The Drowning (21 page)

Authors: Valerie Mendes

Tags: #Teenage romance, #Young Adult, #love, #Joan Lingard, #Mystery, #coming of age, #Sarah Desse, #new Moon, #memoirs of a teenage amnesiac, #no turning back, #vampire, #stone cold, #teenage kicks, #Judy Blume, #boyfriend, #Twilight, #Cathy Cassidy, #teen, #ghost, #Chicken Soup For The Teenage Soul, #Family secrets, #Grace Dent, #Eclipse, #Sophie McKenzie, #lock and key, #haunted, #Robert Swindells, #Jenny Downham, #Clive Gifford, #dear nobody, #the truth about forever, #Friendship, #last chance, #Berlie Doherty, #Beverley Naidoo, #Gabrielle Zevin, #berfore I die, #Attic, #Sam Mendes, #Fathers, #Jack Canfield, #teenage rebellionteenage angst, #elsewhere, #Sarah Dessen, #Celia Rees, #the twelfth day of july, #Girl, #Teenage love

“Yes, Dad.” Jenna eyes burned. “But that was before—”

“That

was before . . . And

this

is afterwards.” He held out his arms. “Now, are you going to give your plumpish, frumpish old dad a hug or what?”

Jenna stood at the doorway to Lelant’s village hall. Inside she could hear the thunder of the CD music, Leah’s firm voice giving instructions above it.

“Use

the space. Take the risk. If you don’t, you’ll never know whether you can be an exciting dancer.”

She grinned to herself and pushed at the door.

Leah stopped dead in her tracks. “One moment,please, girls. We have a visitor.” She dived towards the CD player and turned it off. She held out her hands to Jenna, her eyes blazing with delight. “I can’t believe it . . . Are you a ghost?”

Jenna laughed. “Pinch me and see.”

“Have you come to dance?”

“Yes, please. Will you have me back?”

“So you’ve come to your senses at last . . . Does this mean what I hope it means?”

“It sure does,” Jenna said. “Now, can I go and get changed?”

“I haven’t sung a single note since Benjie . . . since he—”

Helen sat down at the piano. She looked up at Jenna, her eyes beneath her wild grey fringe bright and understanding. “You haven’t exactly had much to sing about.”

“No. It was like I kept saying to myself,‘Shut up. Pay the price. Forget who you really are. Get your head down and stay that way. ’ ”

“And now?”

“Now I feel a hundred years older, as if along the way I’ve forgotten how to be a teenager. But I’ve remembered who I am.” Jenna swallowed. “Could you help me find my singing voice again?”

Helen ran her hands over the keyboard.

Jenna began to sing.

As the notes flooded out of her body, out of her throat, she felt them change from a shout of hurt and pain into a song of renewal and of joy.

Christmas seemed to pass in a dream. After the holidays were over, Dad started asking around in the Cockleshell for new staff.

“I don’t need to advertise,” he said. “I know plenty of people who’d love to work here. I want two or three helpers, so I get a chance to see which one I work with best.”

“What about Hester?”

“She doesn’t want to come back full-time.” Dad blushed. “I couldn’t have a better friend . . . Friendships at my age are hard to come by. I don’t want to spoil it.” He stared sadly out of the window at the Digey as the winter streets darkened into night. “Anyway, my Lydia may still come back to me.” He turned to Jenna. “I can’t stop hoping, you know.”

“I’ll see her in London,” Jenna said. “It’ll be difficult, but I promise you we’ll meet. We’ll

try

to become friends.” She looked across at him. “Then I can let you know how she is.”

Dad’s face brightened. “If she ever needs anything, if she ever wants to see me—”

“Oh, Dad.” Impatience and anger and pity washed through her. “If Mum ever wants you, she knows where you are.”

“I’m trying not to think about being away from you,” Jenna said.

She and Meryn were spending her last evening together at his cottage.

“I just keep on telling myself I’ll be back in the holidays.”

“You may be back, but you’ll be different. You’ll be the Urdang’s student: devoted, dedicated, disciplined.”

Jenna laughed. “That makes me sound very stern and professional.”

“But you

will

be. It’s a tough life.”

Jenna looked up at him. “The tougher the better. The harder the challenge, the higher I shall jump. The more work I have, the less time there’ll be to brood about how much I’m missing you.”

“Will you phone me every week?”

“You know I will . . . Now, stop all this serious talk before I burst into tears and change my mind.”

“Don’t do that. I want this evening to be extra special.” He stroked her hair. “By the time Easter comes,we’ll both have changed. We may never be together in the same way again.”

“You’ll meet someone else.” Jenna stared into the fire, jealousy flicking at her heart. “Someone from St Ives who’ll be happy to stay here, who won’t go dashing off to chase her wild dreams.”

“And you,” Meryn said teasingly, “you’ll meet a dancer who’ll sweep you off your feet. Literally!”

“But the person who made me come to life again is you, Meryn.” Jenna blinked away the tears. “For that I love you – and I always will.”

On the station platform at St Erth, Dad took her in his arms.

“I’m so proud of you. I know what a fight you’ve had.”

“Take care of yourself, Dad. Promise me.”

“Be sure to get plenty of sleep. The first two weeks will be the worst. You won’t know what’s hit you.”

“And look after Dusty for me. I searched for him everywhere this morning. He probably didn’t want to say goodbye.”

“Tell that sister of mine she’s very lucky to have you!”

“I’ll be back for Easter. The time will fly.”

“Yes.” Dad released her. “Go on, then . . .”

“Love you, Dad.”

“Quick . . . Start the clock ticking . . . Get on that blooming train.”

In the room that would be her home for the next three years, Jenna unpacked her possessions. Clothes in the cupboard. Dance gear in the chest of drawers. Books on the shelf. Files in the desk.

On her bedside table she propped two photographs.

Dad and Benjie, laughing together on Porthgwidden Beach, sitting at one of the picnic tables on a Sunday afternoon, the wind flicking through their hair, Dad’s arm round Benjie’s shoulder.

Meryn, lean and bronzed in his grey-and-white tracksuit, standing outside the harbour cottage, his dark eyes smiling.

Next to them she placed something she had taken from Benjie’s room: the engine from his train set, graceful, solid, bottle-green.

At the Academy, their ballet teacher checked every name and face.

She said, “I’d like to extend a special welcome to our new student, Jenna Pascoe.”

Jenna blushed.

“Jenna was unable to join us last term. She knows she’ll have to work extra hard to catch up . . . I’m sure you’ll all help her and make her feel at home.”

The students murmured their welcome.

The teacher’s eyes scanned their bodies, picking up on every detail of how they stood, their poise, the eagerness in their eyes, their readiness.

“I hope you’ve all been exercising in the holidays . . . We can never afford to take time off . . . If we do, our bodies will complain and our work will suffer.

“Right . . . into the centre with you and down on to the floor . . .

“Fine . . . Spread out, use the space in the corners, there’s plenty of room . . .

“Piano, please . . . Thank you, Nick . . .

“Are you ready, Jenna?”

“Yes,” Jenna said firmly. “I’m ready.”

“Right, everyone . . .

“Shall we begin?”

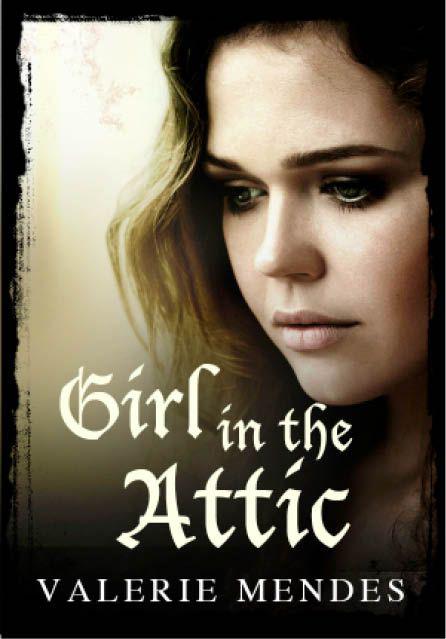

Girl in the Attic

. . .

Thirteen-year-old Nathan is furious when Mum hauls him off to Cornwall for Christmas and then tells him they are to move there for good. He knows he must accept the fact that his dad has left them to live with another woman, but he is desperate to be back with him in London. He has never been separated from his best friend, Tom, either. Life, it seems to him, has become intolerably unfair.

After a blazing row with his mum, Nathan runs away for the afternoon – only to discover, entirely by chance, a cottage, a garden by the sea, and an enchantingly beautiful girl who seems more miserable than he is himself.

The girl in the attic. Who is she, and what is the family secret that haunts her life?

Nathan suddenly realises that seeing the girl again and finding out about her have become an obsession. He lays a careful plan that enables him to return to the cottage, where he discovers her name – Rosalie – and that her problems put his own in the shade. He longs to help her. One night, alone in the attic, he is welcomed by the ghosts of Rosalie’s family, whose frail spirits and soft laughter stay with him in his dreams.

Nathan enlists the help of his grandfather, gradually managing to unearth some of the secrets that dominate Rosalie’s life and that of her bullying father. And when it comes to the crunch, it is Nathan himself who succeeds in preventing the disaster that threatens to destroy their lives.

Valerie Mendes’ gripping, fast-moving novel explores the strengths of friendship, and the inescapable, binding pull of teenage love.

One

Nathan didn’t see it coming.

On that last day of the summer holidays he sat at Tom’s desk, his sketchbook on his knees, as if it were an ordinary morning. Tom, wedged into his beanbag, engrossed in

Lord of the Flies,

was today a still and willing subject.

Nathan’s hair stood up in spiky black strands as his charcoal lovingly skimmed and scraped the paper’s surface. And snapped.

Nathan cursed. “That’s messed up your chin. And it’s my last piece.”

“You shouldn’t press so heavily.” Tom read on.

“I don’t. It’s artistic fervour. … It’s almost finished anyway.” Nathan stood up, stretched his back and arms. “Let’s go for a swim. While we still have our freedom.”

“You’d better fetch your things, then.” Tom glanced at him. “And get some more charcoal from your desk while you’re about it. You never finish anything properly.”

“Yes, I do.”

“No, you don’t. You check that book of sketches and tell me how many need more work.”

Nathan threw a pillow at Tom’s head and clattered down the stairs. He and Tom lived on opposite sides of the same south London square. They’d met when they were six and had been best friends now for more than seven years. As they grew, they looked less alike: Nathan tall, gangling, dark-haired; Tom neat, small-boned, freckled. Nathan scatterbrained but sometimes brilliant; Tom methodical, thorough, organised as an army of ants.

Nathan Fielding and Tom Banks. Weed and Banksie. Closer than two fingers on a hand.

Now Nathan began to run across the square. Then he stopped. His trainers squealed like mice. The front door of his house gaped open. Bags littered the steps and Dad’s Ford stood outside. But he’d left for work that morning. Why was he home? Perhaps he had to go on a business trip? He hadn’t said anything, which was odd.

Dad came to the door, his grey hair falling over his forehead. Then Mum burst out on to the step. She tried to stroke Dad’s shoulders, as if she were pleading with him. But Dad shrugged her off and picked up the bags.

Cold slivers stabbed at Nathan’s throat. “Dad!”

Dad hadn’t heard him. He ran down the steps and flung the bags into the boot. He climbed into the car, revved the engine and swung out of the square. Mum stared after him. Then she turned and slammed the door.

Nathan raced into the house and made for the kitchen. Mum had lit a cigarette. Her face shone with sweat and her straight dark fringe lay damp on her forehead.

“I’ve just seen Dad leaving.” Nathan’s mouth tasted sour. “What’s going on?”

So Mum told him. That Dad had left them to live with a girl called Karen. She was a designer on Dad’s new music magazine. Karen was divorced. Karen had a three-year-old daughter. She lived near Primrose Hill. Dad had been in love with her for ages.

Disbelief buzzed in Nathan’s head like a trapped wasp.

“It’s absurd.” Mum crushed out the cigarette. “I spend my life as the nation’s agony aunt. Tell me your problems and ‘Dear Lizzie’ can help. But when it happens to me, all I want to do is curl up in a dark room and cry.”

Blood rushed to Nathan’s face.

Dad with another woman.

“I don’t believe it.”

“It’s the truth, so you’ll have to.” She reached across the table to grip his hand. “I know it’s a shock, but you’ll see him lots. That’s what he wants.” Her fingers tightened. “He loves you very much.”

“What a great way to show it.” Nathan wrenched his hand away. “He’s dumped me like I don’t even exist.”

“I’m not defending him.” Mum looked suddenly older, crumpled. “But I don’t want you to take

against

him. … He’s coming to lunch on Sunday.”

“But this is Monday. School starts tomorrow. I can’t start a new term without Dad.”

“You’ll have to. He needs time to settle in with Karen.”

“So where’s his time for

me

? He’ll always be somewhere else, on the end of a stupid phone.”

“I’ll leave you alone to talk on Sunday. I won’t get in the way of you and Dad. I promise. I’ll make sure you stay in touch.”

“This morning,” Nathan said, remembering how he and Dad had made breakfast together. “You must’ve been pretending like mad.”

“I wasn’t pretending. I hoped he’d change his mind. Just now – I prayed he wouldn’t drive away. … Do you think I

wanted

this to happen?” She stood up and held out her arms. “Come and give me a hug.”

Nathan glared at her.

I don’t want you. I want Dad.

He threw back his chair, ran from the kitchen up to his room, slammed the door. He stared at the crumpled duvet, the untidy desk, the scattered books and comics. His head throbbed.

Mum tapped on the door. “Nathan? Are you OK?”

“Yes.”

I must not cry.

“I’m late for a meeting.”

“Don’t worry about me. I’m going back to Tom’s.”

“See you tonight, then. I’ll make us something special.”

“Whatever.”

Leave me alone.

He leaned against the door, listening. Feet ran down the stairs and the front door slammed. He went to the window. She looked back at him, but neither of them waved. Then she walked on.

For a moment Nathan wanted to run after her, to tell her everything would be OK. But the anger returned, squashing the pity. He ran downstairs and out to the steps. The air stank of fumes. Another car was parked where Dad’s had been.

Needle tears pricked his eyes. He walked, the square a blur.

Tom stood by his front door. “So where’s your swimming gear?”

Nathan stared at him. “What?”

“Wake up, Weed. You look as if—” Tom’s eyes narrowed. He moved down the path towards Nathan. “Something’s happened.”

“You could say that.” Nathan gripped Tom’s gate. “It’s my dad.”