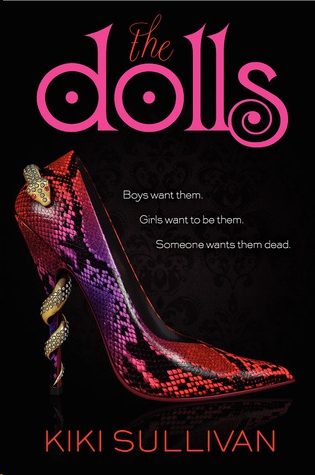

The Dolls

Authors: Kiki Sullivan

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #People & Places, #United States, #General, #Fantasy & Magic

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

Advance Reader’s e-proof

courtesy of

HarperCollins Publishers

This is an advance reader’s e-proof made from digital files of the uncorrected proofs. Readers are reminded that changes may be made prior to publication, including to the type, design, layout, or content, that are not reflected in this e-proof, and that this e-pub may not reflect the final edition. Any material to be quoted or excerpted in a review should be checked against the final published edition. Dates, prices, and manufacturing details are subject to change or cancellation without notice.

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

TO JAMES, CHLOE, EDDIE, AND COLTON:

I CAN’T WAIT TO SEE WHO YOU GROW UP TO BE.

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

W

hen I open my eyes and blink into the milky morning sunlight, there’s no longer snow on the ground outside the car. Instead of the brown-gray tableau of a New York winter, endless cypress trees line the road, their branches heavy with Spanish moss and their green leaves catching the first rays of dawn.

As I struggle upright from a deep slouch in the passenger seat, it takes me a second to remember exactly where we are: Louisiana—or en route to Louisiana, anyhow. I’d fallen asleep just before midnight some eight hundred miles into our drive. Now, just after six a.m., thick white fog swirls around us, making it seem like we’ve been swallowed whole by a silent, drooping forest.

“Good morning,” I croak, unwinding a tangle of red hair from my watchband.

“Morning, sleepyhead,” Aunt Bea replies without turning. She’s focused intently on the road ahead as if expecting cross traffic, though the woods appear entirely deserted. “Did you sleep okay?”

I glance at my watch. “I guess I did,” I say. “How are you feeling?” She’s been awake for at least a day, running on coffee and Red Bull.

“I’m hanging in,” Aunt Bea says, her face taut with exhaustion. “We’ll be there soon.”

“Cool.” I try to smile, but it comes out as a grimace. I still don’t understand why we’re doing this.

Three days ago, my life was normal: winter break was almost over, and I was getting ready to celebrate my birthday and start the second semester of junior year. Then Aunt Bea—my legal guardian since I was three—announced over coffee and Cheerios that we were moving back to Carrefour, Louisiana, the town we left fourteen years ago right after my mom killed herself.

“I miss Brooklyn already,” I murmur as I look out the window again.

“Give Carrefour a chance, Eveny. Believe me when I say you’ll fit in fine.”

“You don’t know that.” The thing is, I’ve always felt a half step different from everyone else, more at home in gardens and with plants than with real people. Still, I managed to develop a small, tight-knit group of friends back in New York. Starting over feels daunting.

“Carrefour isn’t exactly new to you,” Aunt Bea says, reading my mind. “People will know who you are.”

“That’s what I’m afraid of: being the girl whose mom offed herself by driving into a tree.”

“Oh, Eveny,” Aunt Bea sighs, “no one’s going to judge you for that. If anything, they’ll feel bad for you.”

“I definitely don’t need anyone’s pity.” After all, my memories of my mom are all good ones—up until the day it all ended.

“You know, it’s okay to let people in,” Aunt Bea says after a pause. “Your mom being gone is still hard for me too. But you deserve to know who she really was. I think being in Carrefour, where people knew her, will be a good thing.”

She looks miserable, so I force a smile and say, “Moving back will be good for you too.”

Aunt Bea’s been dreaming for years about opening her own bakery, but in New York she could never afford to do it. In Carrefour, she’ll be leasing a kitchen space downtown and is already making plans to open within the next week and a half. As frustrated as I am about this move, it will be positive for her, at least. And that’s something.

I take a deep breath and add, “If you think this is the right thing, I’m on board.” I spend the next hour of the drive trying to convince myself the words are true.

It’s 8:46 in the morning and I’m texting with my best friend Meredith when Aunt Bea announces, in a voice that sounds oddly choked, that we’re almost there.

I look up in surprise as we approach an impenetrable-looking iron gate. On either side, as far as I can see, a stone wall ten feet tall extends into the swampy forest. Above the gate is a rusted sign that says

Carrefour, Louisiana: Residents Only

in swirling script.

“Residents only?” I ask. “How are we going to get in?”

“We’re residents, Eveny.” Aunt Bea shifts the car into park and steps out into the foggy morning. She rummages in her purse for a moment before pulling out an antique-looking bronze key. She inserts it into an ornate keyhole and hurries back to the car just as the gate begins to creak loudly open.

“What the . . . ?” I say, my voice trailing off as she gets in and begins driving through. I turn around and watch as the gate closes slowly behind us, its hinges squealing in protest. “What

was

that?”

“My key to Carrefour,” she says, like it’s the most obvious thing in the world. “It’s passed down from generation to generation, and every family has one. It’s the only way in or out.”

“Weird,” I murmur. We continue through a swampy area that gets darker and darker as more tangled branches stretch overhead. Mist is rising from the shallow water surrounding the road, and as we break through a clearing, my confusion deepens. I thought I’d recognize Carrefour right away, but this place doesn’t look at all familiar.

The town that lives in my memories is Southern, Gothic, and filled with old mansions and stately, moss-draped cypress trees. But what’s rolling by my window is a lot plainer than that, making me wonder if I’ve imagined everything. Bland row houses line the paved streets, and kids play in a few of the yards. I see a yellow car jacked up on bricks in front of one of the homes and a cluster of plump, middle-aged women wearing dresses and wide-brimmed hats sitting on a front porch of another. A tangle of little boys kicks a soccer ball lazily around the end of a street, and two girls ride rusted bikes in circles at the end of a cul-de-sac.

“This is Carrefour?” I ask.

“

Technically

, yes,” Aunt Bea responds. “But you didn’t spend much time out here in the Périphérie.”

The name rings a vague bell, but I can’t place it. Behind the row houses, I glimpse marshy wetlands, gnarled cypresses, and a pale green film on the surface of what appears to be a stagnant creek. Spanish moss hangs from hickory branches that arch over the road like a canopy. Above them, the sky swirls with the dark clouds of a coming storm.

I look out the window again, feeling a little sad. “I just don’t remember the town looking like this.” Not that I’m judging. I loved the cluttered disarray of Brooklyn. But I’d always thought of Carrefour as so opulent—and so wealthy.

“This was always the . . . less privileged area of Carrefour,” Aunt Bea says, her brow creasing. “But it seems like it’s gotten a whole lot worse since we left.”

“Bad economy?” I guess as the road leads us past the last dilapidated house and into a deep, misty forest.

“Maybe,” she says slowly. “But I’d be willing to bet central Carrefour is doing just fine.”

As we round another bend and emerge from the woods, sunlight suddenly streams in from all directions. In under a half mile, we’ve driven into an entirely different world.

Just beyond the final creeping cypress tree of the Périphérie sits the edge of the most perfect-looking town I’ve ever seen. As we begin making our way through a neighborhood, I see immaculately manicured lawns, houses with picket fences and matching shutters, and gardens blooming in brilliant color even though it’s January. “It’s like one big country club,” I say.

I stare out the window as Aunt Bea takes a left, turning into what appears to be Carrefour’s downtown area. On the corner there’s an ice cream parlor flanked by a café with an old-fashioned enjoy a coke sign out front, and beside it a little French bistro called Maxine’s. A half-dozen shops that look like they belong in an Atlantic seaside resort town—not middle-of-nowhere Louisiana—extend down the left side of the street.

“That’s where my bakery will be,” Aunt Bea says, pointing to a sliver of storefront next door to a boutique called Lulu’s. “It used to be a little walk-up hamburger stand when your mom and I were kids.”

Perfect canopies of blue and white stripes shade the sidewalks of the main street—which is actually called Main Street—and the store windows are all cloaked in curtains of sea foam green and pale yellow. The buildings are a uniform clapboard white, and the people strolling along look like they’ve been plucked from Martha’s Vineyard and dropped here in their shirtdresses, khakis, and button-down shirts.

“They know it’s winter, right?” I ask as I watch two women emerge from the market with a wicker picnic basket. “And that they’re not actually on their way to a clambake?”

Aunt Bea laughs. “Roll down the windows. It won’t feel like winter here.”

I give her a skeptical look, but by the time my window is halfway down, I realize that it must be in the low seventies outside. “But it’s January,” I say.

“It’s Carrefour,” she says without explaining.

“Does everything here look like a postcard?” I ask, wriggling out of the sweatshirt I’ve been wearing since we left New York.

“Wait until you see our house,” she says, and, suddenly, I feel uneasy. The last clear memory I have of this town is standing in our front hallway with my mother’s two best friends, Ms. St. Pierre and Ms. Marceau, as the police chief arrived to tell me the news.

Honey, your mama killed herself

, he’d drawled.

Drove right into a tree

. I’d screamed and screamed until I passed out.

“There’s your school.” Bea cuts into my thoughts as we pass a sprawling brick building with an ornate sign that reads

Pointe Laveau Academy

in Victorian script, just like the entrance gate. The parking lot is full of expensive sports cars, and two impossibly thin girls in white oxfords, maroon plaid skirts, and knee socks walk across the lawn, deep in conversation.

“Isn’t there a public school in town?” My skin itches just thinking about wearing a uniform, never mind fitting in with a bunch of rich kids.

“There is,” Aunt Bea answers lightly, “but your great-grandmother founded Pointe Laveau Academy, and it’s where your grandma, your mom, and I went.”

I’m about to argue, but then I look out the window and realize the sun has slipped behind the clouds, casting long, eerie shadows over the cemetery we’re about to pass on the edge of town. Suddenly, a vivid memory hits me like a punch to the gut.

It’s my mother’s funeral, and I’m standing amongst soaring white tombs, my eyes sore from crying. A man with sandy hair and dark sunglasses slips from the shadows and bends to speak to me, his voice low, his words fast. “You must listen to me, Eveny, I don’t have much time.” He’s a stranger, but there’s something familiar about him. “They’re coming for you. You have to be ready.” He melts back into the shadows before I can ask what he means. . . .

I gasp and push the image away as I try to catch my breath.

Aunt Bea looks at me sharply. “What’s wrong?”

“Nothing,” I say. “Just a weird memory.” I hesitate. “Of Mom’s funeral.”

“Honey, you were only three then,” Aunt Bea says gently. I don’t think I’m imagining the concern on her face. “What are you remembering?”