The Dulcimer Boy (7 page)

Authors: Tor Seidler

I

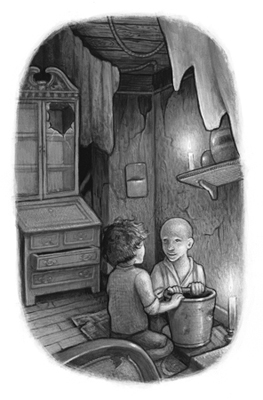

T WAS A LARGE

one-room shack with an oilcloth window and peeling wallpaper. Light was provided by a few old candles leaning crookedly on shelves, and a smoky, smoldering fire inside a wood stove. In the middle of the room Mr. Carbuncle sat in an easy chair, smoking a cheap cigar. Morris lay like a large fish on one of two cots against the back wall. In a corner, looking peculiarly out of place, stood the antique mahogany secretary, the glass missing from one of its doors.

After Mr. and Mrs. Carbuncle had asked William a few perfunctory questions about his long absence, they began ignoring him as if he

had never been gone. He sat on a threadbare rug in a corner, smiling at his brother, who was scrubbing rather futilely at the soot on his face and shaved skull. It was not a heartening sight, but at least he was alive.

His aunt began to make weary rounds of the room, flapping her apron in front of her. A dirty cloud of cigar smoke and smoke from the wood stove continued to hang below the ceiling, however. Her face grew more and more pinched. Finally, to William's surprise, she seized a newly lighted cigar out of her husband's mouth and tossed it into the bucket where Jules was washing.

William asked Jules about his hair. Jules turned to him with a melancholy look, still dumb.

“All it did was bring more soot into the house,” Mrs. Carbuncle answered for him.

William looked in silent anger from her to his uncle. Breathing in chimney soot all day could be nothing for Jules but a continuous

reminder of the ritual of the cigar smoke.

Jules turned to him with a melancholy look

Soon Mrs. Carbuncle sat down at a deal table by the stove and began pounding some unsavory-looking meat with a mallet.

“Where do you shop, Aunt Amelia?” William asked.

“The groceryâwhere do you think?”

“But I asked the grocer if he still delivered to you when I wasâ”

“Then you must have asked for the Carbuncles,” she said, giving the meat a sudden killing blow. “We've changed our names. We're the Joneses now.”

When she had put some potatoes on to boil, she came over and pulled the dulcimer out from under his astrakhan coat. She went over to her husband in the easy chair.

“Busy?” she said sarcastically.

“Why, no, Amelia, my dear.”

She thrust the instrument at the new Mr. Jones.

“Do you suppose you could manage to keep hold of that?”

“Of course, Amelia, my dear.”

“Morris, will you track down one of those street urchins? Have him go and tell the auctioneer to send down anyone interested in buying a dulcimer. Here's a dime.”

Morris lolled over and stared at his mother with a look of such doleful resentment that she finally gave a weary sigh and pulled on her galoshes.

As soon as she was gone, Mr. Jones had Jules fetch him a bottle of sweet wine from a wicker chest in a corner of the room. After a few drinks he began to tilt the dulcimer this way and that in the candlelight.

“Worth four or five hundred, if memory serves me.”

William made a sound of protest.

“More, was it?” said Mr. Jones. “Then I'll have to keep it in a particularly safe place, won't I?”

This place turned out to be his lap. When Mrs. Jones returned and served up dinner, William watched his uncle instead of eating. Mr. Jones used the dulcimer as a tray. Yellow drippings oozed near the rim of his plate. And when he had finished his dinner, he lit up a cheap cigar, flicking the ashes carelessly here and there.

When Mrs. Jones had done the dishes in the bucket, she sighed wearily, dried her red hands on her apron, then went around the room, blowing out the candles.

“You can sleep with your brother,” she said to William. “Jules, take out the garbage.”

Once again she snatched away her husband's cigar, proving that Mrs. Jones had retained no trace of Mrs. Carbuncle's servility toward the gentleman she had married. He leaned back in the chair without protest and closed his eyes to sleep. Morris, meanwhile, was already sound asleep, drool running out the corner of his mouth onto

his pillow. When Mrs. Jones had blown out the last candle, she collapsed on the vacant cot.

William lay waiting on the corner rug. It was some time before Jules came back in from taking out the garbage. The faint glow from the wood stove was dead, and the two boys lay together under the astrakhan coat in the dark.

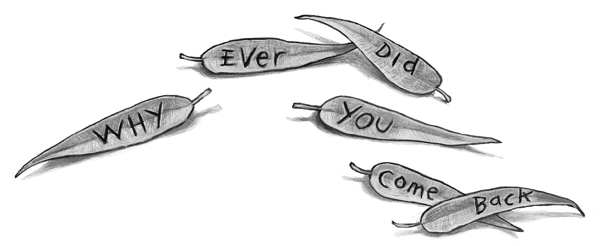

An hour later, when their aunt and uncle had started snoring, Jules lit a candle stub that was wedged in a little crack in the wall, where the flame wagged in a small draft. He then spread out some willow leaves he had apparently collected on the riverbank while taking out the garbage. He began scratching words into them with a nail:

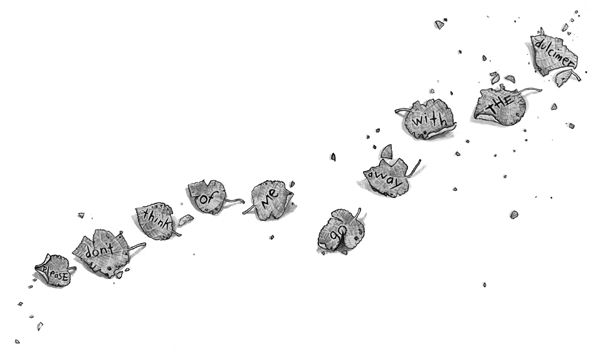

William looked curiously from the candlelit message to his brother's face. The answer was plain, but he dared not speak for fear of waking his aunt and uncle. He reached into the pocket of the astrakhan coat and brought out the old linden leaves. Although brittle, they were still legible. He arranged them for his brother.

Jules stared curiously at the candlelit leaves. He shook his head, and as he did, a few flecks of soot fell from his shaved skull. He rearranged the old brown leaves.

T

HE CANDLE FLAME

began to dance. The draft grew stronger, rustling the brittle leaves. They swirled together like playing cards being gathered up after a hand, then the candle went out.

The darkness seeped into William's soul. Although still conscious of his brother at his side, he felt alone. One of the old leaves blew against his hand. He picked it up in the dark, closing his hand around it. It disintegrated into a dry powder.

Mrs. Jones shook him awake. A mouse-colored light had crept in under the door of the

shack. The others were still asleep. She supplied him with a brush and bag and informed him that he was to learn chimney sweeping by cleaning out the stovepipe over the wood stove.

“Being small has some advantages,” she said. “You've got a couple hours before I'll have to be warming Morris's porridge.”

She opened the square cast-iron door and helped him into the stove, shutting the door behind him.

The bowels of the stove were in utter darkness. He felt around the foul bed of ashes, then groped overhead for the opening into the stovepipe. It was clogged. He took the handle of the brush and began to poke at it. Cakes of soot began to fall on him. The air began to taste like ashes; he choked. He beat his fist on the side of the stove. Then he collapsed in the heap of ashes.

He sputtered and opened his eyes. He was

lying on his back on the floor of the shack; Jules was pouring water on his face from the bucket. Mrs. Jones was standing over him, her arms crossed.

“How are you going to do chimneys if you can't even manage a little stovepipe?” she asked.

She turned to fixing breakfast. Jules pulled him back onto their corner rug and brought him a glass of water. William felt decidedly weak, but after drinking he could at least speak again.

“Uncle Eustace's pen,” he whispered.

While Mrs. Jones stirred porridge, Jules sneaked over to the mahogany secretary and slipped a pen out of the top drawer. He gave this to William, who then pulled out the card he had found in his hand the morning before. William reread it dubiously. It had an embossed crest on it, below which were scrawled the words:

If I can ever be the slightest use,

I beg of you to get in touch with

Below which, in embossed lettering:

Â

THE HONORABLE HENRY GILDENSTERN

MAYOR

THE CITY OF NEW YORK

Â

William took the pen and wrote on the back of the card:

Please come to the shack by the river in

Rigglemore, the one with the birds on the roof.

He slipped the card to Jules, telling him to give it to the grocer if he passed the grocery during the day.

“It probably won't come to anything, but his son goes all the way down there every couple of

weeks,” he said quietly, and then fell asleep on the rug.

Â

Inhaling the ashes made William ill for five days.

“Just what I needed,” Mrs. Jones said. “Another invalid.”

Lying on the corner rug, William watched his brother come in every evening, covered with soot, handing his aunt the money he had made. The loneliness he had felt upon realizing that his brother was not utterly dependent on him began to disperse. Late one night he leaned up on an elbow and looked at his sleeping brother's shaved skull. It was faintly illuminated in the light of the quarter moon coming through the oilcloth, and he contemplated it without feeling pity.

He recuperated. His aunt insisted he finish the stovepipe before going out on a real job. In

a leaf message Jules offered to do it for him late one night, but William refused. His next attempt, however, resulted in a relapse. He was ill for two more days.

Early on the morning of the third day he made yet another attempt, this time his aunt allowing the stove door to remain open for the sake of ventilation. He had worked his way about a foot up the clogged stovepipe when he heard the sound of horses in the lane outside. He crouched down into the stove itself, peering out the open grate.

There was a knock on the door of the shack. Mr. Jones, awakening with a start, shrank down in his easy chair.

“Someone we knew?” he said, horror-struck.

Mrs. Jones went and cracked open the door, letting a sheet of light into the dim room.

“Yes?”

“I'm looking for a Mr. Drake,” a man's voice said from outside.

“Drake? There's no Drake here.”

Mrs. Jones opened the door a little wider.

“The auctioneer didn't send you down to look at the dulcimer?”

“Dulcimer? You have a dulcimer?”

Pulling off her apron, Mrs. Jones opened the door all the way. A withered old gentleman hobbled in on a silver-headed cane.

Mr. Jones, struck by the man's respectable attire, got up from his chair.

“Good morning, my good sir. My name is Jones.”

“And you've never heard of Mr. Drake?” the old gentleman said, looking around the dim room. “This

is

the shack with the birds on the roof.”

“We come down here for the sport, every fall, to fish in the river,” said Mr. Jones. “Our

estate, of course, is on the hill above town.”

The old gentleman hobbled up and took the dulcimer from his hands. Mr. Jones smiled.

“A fine example, isn't it?”

“Indeed.”

“I believe it's valued in excess of six hundred dollars.”

“Oh, no. Far more than that.”

“More!” Mr. Jones contained himself. “My clumsy way of testing you.” He stroked his bald head. “Out of curiosity, what would you call a fair price?”

“Price? Do you play, Mr. Jones?”

“Good heavens, no!” he exclaimed with dignity.

“Nor I,” the old gentleman said sadly. “So in our hands I don't suppose it's worth much of anything.”

Mr. Jones echoed the alarming words: “Not worth much of anything?”

William, at this moment, squeezed himself out of the stove.

“Finished?” Mrs. Jones asked.

William shook his head. Soot sprinkled down onto the floor.

“Mr. Jones,” she said, “you're really going to have to do something about this mop of his.”

Mr. Jones eyed the thick mass of sooty curls, a just perceptible gleam of relish in his eye. William wiped some of the soot from around his eyes and looked at the guest uncertainly.

“You won't let them sell it, will you, Your Honor?” he ventured after a while.

“Uneducated,” said Mr. Jones. “Don't mind him calling you âYour Honor.' He doesn't know any better.”

“It's quite all right,” said the old gentleman. “Is the dulcimer yours, son?”

“It came with me, Your Honor. Me and

Jules.” William looked around and pointed into the corner. “That's Jules.”

You won't let them sell it, will you, Your Honor?

The old gentleman reached out curiously and touched William's face. He began to wipe some of the soot from the boy's cheeks and forehead. His old eyes widened. Suddenly he looked rather angry.

“But good heavens! You're the lad who played in the inn!”

William nodded.

“But how could you be so careless with your hands?”

William looked down at his hands, encrusted with soot.

“I'm sorry, Your Honor, I was sweeping the stovepipe.”

“Sweeping the stovepipe? With those hands?”

The old man had a surprisingly commanding voice, and as he spoke, Mrs. Jones shrank back a little toward the stove.

“Oh, are you responsible, madam? You have the good fortune, I take it, to be his mother.”

“Onlyâ¦only his aunt,” she said in a voice not at all piercing.

Mr. Jones, however, drew himself up with dignity.

“Just who, sir, do you think you are,” he demanded, “coming in here and cross-examining my household?”

The old gentleman gave him his card. As he read it, the pinkness drained from Mr. Jones's face. He stared aghast at the withered, distinguished features of the guest and then sank into his easy chair.

“You won't let them sell it, will you, Your Honor?” William said, repeating his original question.

“Have your aunt and uncle formally adopted you into the family?” asked the Mayor.

William shook his head.

“We're not real Carbuncles, Your Honor.”

“Then they haven't any claim on you.” The Mayor smiled. “That being the case, I don't suppose I could tempt you to make a trip to New York?”

“Your Honor?”

“Every year we give a series of free concerts, in different parts of the city, at different times of the year. The next is supposed to be the week before Christmas at the Opera House.” The Mayor laughed. “Of course, you wouldn't be on the free end of things. We would pay you, say, a thousand dollars.”

“A thousand dollars?” William looked inquiringly around the shack, from his cousin to his aunt to his uncle. “Don't you think that sounds like rather too much?” he asked them. “I mean, especially at Christmas?”

Morris was still sound asleep and made no reply. Mrs. Jones opened her mouth but was

now unable to raise her voice to so much as an audible level. Mr. Jones, shrunken down in his easy chair, stared off at the empty wicker chest in the corner of the room, muttering something about a golden opportunity.