The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini and other Strange Stories (24 page)

Read The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini and other Strange Stories Online

Authors: Reggie Oliver

I felt a mixture of emotions, but the principal one was of dismay. I wished I had never seen the will. I decided not to tell my mother, knowing that she would have gone into battle over it on my behalf, and that was not what I wanted. I did feel, however, that Uncle Alfred owed me some answers, so I rang him up at Glebe Place. The telephone was answered in the curtest way possible by his housekeeper Mrs Piercey. Mr Alfred Vilier was seeing nobody; he was ill; he knew nothing about a nephew; goodbye. A few weeks later he died, though I was not informed of this and consequently did not attend the funeral.

About a year after his death I happened to meet one of Alfred’s last remaining friends, a dealer in theatrical memorabilia. He told me terrible things about Alfred’s last days: how he had become increasingly reclusive, refused to go out, and had come to hate any kind of natural light or scenery. All the curtains in the house were permanently drawn. The dealer told me that in the end he could not bear to go there, the oppression was so tangible, the ever-present Mrs Piercey so unwelcoming. Alfred retreated to his bedroom and was found one morning by Mrs Piercey to have suffocated himself by tying a plastic bag around his head. A bizarre detail given to me by the dealer sticks in my mind: it was a Harrods plastic bag, apparently, of the customary dull green with the word ‘Harrods’ and the Royal Warrant emblazoned in gold upon it.

I half expected that out of guilt Uncle Alfred might make me heir to his estate, but I was disappointed. The bulk of his fortune and the house in Glebe Place was left to Mrs Piercey. The theatrical memorabilia was left to a museum and I was made the inheritor of one black japanned tin trunk labelled ‘Family Papers’. The label did not lie: the trunk was full of family papers of the dullest kind. Only one item was of any interest. It was a smallish mahogany box, with brass corners and decorated with a simple brass inlay, at a guess early nineteenth-century.

In the box which was lined with dark green velvet were two oval miniatures in gold frames. Their quality and the date 1814 engraved on their backs, suggested the work of Richard Cosway or one of his many talented pupils. They were head and shoulders portraits of a man and woman, young, handsome and dressed in the height of fashion. The woman had dark brown hair and delicate features, but there was something not quite likeable about the simpering expression which just showed her teeth: a certain capriciousness was suggested. You had the feeling that this was someone who might do or say anything on a whim, and be totally unaware of the damage she had caused. The picture of the man was much more striking. It was a brooding, Byronic face, not unlike the portraits one sees of the young Beethoven. A curious feature of the miniature was that he seemed to be looking intently at something slightly below his eye level and to his left. What that look meant precisely was unfathomable, but it was not at all pleasant. There were no names engraved on the miniatures and nothing to suggest who their subjects were, except for the only other thing in the box. It was a frail, yellowing copy of a journal called

The

Monthly Intellegencer

dated December 1819. The

Intellegencer

was a tabloid-sized scandal sheet, typical of the period, whose longest items consisted of no more than two or three paragraphs. A heavy line in pencil was drawn down beside a paragraph which was headed:

HORRIFIC EVENTS AT THE

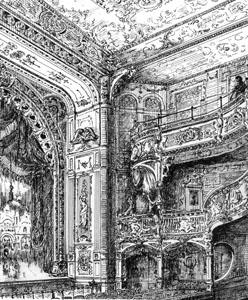

ROYAL COBURG THEATRE.

It read as follows:

On the 10th of this past month of November, during a performance of

Elvira; or the Martyred Bride

at the Royal Coburg Theatre, a startling and most lamentable series of incidents was observed to be taking place in one of the stage boxes. Sir George and Lady Vilier, a couple noted for moving in the most fashionable and elevated circles, having taken the box, appeared to be engaged in a fierce altercation during the performance. Suddenly Sir George was seen to seize his wife Lady Hester by the throat and begin to choke the life out of her. Before effective assistance could be rendered to the unfortunate lady she had expired under her husband’s violent assault. Sir George was immediately apprehended and is to stand trial shortly. It is widely believed that Sir George Vilier was possessed by an epileptic seizure in the course of which the balance of his mind was deranged. No other explanation can be found to account for the conduct of a gentleman widely regarded as a model of genteel manners and an ornament to his station in life. It has been said, we know not with what authority, that Sir George had of late lost large sums at cards and that he attributed his ill fortune to the colour green which he ever considered a most unlucky colour, and that on the night of the tragedy Lady Hester had on a new gown of bright green taffeta.

**

At last the wickedness was unwinding and, one evening, as I was doing the

Times

crossword, I recognised the anagrammatic significance of Valerie Fridl and the final thread was unravelled.

THE GOLDEN BASILICA

‘You were at Oxford?’

‘Yes.’

‘Ah. My son was at Oxford. Before your time. Christ Church. The House, you know.’

‘Yes.’

‘Were you at The House?’

‘No. Oriel.’

‘Ah, my son was up at The House, as they say. He lives in Italy. Professor at Venice University. He’s written a book, you know.’

‘What kind of book?’

‘It’s a masterpiece. It’s called

The Golden Basilica.

I’m going to have it made into a play. Yes.’

This odd fragment of conversation occurred in equally unlikely surroundings. The man with the son who had been at Christ Church was sitting opposite me in a large bare room at the YMCA in Great Russell Street. He was supposedly interviewing me for a Summer repertory season at the Royalty Theatre, Seaburgh and his name was John Digby Phelps. He was a pale, flabby man in his sixties, with the greasy remnants of curly blonde hair clinging to his large cranium. His eyes were grey, protuberant and watery. He brought to mind one of those creatures that fishermen haul up from the dark depths of the sea, accustomed to silent, murky regions of the biosphere, an impression enhanced by a baggy grey suit, shiny with age. Conversation streamed from him in a bubbling monotone, full of dropped names, and mild but insistent self-aggrandisement.

I had gone to see Phelps, the director and owner of the Royalty Theatre, to read for a number of leading roles in his season, but he was more interested in talking about himself than auditioning me. He seemed impressed by the fact that I had been to Oxford and that I talked, as he put it, ‘like a gentleman’. This rather relieved me because I felt at the time that these two factors often weighed against me with other more democratically inclined directors. Mr Phelps’s snobbery was, objectively speaking, repulsive, but, as far as I was concerned, it was redressing a balance. I read one or two speeches out of various plays, but I could tell he was hardly listening to me. He had made up his mind. A few days later a letter arrived from him offering me a three-month season at Seaburgh. My misgivings about Phelps himself only slightly dampened my pleasure and relief: almost a quarter of the year would be spent in gainful employment.

But the strange conversation about

The Golden Basilica

stayed in my mind and before I went up to Seaburgh I spent a fruitless afternoon looking for a book with such a title in libraries and bookshops. The title appealed to me: I had a vague idea of

The Golden Basilica

being an elegant, witty novel about English expatriates in Italy with perhaps a touch of E.M. Forster or even Henry James about it. I have no idea why I thought that. Out-of-work actors are prone to such ruminative fantasies: they will watch the mannerisms of someone sitting opposite them in the tube and construct whole dramas out of a few simple observations. Actually, I was almost relieved not to find a copy of

The Golden Basilica.

It meant that my fantasy could soar, ungrounded by reality.

About the Seaburgh season itself there is little to say. The company was good and the plays decent. We performed a repertoire of four plays consisting of

Deathtrap

,

Gaslight

and a couple of Alan Ayckbourn comedies. All of them, especially the Ayckbourns, went down well with Seaburgh audiences and were enjoyable to perform. Once the plays were rehearsed and in the repertoire we had a good deal of leisure.

However, there were peculiarities about the way the season was run which made the company uneasy at times. These peculiarities all emanated from John Digby Phelps. Though billed as director of the plays, he did not direct. He would scrawl a few pencilled notes on the printed edition of the plays, underline all the stage directions and then instruct the company stage manager to take rehearsals. The results gained by this method were indistinguishable from those achieved by the average theatre director, but it was evidence of his strange personality. Very occasionally Phelps was seen prowling round the back of the auditorium during a performance, but he rarely stayed for the entire duration of the play. The day after these visits he would deliver notes on the performance via the stage manager and they would be on two subjects only. The first was our appearance. If he took a dislike to an actor or actress’s hairstyle or dress, he could be severe, sometimes demanding a dress parade before the show to make sure that the desired adjustments had been made. The other theme of his comments was the curtain speech which thanked the audience and announced the forthcoming attraction. The exact words of the curtain speeches for every play were typed and pinned to a notice board, the slightest deviation from them bringing down sharp reproof, even threats of dismissal. Phelps’s conduct was sometimes described as eccentric, but eccentric is a subjective term. An analysis of his behaviour showed a pattern consistent with egocentricity rather than eccentricity.

For some reason, perhaps because of the Oxford connection, Phelps took a liking to me. I did not welcome this favour because it made the other members of the company suspicious that I was somehow ‘on his side’. In order to disabuse them I had regularly to make uncomplimentary remarks about him. This was not always safe to do, especially in the theatre, as Mrs Phelps was usually about.

Joy Phelps was Phelps’s second wife, a mousy, furtive little woman, twenty years his junior. She ran the box office and the bar. She cleaned and managed the theatre almost single-handedly, sometimes assisted by her elderly mother, a presence even more shadowy and unforthcoming than her inappropriately named daughter. If any repair work was needed on the theatre, Joy’s brother, a shrivelled imp called Ron, would turn up in a van that may once have been white. Their presence added to the stuffy, inward-looking atmosphere of the place.

One morning, as I was about to go into rehearsals, I was waylaid by Joy in the theatre foyer. I often came in through the front of house rather than by the stage door because our mail was delivered to the box office. She summoned me so secretively into her sanctum that I began to be afraid that something terrible had happened. Had a phone call come through announcing that my parents had died in an air crash? A hundred ugly possibilities rushed through my mind before she relieved my anxiety. Would I, she asked me almost in a whisper, if I were free, come and have tea with Mr Phelps at about four on Sunday? When I had said yes, she gave me directions to his house which was a short bus ride out of Seaburgh. I would be expected at four. She relayed these instructions in a solemn, urgent tone as if afraid that I would disobey or, worse, misunderstand them. She also intimated, in a roundabout way, that I was not to tell the others in the company about my visit. The implication was that Phelps’s invitation was an enormous privilege of which they might be jealous. I had no intention of telling my fellow actors but for the slightly different reason that it would confirm their suspicion that I was Mr Phelps’s toady.

Phelps lived in a village called Tiddenham about three miles out of Seaburgh in smooth, unspectacular East Anglian countryside. His house, the Old Rectory, stood by the church in its own grounds, a large grey, early nineteenth-century building on two floors with a severe Doric porch. Buildings provoke an instant reaction from me in a way that people don’t, and I disliked the Old Rectory at once. Perhaps it was the day on which I first came to it, humid and threatening rain; perhaps it was the dreary garden which surrounded it, all gravel paths, lawns and laurel bushes; perhaps it was the pretentious austerity of its architecture; or perhaps it was the dread of meeting its occupants socially for the first time. Whatever the cause I was attacked by an almost overwhelming sense of oppression as I was about to ring the front door bell. It was exactly four o’clock.

I must have waited three minutes before I heard shuffling footsteps and the door was opened about half an inch by a hideous old woman in a blue overall with a bright red gash of lipstick around her mouth. I explained who I was.

‘You should have come in round the back,’ she said brusquely. I started to walk away. In a slightly more conciliatory tone she added: ‘You’d better come in.’

I entered a large unlit hallway whose walls were hung with big, uncleaned pictures of dubious quality. To my left a door opened and Phelps emerged palely into the gloom. He wore cavalry twill trousers and a patched sports jacket of yellowish check. In these surroundings he more than ever resembled some dim submarine creature.

‘Ah! There you are,’ he said. ‘Did no-one tell you to come in round the back?’

‘No,’ I said, wondering guiltily whether Mrs Phelps would suffer for this omission in her instructions.

‘

I

told him to go round the back,’ said the old woman.

‘Ah,’ said Phelps. ‘Get the tea then, Nanny.’ Nanny shuffled off to get the tea, but not before giving me a venomous look.

Phelps summoned me into the drawing room, which was well-proportioned and furnished in the approved country house style with a chintz three piece suite and a few good items of eighteenth-century furniture. Coloured George Morland prints adorned the walls. It was all correct and elegant; the silver on display was Georgian and well-polished, but there was no character. Nothing there had been chosen with love or enthusiasm. It looked like a stage set furnished to create the right impression of gentility:

The drawing room of the Old Rectory, Tiddenham, one dull afternoon in July

. Over the mantelpiece was an undistinguished early nineteenth-century landscape in oils.

‘You see that?’ said Phelps. I nodded. ‘A Constable. You know how to tell a Constable? He always hides a face in his landscapes. You see. There!’ He pointed to a part of the painting. There was indeed a sort of face to be discerned in the configuration of the rocks beside a small stream in which a lumpy, misshapen boy was dully fishing. I had never heard of Constable putting a face in his landscapes, and this was no Constable, but I stayed silent. I had neither the courage to contradict him, nor the cravenness to agree.

Nanny came in with tea and cake on a silver tray, laying it down on a low table in front of the fireplace.

‘This is Nanny,’ said Phelps gesturing towards her as if exhibiting a prize pig. ‘Not my nanny, but my son’s. Stayed on after he’d gone. Stayed on to serve me. Loyalty, you see. Yes.’ Nanny left the room without indicating by so much as the flicker of an eyelid that she had heard this tribute.

Seeing only two teacups on the tray, I asked if Mrs Phelps would be joining us.

‘No, no,’ said Phelps who seemed disconcerted by the question. ‘She’s busy, you know. Visiting her mother . . . or something. She wouldn’t understand what we were talking about. She’s not a theatre professional like us. Help yourself to tea. And have some of that sponge cake. Made by Nanny. Superb. She wins prizes for it, you know.’ The cake was good, but had a suspiciously pristine, shop-bought look about it.

Our conversation during the next two hours consisted largely of a monologue about the theatre from Phelps punctuated by nods and murmurs from me when he seemed to require them. I tried to make these as ambiguous and unacquiescent as courtesy would allow since his views were fairly absurd. Occasionally he would ask me questions about the season and other members of the company. He seemed particularly interested in any rivalry or tension there might be among us, and he asked me my opinion, ‘in strictest confidence, of course’, of their acting abilities. I made my answers bland, sensing that he would not hesitate to exploit any indiscretion.

One topic recurred again and again in his monologues and this was

The Golden Basilica

, the work written by his son. He had the most grandiose plans for it. It was to be made into a play and performed in his theatre. Then it would be filmed, mostly in his theatre as well, though with a few external shots using the ‘magnificent East Anglian scenery’. He made it sound as if this too, like the theatre, was his property. I was intrigued, but every time I tried to find out what was

The Golden Basilica

and what was its story or theme, he became vague or replied simply that it was ‘a masterpiece’. Frustrated, I said, teasingly, that

The Golden Basilica

was certainly a splendid title. Phelps showed no awareness of the veiled irony, but seemed immensely gratified by what I had said. He picked up a silver framed photograph from a side table.

‘There you are,’ he said. ‘My son, Peter Digby Phelps. M.A. Oxon. Like you.’

The photograph, at a guess fifteen or twenty years old, showed the head and shoulders of a young man in his twenties. One could see the resemblance to his father in the slightly blunt features and the crinkly blond hair, but he was better looking than Phelps could ever have been. The father must have looked on his son as an idealised version of himself. A touch too of Phelps’s pretension was to be found in the ostentatiously large spotted cravat he wore. The expression was vaguely self-important, but gave little away.

‘Done while he was up at The House. He was a very popular figure. Joined all the clubs, you know. The Grid, the Bullingdon. Spoke at the Union. Great success. Double first in Economics and so on.’