The Drinking Den (2 page)

Authors: Emile Zola

(New readers are advised that this Introduction

makes the details of the plot explicit.)

The Drinking Den (L'Assommoir)

1

was one of the publishing sensations of nineteenth-century French literature, selling out edition after edition from the time of its first publication in January 1877; by November of that year it had already reached sales of fifty thousand copies. The success represented a turning-point in Emile Zola's life, confirming his reputation as one of the leading figures in the literary world of his time and the most prominent exponent of literary Naturalism. It also brought him a measure of financial stability and allowed him to buy a house, in Médan.

He was coming up to his thirty-seventh birthday â it fell on 2 April 1877 â and was already the author of a collection of short stories, three plays and eleven other novels, as well as a steady output of journalism. He contributed regularly to the Russian review

Vestnik Evropy

, published in St Petersburg by Mikhail Stassiulevich, who had been introduced to Zola by their friend, the writer Ivan Turgeniev. Zola's novels were rapidly translated into Russian and his reputation, at least before the publication of

L'Assommoir

, was probably higher in St Petersburg than it was in Paris.

However, the success of

The Drinking Den

was to a great extent a

succès de scandale

. Before its appearance in book form, the novel had been published in instalments in

Le Bien public

, from April 1876, and immediately attracted hostile criticism. After six parts, publication was suspended, and not resumed until later in the year in a different newspaper,

La République des lettres

(from July 1876 to January 1877), concluding a couple of weeks before the book itself came out, on 24 January. By that time, Zola's novel was already notorious and the subject of heated debate. Subscribers to

Le Bien public

had threatened

to cancel their subscriptions if the paper continued to carry

The Drinking Den

. A writer in

Le Figaro

described it as ânot realism, but filth; not crudity, but pornography'. It was denounced by

Le Gaulois

as âan inexcusable scandal'. Even some of Zola's friends had reservations. Guy de Maupassant and Stéphane Mallarmé were enthusiastic, and Joris-Karl Huysmans wrote an appreciative review; but Turgeniev told Ludwig Pietsch that he had read the book âwith a mixture of horror and admiration'. Gustave Flaubert, with whom Zola was engaged in a continuing debate on literary realism, found it shocking because of the use of popular speech and the depiction of poverty and working-class life, while the Goncourt brothers felt that

The Drinking Den

owed an unacknowledged debt to their own fiction, for example, the novel

Germinie Lacerteux

(1864), which dealt with the life of an impoverished and dissolute servant girl. The charge of plagiarism was renewed with respect to other works, especially Denis Poulot's study of Parisian popular culture,

Le Sublime

(1870) â which Zola freely admitted having used as one of his sources for information about working-class speech and manners.

There were two immediate effects of the scandal. Not only did it ensure fame and fortune for the author, it also induced him to make a number of very specific statements about his intentions in writing

The Drinking Den

, in order to correct what he saw as his critics' mistakes in their reading of the book. These statements appeared in letters to the newspapers and in the Preface to the novel (which is translated below); Zola was to develop his literary theories in

Les Soirées de Médan

and

Le Roman expérimental

, both of which were published in 1880. As a result, we know a good deal about what he hoped to achieve with

The Drinking Den

. An author may not always be the best judge of his own work, but his point of view must be of special interest. Since he was answering what were mainly moral strictures, he emphasizes the moral lessons of the novel, the significance of the characters and their behaviour, and the relation of the events to the social realities of his time. He was also attacked, in particular, for his use of vulgar language and he defends this, countering with a charge of hypocrisy against those who would prefer him to have written in a more elevated manner: âAll the anger directed against the stylistic experiment that I have attempted, is too hypocritical for me to answer itâ¦'

2

Zola's defence is concerned first of all with those aspects of the novel that have been the subject of hostile criticism; it leaves aside questions of aesthetics, for example, in a novel that had been thought out and constructed with great care. More than its moral impact or its alleged indecency,

The Drinking Den

interested critics in the second half of the twentieth century because of its rigorous structure, and its symbolic or mythical dimensions, some of which Zola certainly intended us to find. There is always a lot more to Zola than appears. From the Goncourt brothers onwards, commentators on him have observed how difficult he was to pin down, both in his work and in his personality; he is a site of continual contradictions. Taking simply the question of the moral intentions of his work, one can see him in this novel preaching the most conventional bourgeois morality even as he works to challenge its assumptions, condemning Nana for her âvicious nature' while patently sympathizing with her circumstances and her distaste for conventional hypocrisies, depicting Gervaise as at once a victim of her environment and of her own weaknesses, and so on. Throughout his life and work, Zola was torn between idealism and despair, a need to show the worst of life as he saw it and a need to express the human yearning for something higher and better. Zola the atheist coexists with Zola the religious enthusiast, Zola the scientist with Zola the artist.

In the year after the scandal of

The Drinking Den

, Zola deliberately set about writing a novel that would contrast with it.

Une page d'amour

(1878) is the story of a middle-class woman who falls in love with a doctor after he has saved the life of her child, but eventually renounces him for reasons of convention and morality â âan interlude of tenderness and sweetness', Zola called it; though he had doubts whether his readers would approve. They were not disappointed, however, in his next work,

Nana

(1880), which takes up the story of Anna Coupeau, the young woman whom they had already met in

The Drinking Den

and who, as was already clear from this novel, was destined for a life of high-class prostitution. The outcry from the bourgeois press at this glimpse of the underside of French society was even greater than it had been at the time of

The Drinking Den

, and the new novel sold more rapidly than its scandalous predecessor.

*

The Drinking Den, Une page d'amour

and

Nana

were the seventh, eighth and the ninth in the cycle of novels called the Rougon-Macquart and subtitled âThe Natural and Social History of a Family under the Second Empire'. Zola had planned this panoramic survey of French society and started to write the first volume before the Franco-Prussian war, which, in 1870, marked the end of Napoleon III's reign and the imperial regime. The whole cycle would eventually reach twenty volumes, ending in 1893 with

Le Docteur Pascal

.

The aim of the Rougon-Macquart novels was to put into practice the concepts of Naturalism, the literary doctrine that Zola had started to elaborate as early as the 1860s. The Naturalist writer saw himself, in opposition particularly to the exponents of Romanticism, as comparable to a scientist or ânatural philosopher', observing the interaction between society and individuals, and describing the results of these observations in novels that would expound them with scientific rigour. Naturalism was therefore a development of Realism, which made use of scientific discoveries, including theories of heredity: the Rougon-Macquart as a whole was designed to illustrate the transmission of hereditary traits from one generation to the next in the families of the Rougons and the Macquarts, and the influence on individuals of this heredity, in conjunction with the social environment in which they happened to live: it was thus, in theory, to become in itself the working out of a complex âscientific' experiment. Both families have a common ancestor, Adélaïde Fouque, whose son, Pierre Rougon, founds the respectable, legitimate, bourgeois branch, while her two illegitimate children, Antoine and Ursule, give rise to the working-class Macquarts. The whole cycle covers a wide spectrum of social classes and milieux, from the peasantry and the industrial working class, to the financial bourgeoisie, the priesthood, artistic circles, politics and the army; and from the countryside and provincial towns to the market district of Paris, a department store, a coal mine, theatres and cabarets, and the Stock Exchange.

Time has disproved some of the scientific ideas on which Zola based the overall design of the work â though, when it came down to it, these notions proved to be less prominent in the design than he had originally expected them to be. But, while time may have detracted from the

value of the Rougon-Macquart series as a scientific experiment, it has compensated by greatly enhancing its interest as an imaginative evocation of a particular period in nineteenth-century French history, based on personal observation and sociological research. Zola started to plan

The Drinking Den

in detail as early as 1875. In the autumn of that year, he returned to Paris from his summer holiday in Normandy and at once set about walking the streets and visiting working people, in order to gather material for the novel.

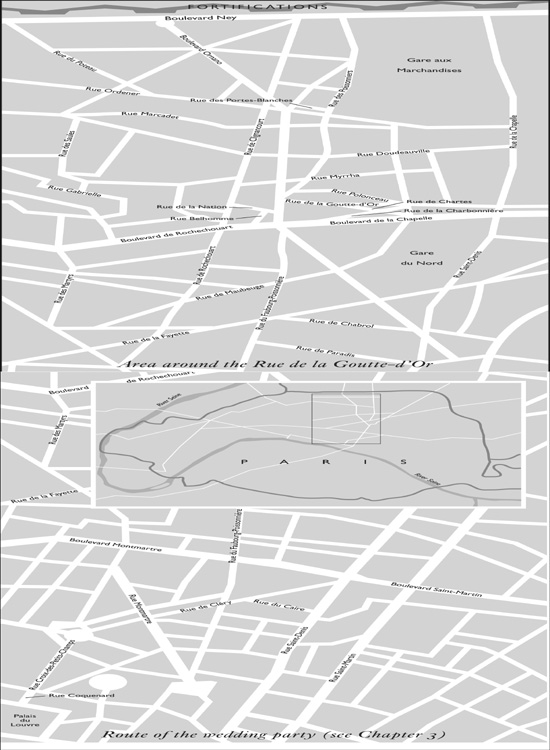

Every street through which the characters pass is named; the events of the story can be followed precisely on a contemporary map of Paris. Details of prices and wages, living conditions and language, working practices, drinking habits and

delirium tremens

are taken from observation or the best available sources. Zola's notebooks survive and show how meticulously he recorded details concerning localities and trades (for example, how laundresses were paid and the different kinds of flat-iron or other tools that they used). The action of the novel is situated, year by year, with occasional references to contemporary events such as the assumption of power by Louis Bonaparte, the building of the Lariboisière Hospital or the huge urbanization programme of Baron Haussmann. Not that this is any dry sociological record; on the contrary, central to Zola's Naturalistic literary method was the use of language to convey the sights, smells and sounds of the novel's locations with the greatest possible precision. Few writers convey so vivid and immediate a sense of what it felt like to live in a particular place, at a particular moment in history.

The historical moment is vital. The Second Empire was to be a discrete interlude in French history, twenty years of imperial rule sandwiched between two republics; and even at the time, without the benefit of hindsight, it often appeared arbitrary or inconsequential â the very opposite of rational government for a positive and scientific age.

3

Its leader, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon I, was a slightly eccentric, rootless, even bohemian figure. He had spent many years as an exile in England, becoming the hereditary leader of the Bonapartists after the death of Napoleon's son in 1832. Returning to Paris after the Revolution of 1848, he was elected a deputy to the National Assembly under the Second Republic, then its President. In

December 1851, he carried out

a putsch

to make himself head of state without any constitutional constraints and proclaimed himself Emperor a year later, in December 1852.

An aura of dissolution and corruption hovered around Louis Bonaparte's government. Republicans, naturally, hated and despised it for its illegitimacy and arbitrary exercise of power. It was characterized, too, by its ostentation and pretensions to grandeur. Abroad, the years of the Second Empire were marked by colonial expansion (in Africa, Indochina and the Pacific) and by the war in the Crimea. At home, France was at the height of an industrial revolution. Typical of the regime's grandiose posturing, as well as its energy, were the public works carried out in Paris under Haussmann, which involved massive slum clearance and the creation of the wide boulevards that give modern Paris much of its personality. Perhaps designed to encourage gentrification of areas that might otherwise have remained solidly working class â and having the effect of making access to such areas easier for the Army and the police, in the event of popular uprisings â these âimprovements' also made the city more hygienic and pleasant to live in. They are specifically referred to in

The Drinking Den

(especially in Chapter 11).

The Empire ended after the French defeat by the Prussians at Sedan in September 1870, when Napoleon III abdicated. The following year saw the attempt to install a radical Socialist regime under the Paris Commune, which was harshly repressed by the government of Adolphe Thiers. Zola, who had spent part of the period of the Commune in Paris, continued to work hard on

La Curée

, the second novel in the cycle of the Rougon-Macquart; the first,

La Fortune des Rougon

, was about to appear as the Commune fell.