern border of East Prussia ought to be made, by a new Army (XII); troops could be drawn into this from other parts of the front. There was certainly no sense in attacking again in central Poland, with what the Grand Duke described as ‘

toutes les horreurs

’ of German fortifications. An attack in the Carpathians would meet obstacles of climate and terrain. East Prussia was therefore indicated. This was not an analysis that the south-western command accepted. They first wanted troops for an offensive; then, as German troops arrived in the Carpathians, for a defensive action. They would not give up a man, insisted, on the contrary,

that they should be given troops. By 26th January Danilov had been persuaded to send them a corps from Ruzski’s front. At the same time, Ruzski went ahead with plans for his new offensive: the Guard and 4. Siberian Corps were due to arrive, and corps re-constituted after Tannenberg (13. and 15.) together with corps taken from X and I Armies could make up a substantial XII Army, to gather on the southern borders of East Prussia. In theory, this made a substantial force. But the Russians had divided themselves between two different operations, and were therefore unable to bring decisive force to either. Ivanov controlled, in the Carpathians, twenty-nine divisions, to which another two were attached when the fresh corps arrived. In the central plains of the Vistula, he had eighteen divisions (IV and IX Armies). Ruzski maintained seventeen and a half divisions in East Prussia, reduced to fifteen and a half when 22. Corps went off to the south-western front, and twenty-three and a half divisions (of I, II and V Armies) on the Bzura-Rawka positions and north of the lower Vistula. The Central Powers had eighty-three divisions to the Russians’ ninety-nine (with four to come); forty-one German and forty-two Austro-Hungarian. For the offensive to succeed, the entire Russian superiority should have been concentrated against East Prussia. But the demands of Ivanov made certain that this would not happen, and although, as Danilov had said, the shell-reserve per gun now reached over 450 rounds, and although the intake of new man-power was secured by entry of the 1914 class of recruits, these advantages were thrown away.

The campaign of 1915 opened with a characteristic episode. Ludendorff decided that there should be another attempt in the central plains of the Vistula; at the end of January IX Army attacked, near Bolimów, using gas: its first appearance in the war. The attack went wrong—gas blew back on the Germans, and the cold weather ensured that it would in any case be ineffective. The Germans were sensible enough to break off their attack when it failed. The Russians counter-attacked—using eleven divisions, under a single corps commander, the cavalryman Gurko. Command failed to keep in touch with troops; there was no coherent plan, little training, only a mad persistence. 40,000 men were knocked out in three days. Characteristically, failure was ascribed to the wrong reasons. The inappropriateness of the season, the lack of planning, the crazy over-loading of a single corps command—none was noted. Instead, Ruzski told Smirnov, the aged commander of II Army: ‘Victory on your front cannot fail, as you have eleven divisions on a front of only ten kilometres’. This was, in a sense, the very reason for failure—German artillery could concentrate on a very small area, enfilading it on one side. But Ruzski blamed ‘lack of resolution’, and Russian troops

were driven again and again into much the same pattern of attack—failures being blamed, first on cowardice, and then on lack of shell.

15