The Dream Widow (2 page)

Authors: Stephen Colegrove

Tags: #Hard Science Fiction, #High Tech, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Post-Apocalyptic, #Adventure, #Literature & Fiction

Perspective shifts three hundred years in the past to 2053. JACK GARCIA is a survival expert working at the military complex high in the mountains that becomes Wilson’s home. The facility researches astronaut survival on alien planets and hibernation technology for space travel. A deadly virus spreads across the nation. With nuclear war imminent, Jack is sent down the mountain to retrieve a special device from a base in the east––the same device Wilson seeks for Badger’s cure. Jack finds the device but is badly injured during a nuclear strike on the city.

An ugly dog drags Wilson from his grave, and his implant wakes him after five days in a coma. He rescues Badger and they struggle through the mountains to David. The Circle follow and destroy the village with advanced weaponry and a tank.

Wilson leads the survivors west to Station and takes Badger to the underground tombs where the old technology is implanted. A mysterious voice cures Badger and reveals himself to be a 350-year-old Jack Garcia. He was badly injured during the nuclear strike on Colorado Springs but his friends returned him and the sequencer to the mountain base. The only option for his survival was to place him in hibernation. Many of the base leadership also entered chambers, but over time all died or left for the outside world. Jack and two ‘vegetables’ are the only survivors.

With Badger cured and most of their questions answered, Wilson and Badger leave the underground tombs.

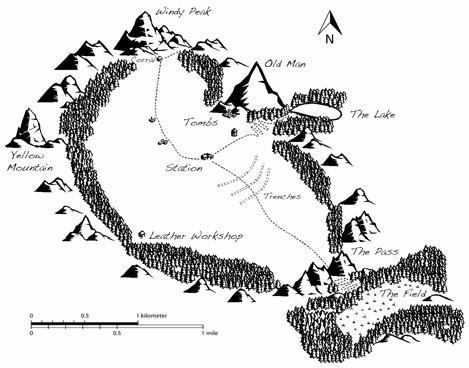

Map of Station and the Valley

The following map, although not exactly to scale, indicates the major features of Station including: Old Man, The Tombs, Windy Peak, Yellow Mountain, The Corral, Leather Workshop, Trenches, Pass, Lake, and the Field.

ONE

B

lood pressure’s dropping––I can’t believe you sent him through decon.

Why not?

Just look at him!

Stop talking and get another line. Use the jugular.

Got it.

As long as there’s power we save his life, end of the world or not.

The man startled at the sound of a book dropped on marble. He tried to speak but his teeth clicked on hard plastic in his mouth.

Watch out, he’s waking up. Give him twenty more.

That’s too much.

Do it.

The man woke underwater covered in azure light and a web of black cables. He thrashed in the liquid until he realized he was not drowning. Somehow, impossibly, he breathed. After a day, a month, or a handful of seconds the visions began.

An English garden hedged in cedar. A red-fruited hawthorn. A cinnamon tree.

The man’s left hand rested on the snow-white armrest of a wooden recliner. He stared at it, touched it with his fingers.

“How does it feel?”

A doctor with a beard like slapped-on coffee grounds sat in a chair across from the man.

“Is this Heaven or Hell?” asked the man.

The doctor smiled. “Neither, because you’re not dead. You survived.”

“Survived what?”

“You were badly injured after the nuclear blast. Do you remember the crash?”

The man shook his head.

“We had to amputate your legs above the knee and your right arm. To save your life we had to put you in one of the controller beds.”

The man stared at the sandals on his feet and his tan cargo shorts. He wiggled his toes.

“Those aren’t real,” said the doctor. “And neither am I. This is ... think of it as a space in your mind. You control parts of it.”

“This is what we worked on at Altmann, isn’t it?”

The doctor nodded. “Don’t worry––I’ll be here to help you deal with everything. I owe you that much.”

The man stared at the fingernails on his left hand. All were cut short. The index and middle fingernails were black with grime.

“Greg?”

The doctor was gone.

Over time he spoke with the others who floated in separate tanks nearby or lay in caskets along the walls. He began to see outside the garden. He watched the survivors in the valley plow the earth, hunt mule deer, and relearn what had been forgotten.

The others in their tanks of jumbled wire taught the man how to control the systems in the bunkers. The garden was the keystone, a mask for levers in his mind. He learned everything from the absorption rate of control rods in the power plant to the maximum pressure load on a personal shower head. More importantly, he learned how to keep the survivors warm and safe.

The man slept for months, sometimes years at a time, until woken by a chirping alarm or timed maintenance request. The people he’d known before the war grew old and died in the bunkers. Sometimes he wished the surgeons had failed, that his saviors had left him in the twisted wreckage of the minivan. When his wife passed away at the age of seventy-two he refused to speak for half a century.

WILSON AIMED HIS CROSSBOW at the mule deer but the tiny, white-painted sights twirled like fireflies. He shot his bolt and missed. Before the brown-eyed doe could flee into the night, bolts from the two other boys thumped into her chest. The doe thrashed in the leaves for only a moment.

The two boys untied Wilson from the tree-stand and built a campfire. All three relaxed, enjoying the smell of roasted venison and the warmth of crackling flames. Wilson’s face and lips were still numb from the blackberry wine.

“This is a stupid tradition,” he said.

“Stupid or not, you’d feel bad if you didn’t do it,” said Mast, the bigger of the three.

“Hey, Wilson,” said the other one, a thin boy. “What do you and a goat have in common?”

“I don’t know, Robb.”

“You’ll both be tied up tomorrow!”

Robb fell backwards and rolled on the leaves in a fit of giggles.

“Thanks for the fortieth joke about that,” said Wilson.

“Just ignore him and cheer up, friend,” said Mast.

Wilson stared at the fire and listened to drips of deer fat pop on the logs. “What was in that wine you gave me?”

Mast shrugged. “Nothing but the special ingredient.”

“You’re both lucky I didn’t shoot you.”

“We’re all lucky. In the old days you had to kill a bear before the wedding.”

“I think–”

“You’re going to be sick?”

“Yes, and I think a doe is more appro.... pp...priate....”

“Don’t throw up near me! Get away,” said Robb.

Mast shook his head. “To think that Badger has to look at your ugly face for the rest of her life. It’s making me sick, too.”

Wilson wiped his mouth. “What a great friend.”

“I know. You’re welcome.”

Robb had stopped giggling. He’d taken off his moccasins and now cleaned his toes with a stick.

“Tell us about the Circle machines, Wilson.”

“For the love of cats, stop asking him,” said Mast.

“But I want to hear how he blew up the tank.”

Wilson shook his head. “All I saw was a fireball. Stop asking me about it.”

“No need to get mad,” said Mast. “It’s your special night. Aren’t you having fun?”

“I’m sorry. It’s just ... things are changing too fast,” said Wilson. “After my father’s death, the escape, and the attack on the village, I don’t want to talk about the Circle. I feel like Darius could show up at any moment.”

“That guy? He’s got to be dead. You said Badger cut off his–”

“Don’t say it.”

“Fine,” said Mast. “But I’d be more worried about that fossilized graybeard under the mountain. With all those machines keeping him alive, he’s barely human. What if he snaps over breakfast and floods the valley with gas?”

“If he even eats breakfast,” said Robb.

“Listen, I know Jack better than anyone,” said Wilson. “He’s kept us safe for three hundred years, he’s not going to chuck everything in the bin because it’s a Tuesday.”

Robb looked up from his toe-cleaning. “Today’s Saturday!”

“That was an example.”

Mast pointed at Robb. “Like you: an example of how to shave a bobcat and teach it to walk.”

Robb hissed.

BADGER ADDED A CUP of water to the mixture of cornmeal, lard, salt, and honey and stirred the dough. She’d only been doing this for an hour but her hands were aching.

“This is a stupid tradition,” she said.

“Aren’t they all, dear?” said Wilson’s mother, Mary, from the other end of the kitchen. She twisted a dial that controlled temperature for the wall oven.

“Yes, but this one is even stupider. I should be the one hunting a deer and he should be making the bread.”

“It’s only for tonight. After the wedding you two can ‘bake bread’ however you want.”

“What do you mean?”

Mary ignored the question and peered into the bowl of cornmeal dough. “Needs more water.”

Badger wrinkled her nose and mixed another bowl.

“I just don’t understand why you like hunting and the outdoors so much,” said Mary.

Badger wiped a drop of wet cornmeal from the scarred right side of her face. “Why shouldn’t I like it?”

“I don’t mean anything by it, but girls aren’t usually interested in that. Was it something your tribe taught you?”

Badger stopped mixing and stared at the wall.

“I’m sorry,” said Mary. “I shouldn’t have said anything. I’m getting like a nosy old skunk in my old age.”

“No, it’s fine,” said Badger. “I was too young for hunting then. I helped my mother in the fields.”

Mary watched her spin the wooden spoon in the mixture for a few minutes.

“Are you happy?” she asked.

“Happy as I’ve ever been,” said Badger.

“It’s hard to tell sometimes.”

“I don’t ... do well around people. I don’t know what to say. When I’m alone in the forest or on a mountain I don’t have that problem.”

“Is that why you joined the hunters?”

“It was a good a reason as any. Mary, I know I’m not the perfect daughter-in-law. I’m sorry about that.”

Mary put an arm around Badger and hugged her. “No, dear. There’s nothing to be sorry about. As long as the two of you are happy, don’t worry about me or anyone else.”

WILSON DROPPED OFF the rest of the venison with his mother and tried to catch a few hours of sleep. He’d normally be moving to Office where most of the partnered couples stayed, but because of the refugees from the destroyed village there was no space. Luckily the rectory had a few unused rooms and Father Reed had given them permission to clean out one. The grey floor and walls still smelled from the scrubbing soap.

Maybe it was the smell, maybe it was the ceremony the next day, but Wilson couldn’t sleep. He squirmed fitfully under his blankets then finally threw on a jacket and wandered up and out of the underground rectory to the northern part of the village.

Dark peaks surrounded the long valley and protected Station on all sides like pointy-headed priests bowing heads in the moonlight. Unlike the tribal villages in the wilderness or the buildings from the old days, just about all of Station was underground. Concrete mouths in the earth led down to entrance tunnels guarded by massive steel doors. Wide patches of hemp, corn, beans, and vegetable gardens covered the flat land of the valley. In the north lay a large corral and barn for the sheep and goats.

Wilson greeted a few guards on his way to the Tombs. He passed a fence and a rusted sign with only one legible word––“Station.” He descended into a tunnel and pressed a code into an old keypad. The concrete below his feet shook as the metal door slowly ground open.

Inside, crimson light glowed from strips along the walls of a small room. In the center of the floor was a worn metal square edged in yellow and black stripes.

Wilson ignored the panel and walked to a door on the far side of the room. Nearby was another old keypad and a yellowed board with rows of multicolored tags on tiny hooks. He entered the code Jack had given him and walked down a stairwell that spiraled into the earth.

Stepping into the black cistern would have been impossible without a special trick. Wilson concentrated and whispered a poem Badger had taught him.