The Dragonfly Pool (5 page)

Read The Dragonfly Pool Online

Authors: Eva Ibbotson

“Who is she? ” asked Tally.

“She's called Clemency Short. She teaches art and she helps out in the kitchens. She's a marvelous cook.”

“I thought I'd seen her before, but I can't have done.”

“Actually you can,” said Barney. “She's in the London Gallery as the Goddess of the Foam, coming out of some waves, and on a plinth outside the post office in Frith Street standing on one toeâonly that's a sculpture.”

“And on the wall of the Regent Theater as a dancing muse,” said Julia. “She looks a bit cross there because the man who painted the mural was a brute and made the girls stand about in the freezing cold dressed in bits of muslin, and Clemmy got bronchitis. That's what made her decide to stop being an artist's model and become a teacher.”

It was a long journey. The children brought out their sandwiches; they grew drowsy. Julia had stopped turning the pages of her magazine. Tally thought she might be asleep, but when she glanced at her she saw that she was looking intently at one particular picture: a photograph of a woman with carefully arranged curls drooping on to her forehead, a long neck, and slightly parted lips. The caption said: “Gloria Grantley: One of the loveliest stars to grace the firmament of film.”

“Isn't she beautiful? ” said Julia, and Tally agreed that she was, though she didn't really care for her. Gloria looked hungry, as though she needed to eat an admiring gentleman each day for breakfast.

The train stopped briefly at Exeter and Clemmy came past again, checking that everybody was all right.

“By the way, you're in Magda's house,” she told Tally. “And Kit, too. Julia will show you; she's with Magda, too.”

“Oh dear, that's bad news,” said Julia when Clemency had gone.

“Isn't she nice? Magda, I mean.”

“Yes, she's nice enough. Kind and all that. But she feels bad about things, and her cocoa is absolutely diabolical.”

“Cocoa can be difficult,” said Tally. “The skin . . . but why does she feel bad? ”

“She teaches German and she used to spend a lot of time in Germany, and every time Hitler does something awful she feels she's to blame. She's really a philosophy studentâshe's writing a book about someone called Schopenhauerâand her room gets all cluttered up with paper and she can't sew or sort clothes or anything like that.”

“Perhaps we could help her to make proper cocoa,” said Tally. “She probably needs a whisk.”

But Kit had gone under again.

“I don't like cocoa with skin on it,” he began. “I want to go to a proper school where they . . .”

But just then the train gave an unexpected jolt and a shower of water from Barney's axolotl descended on his head.

When they had been traveling for more than three hours Tally looked out, and there was the sea. Tally had not expected it; the sun, the blue water, the wheeling birds were like getting a sudden present.

They went through a sandstone tunnel, and another one . . . and presently the train turned inland again. Now they were in a lush green valley with clumps of ancient trees. The air that came in through the open window was soft and gentle; a river sparkled beside the line.

The train slowed down.

“We're here,” said Barney.

“Really? ” said Tally. “This is Delderton? ”

Her father had spoken of the peaceful Devon countryside, but she had not expected anything like this.

“My goodness,” she said wonderingly. “It's

very

beautiful!”

very

beautiful!”

CHAPTER FOUR

Delderton

T

ally was right. There was no lovelier place in England: a West Country valley with a wide river flowing between rounded hills toward the sea. Sheltered from the north winds, everything grew at Delderton: primroses and violets in the meadows; pinks and bluebells in the woods and, later in the year, foxgloves and willow herb. A pair of otters lived in the river; kingfishers skimmed the water, and russet Devon cows, the same color as the soil, grazed the fields and wandered like cows in Paradise.

ally was right. There was no lovelier place in England: a West Country valley with a wide river flowing between rounded hills toward the sea. Sheltered from the north winds, everything grew at Delderton: primroses and violets in the meadows; pinks and bluebells in the woods and, later in the year, foxgloves and willow herb. A pair of otters lived in the river; kingfishers skimmed the water, and russet Devon cows, the same color as the soil, grazed the fields and wandered like cows in Paradise.

But it was children, not cows or kingfishers, that Delderton mainly grew.

Twenty years earlier a very rich couple from America came and built a school on the ruins of Delderton Hall, with its jousting ground and ancient yews, and they spared no expense, for they believed that only the best was good enough for children, and they were as idealistic as they were wealthy.

The new Delderton was built around a central courtyard; the walls were lined with cream stucco; the windows had green shutters; the archway that led into the building was crowned by a tower with a blue clock adorned by gold numbers and a brilliantly painted weather vane in the shape of a cockerel.

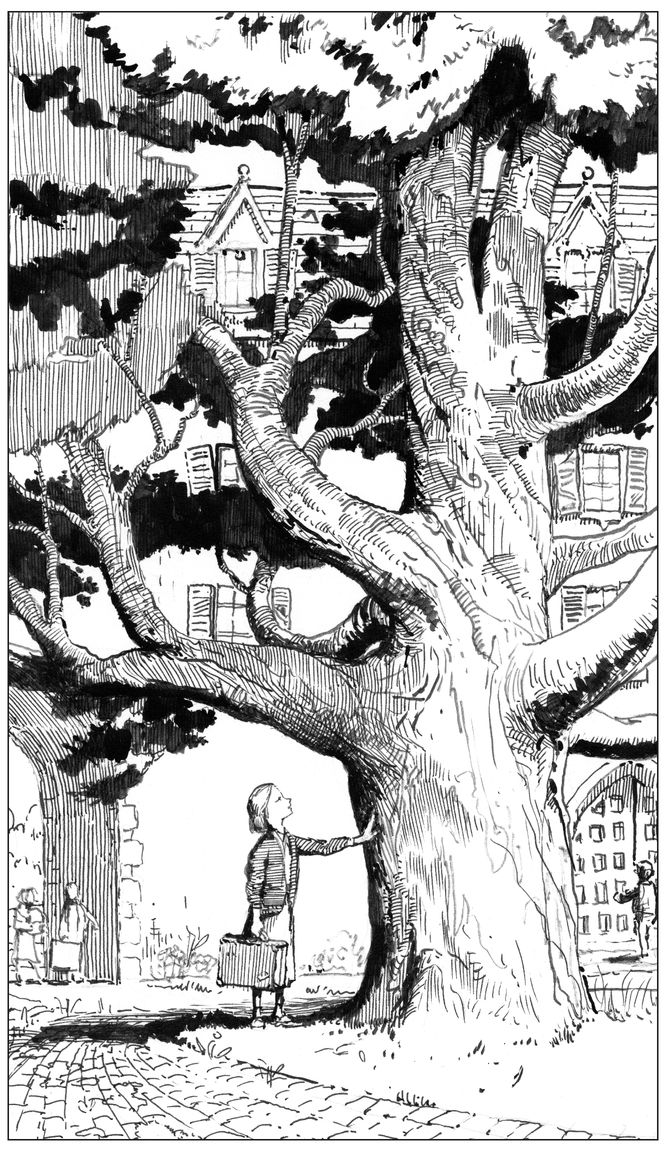

And the ancient cedar that had sheltered the lawns of the old hall was saved and grew in the center of the courtyard.

Inside the building, too, the American founders spared no expense. Each child had its own room: only a small one, but private. The common rooms had well-sprung sofas, the pianos in the music rooms were Steinways, and the library housed over ten thousand books.

But what was important to the founders was not the building, it was what the school would mean to the children who came to it. For Delderton was to be a progressive schoolâa school where the children would be free to follow their instincts and develop in a natural way. There would be no bullying or beatings, no competitive sports where one person was ranked above another, no examsâjust harmony and self-development in the glorious Devon countryside. A school where the teachers would be chosen for their loving kindness and not their degrees.

And this was exactly what had happened. But now, twenty years later, the building looked . . . tired. The cream walls were streaked with damp from the soft West Country rain; the paint on the shutters was flakingâand the beautiful cedar in the courtyard was supported by wooden props.

And the nice American founders were tired, too. In the autumn of 1930 they sold the school to a board of trustees who appointed a new headmaster. His name was Ben Daley: a small, portly man with a bald head and a nice smile, who now, at the beginning of the summer term, was looking out of his study window at the pupils coming in through the archway from the station bus.

And at one pupil in particularâa new girl with straight fawn hair who had stopped and laid her hand on the trunk of the cedar as though she was greeting a friend.

“It's three hundred years old,” said Julia, looking up at the tree. “The headmaster's mad about itâif anyone climbs it or throws stuff into the branches he comes rushing out of his room. No one ever gets expelled here, but if they did it would be because of the tree. That top branch broke off because a horrible boy called Ronald Peabody climbed it, though it was already weak. He fell and broke his arm, but nobody cared.”

“I wouldn't have cared either,” said Tally.

The rooms where the children slept were on corridors on either side of the courtyard. Inside, the building was divided into four houses separated by double doors. Each house had a room for the housemother, a common room, and a pantry. Tally was in the Blue House; her room overlooked the courtyard and the tree.

“You mean we each have our own room? ”

Julia nodded. “I don't know for how much longer; I think the money's running out a bit, but for now.”

Tally's room was very small, but it had everything you could want: a divan bed, a washbasin, a bookcase, and a built-in wardrobe. The door of the wardrobe was somewhat battered and one desk leg was propped up on a wedge, but Tally was delighted. And it solved at once the problem of the feasts in the dorm. No one could have a feast in a dorm which was not there.

Julia was in the room next to hers; then came Barney, then two children she had not met yet. Kit was at the far end of the corridor.

As she was putting her things away there was a knock on the door.

“Do you need any help with unpacking? I'm Magdaâyour housemother.”

Magda was thin and very dark with large black eyes and wispy hair.

Tally shook her head. “No, I'm all right, thanks.”

“Good. Well, high tea's in half an hour. You'll hear the gong. And after that you're to go along to the headmaster's room.”

Tally looked stricken. She had not quite shaken off the memory of the books she had read before she came. “I can't have done anything yetâI've only just got here.”

Magda smiled. “No, no. Daley likes to welcome new children individually. Julia will show you where to go.”

The headmaster's study was large and light. One window looked out over the courtyard; another faced the terraced garden leading to the playing field and, beyond it, the rolling hills. Now, hearing a quiet knock at the door, Daley said, “Come in,” and a girl with a nibbled fringe and interested eyes came into the room.

Other books

The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon by Richard Zimler

Amaryllis by Nikita Lynnette Nichols

Essential Master (Doms of Napa Valley) by Trace, Dakota

High Risk by Carolyn Keene

Forbidden Flowers by Nancy Friday

A Soldier' Womans by Ava Delany

Adelaide Confused by Penny Greenhorn

Innocent Blood by David Stuart Davies