The Dragons of Winter (35 page)

Read The Dragons of Winter Online

Authors: James A. Owen

Tags: #Fantasy, #Ages 12 & Up, #Young Adult

“And what of your husband, Jason?”

Her face darkened. “My husband is . . . occupied elsewhere. I don’t expect that he shall return soon, if at all.”

“A queen should not be walking thus, unattended and alone,” said Rose. This was closer to her own era, Bert knew, so the mannerisms and proper courtesy to royal blood came more easily to her.

“My chariot was damaged crossing the Frontier,” Medea answered. “Only one of my Dragons chose to attend me after . . . a dispute with my husband. And her strength was insufficient to weather the storms as smoothly as with both. One of my shipbuilders is down the beach,” she said, pointing, “but I fear it’s beyond his skill to repair.

“A shame to have to have him killed,” she added. “He did build good ships.”

“The chariot,” Bert murmured to the others. “That’s how it was done, before Ordo Maas built the Dragonships. The Dragons personally escorted Jason and Medea to the Archipelago, through the Frontier.”

“I have experience at a forge,” Edmund said bluntly. “I could effect the repairs your chariot requires.”

Medea’s eyes brightened for a moment, then dimmed in distrust. “At what cost?”

“A boon,” Edmund said evenly. “I shall do you this service, and you’ll owe me one in return.”

She shook her head. “That’s too high a price,” she said haughtily, tossing her head and folding her arms. “Still . . .” She thought a moment, glancing now and again at Rose’s bracelets.

“Agreed,” she said finally—to Rose, not Edmund. “But if your servant is unable to fix it to my liking, then you and all your servants will stay on Autunno to serve me, until I choose to release you.”

Rose bowed. “We have a bargain.”

Medea turned and strode down the beach. Quickly the companions gathered their things and followed her.

“You’re not offended to be called ‘servants’?” Rose asked her companions, smiling.

“I’ve been there before,” Charles replied. “I’m just happy she didn’t call me ‘Third.’”

The stables were well-appointed and had all the materials necessary for Edmund to reshape Medea’s chariot.

“I can do this,” he whispered to Rose, “but just the same, I’d give almost anything to have your father with us for the next few hours.”

“You’ll do fine,” Rose reassured him, “and for what it’s worth, so would I.”

“I didn’t know he’d been trained as a blacksmith,” Charles remarked. “I thought he came from a line of silversmiths.”

“He wasn’t trained by a smithy,” Rose said, grinning. “He was trained by a scientist—Dr. Franklin. That may not mean much in twentieth-century Oxford, but in ancient Greece, it makes him a Magic Man.”

The young Cartographer set to work, and in short order had

restructured the chariot to be pulled by a single creature instead of two.

“You did that rather easily, and quickly,” Medea said as she looked over his handiwork. “Impressive. Perhaps too impressive. I think that maybe I bargained too quickly, Master Smith.”

“I said I could do it, and I have done it,” he replied, wiping his brow with a cloth.

“And far more quickly than that fool Argus,” she said. “If I’d left him to it, he’d have taken a week, and the wheels would still rattle.”

“Your shipbuilder’s name is Argus?” Edmund asked, as casually as he could manage. “As in, the man who built the

Argo

for Jason and the Argonauts?”

“Yes,” she said, face darkening. “Why?”

He set the cloth aside. “That is the boon I ask. Spare his life.”

“What are you doing?” Rose whispered.

“I know what she did to her sons,” Edmund whispered back. “She’s a really horrible person, and so I asked for the one thing I know will twist her in knots to grant me.”

Rose was surprised by Edmund’s request, but nonetheless nodded her agreement. “That is our request,” she said to the queen. “Spare the shipbuilder Argus.”

“A boon is a boon,” said Medea, “but this is more. This is blood. By what right do you ask a life-boon?”

Rose glanced back at Edmund, who folded his arms defiantly. “By right of blood—blood ties of family, great-grandmother,” she said softly, her voice low and cool, but with a trace of menace nonetheless. “A bond that cannot be taken, only given.”

Medea did not understand what she meant by these

words—and had no way of knowing that Rose was descended from the bloodline of the Argonauts. But it was Edmund’s handiwork on the chariot that gave her pause. This youth was no mere servant. He was clearly a Maker—and thus, not to be trifled with. That the young woman who bore the ornament of royalty also claimed a blood-bond told Medea she should not overplay her hand.

“Agreed,” she said, and made as if to leave, but paused in the doorway of the stables.

“Interesting that this should be your request, today of all days,” Medea said.

“Why is that?” asked Rose.

Medea shook her head. “Just coincidence, or perhaps . . . fate,” she answered. “He was to be killed in service of another blood-debt, which is still owed. But no matter—I gave you my word. And the word of a queen of Corinth is sacrosanct.

“The regent of the Old World will be arriving soon, and I must prepare for him. The shipbuilder will be freed, as you have asked.”

The queen of Corinth left the stables, and a few moments later they saw she was good to her word, as a young, rather ragged man appeared at the doorway.

He looked curiously at the strange band of travelers, then walked over to Edmund and offered his arm, in the old Greek tradition.

“I understand you are the one who is responsible for my good fortune,” Argus said slowly, “and I find I have no words to . . .”

Edmund took his arm. “A boon was given for your life,” he said. “Perhaps someday, you’ll do the same for another.”

Argus stepped back and bowed. “I will. You have my word—although my skills are rarely called upon these days. Few adventurers are bold enough to hire a shipmaker who can bind the spirit of living creatures into a vessel.”

The companions all stilled at hearing this.

“Have you ever bound a Dragon to a ship?” Bert asked. “Could you, if someone wished it done?”

Argus laughed. “I have the skill, but no one will ask me to,” he said. “Not while my master is still working in the trade. His are far better than mine.”

“Who is your master?”

“The greatest of all shipbuilders,” Argus replied. “Ordo Maas.”

A bright gleam suddenly appeared in Bert’s eyes. “Does anyone else have this skill other than yourself and Ordo Maas?”

Argus folded his arms and shook his head, grinning. “None living, or otherwise. Only he and I.”

“That’s awfully self-assured,” said Charles.

“Not at all,” said Argus. “Merely the truth.”

“That’s the boon,” Bert said suddenly, glancing at Edmund, who looked startled, but nodded his assent. “Someday, perhaps many years from now, someone will ask you to build such a ship. All we ask is that you do it.”

“Done and done,” Argus said in surprise. “And a bargain at twice the price.” He stretched his back and turned to the doorway.

“Again, you have my gratitude,” he said. “I have to go find my master—but I shall always remember. Call on me if you are ever in need. And when the time comes, I’ll build your ship.”

With that, he trotted off down the beach.

“What was that all about?” Charles asked. “What Dragonship did you want him to build, Bert?”

“One that in our time, he’s perhaps already built,” Charles’s mentor replied. “A ship that only Ordo Maas could have built, but didn’t. A ship that no one living knows the origin of. A ship,” he added, looking pointedly at Rose, “that has been at the heart of one of the great mysteries of the Archipelago.”

Charles gave a low whistle. “Do you really think so, Bert?”

“I do,” Bert said, nodding. “I think we’ve just saved the life of the man who will build the

Black Dragon

.”

Before the companions could discuss this extraordinary turn of events further, another voice called out from the darkness at the far end of the stables. It sounded inebriated.

“Was that the shipbuilder, Argus?” it called out. “I was s’pposed t’ kill him today. Blood-debt, you know.”

Cautiously, Edmund picked up an iron bar, as did Charles, and they motioned for the others to stay back. “Who goes there?” Charles called out.

“I’d say it’s the Comedian, but the Comedian is dead,” said the voice. It was coming from the far stalls, away from the entrance, where the torchlight didn’t reach.

“I’d say it’s th’ Philosopher, but the Philosopher is terrible at Philosophizing,” the voice rambled on. “So I must be th’ Executioner—’cept you just freed the executionee, so I think I’m out of a job again.”

As he spoke, they heard another sound—rattling chains. He was not a servant of Medea, but a prisoner.

“You sound very familiar to me,” Charles said. “Something in

the tenor of your voice—I’ve heard it somewhere before. Did you say you were a philosopher?”

“I did, but I don’t mind telling you again,” came the answer. “I

was

a philosopher. Of some renown, I might add, although of late”—he clanked his chains for emphasis—“I seem to have fallen into disfavor with th’ queen. Again.”

“Ah!” Charles said as he and Edmund lowered the iron bars. Whoever this drunkard was, he was no danger to them. “A learned man, then.”

“A learned man who’s just been sick all over his sandals,” said the voice.

“Mmm, sorry,” said Charles. “I’m Charles, by the way, and these are my friends Rose, Bert, and Edmund. Despite the circumstances, we’re very pleased to make your acquaintance.”

“And I you,” the voice replied. “My name is Aristophanes.”

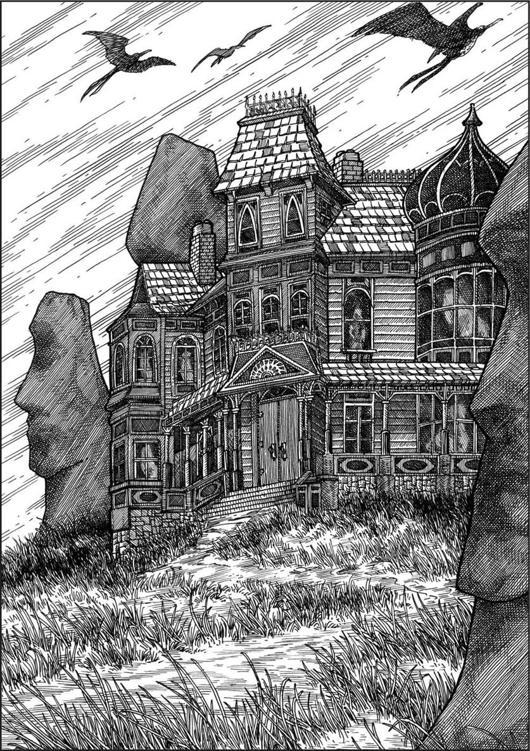

Standing at one of the tall windows . . .

the Chronographer of Lost Times waited . . .

The flight from the Goblin Market

was marked by both the speed Uncas was driving, and the nearly endless stream of curse words being generated by the Zen Detective. Apparently, he was fluent in over a dozen languages—at least, fluent enough to competently curse.