The Dog Who Could Fly (26 page)

Read The Dog Who Could Fly Online

Authors: Damien Lewis

Tags: #Pets, #Dogs, #General, #History, #Military, #World War II, #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical

Tonight’s target was the tank factory M.N.H. Maschinenfabrik Niedersachsen, one of Germany’s most important plants making tracked armored vehicles, including the fearsome Panther medium main battle tank, and the

Jagdpanther

—hunting panther—tank killer. Using the River Leine as a visual marker, the flight of Wellingtons thundered in toward the city’s industrial district, but the flak that blossomed ahead of them was the most fearsome yet. It appeared as a towering inferno thrown before the aircraft, the black bursts of the explosions lit here and there a fiery orange by detonating shells and bursts of tracer fire.

As with the aircraft ahead of him, C for Cecilia’s pilot, Capka, was forced to fly evasive action, throwing the heavily laden aircraft into a series of turns as he tried to thread a course through a seemingly impenetrable wall of explosions and arrive over the target. As the Wellington lurched this way and that, Robert reached down to caress the ears of his dog in an effort to comfort him. He had his eyes glued to the heavens above, in case an enemy fighter might dive to attack, but few German pilots were likely to risk doing so when the flak was so thick.

Robert himself had no idea how they made it through the flak unharmed. Their bombs released, Capka banked away from the monstrous storm of high explosives and jagged shrapnel that rent the skies all around them. But C for Cecilia had been driven off course as a result of all the twists and turns she’d been forced to make, and the needles of the fuel gauges showed the juice was running low. In level, straight flight and at normal cruise speed the Wellington’s fuel consumption was manageable, but flying such maneuvers as Capka had been forced to make, and at close to their top speed, he had burned up the gas.

C for Cecilia crossed the British coastline three-quarters of an hour behind their flight schedule, testament in itself to how far they’d erred from their intended course. Every turn of the aircraft’s twin radial engines brought her nearer to their base, but at the same time sucked up the remaining fuel. Capka had to land the warplane at their East Wretham base by the most direct and quickest route possible. There was one major problem: as he pushed northward, the entire expanse of East Anglia turned out to be blanketed in thick fog.

As the first rays of dawn flared over the pencil-thin horizon, the aircrew gazed down upon a scene that under different circumstances would have appeared quite magical. Golden rays of sunlight lit up the rolling cotton wool of the fog bank in a thousand shades of pink and orange. But few of the crew had eyes or thoughts for how beautiful the summer mist might look: the fog lay to a height of six hundred feet above ground level, and it spread to the far horizon in every direction. There was no way they could land at RAF East Wretham—or any other base within their sight—and the fuel gauge was flickering on zero.

Capka’s voice echoed over the aircraft’s intercom as he calmly informed the crew of their predicament. It had been fairly obvious to all, even without their captain laying it out for them. Robert glanced

at the dog sleeping peacefully at his feet. As was Antis’s wont on such sorties, once their aircraft had turned for home—bombs gone—he seemed to sense that the worst of the night’s adventures were over, and went to sleep.

“I’ll fly a holding pattern and keep trying to speak to control,” Capka informed them. “Stand by.”

Robert felt the Wellington shift course imperceptibly, and he sensed Capka had put her into a graceful turn. For twenty minutes the aircraft circled the airbase as Capka kept radioing East Wretham. For all he knew, the fog might be clearing at ground level as the dawn rays burned it off, and a landing might just be possible. Trouble was, he couldn’t seem to raise anyone. Dawn and dusk were never the best times to try to make radio contact, due to the fast-changing atmospheric conditions at those times of day, which tended to interfere with radio communications.

When Capka finally managed to get through, he was told the Met forecast was for no change, at least not for the next hour or so. The Watch Office at East Wretham had been firing Very lights at regular intervals, and if none had been spotted by C for Cecilia’s crew, that proved how thick and impenetrable the fog must be. Unfortunately, conditions were equally bad at neighboring airfields.

As all the crew were plugged into the aircraft’s intercom, they’d all heard the bad news. They also heard the final order given to Capka.

“Climb to ten thousand, set a course for the coast, and abandon your aircraft. Good luck.”

The logic behind the order was simple. Ten thousand feet was the optimum height at which to abandon an aircraft: it would give the Wellington plenty of glide altitude, more than enough to ensure it was over the waters of the North Sea before it crashed. It was also about the maximum altitude the crew could parachute from without needing breathing equipment. If they bailed out, the aircrew would most likely live, but they’d sacrifice their aircraft. New Wellingtons

were churning off the production lines daily: it was finding crews to fly them that was the real challenge, especially with the attrition rates suffered by squadrons like their own.

All of that made perfect sense apart from one thing: they had a canine crew member, and no one had thought to make a parachute for their dog.

Eighteen

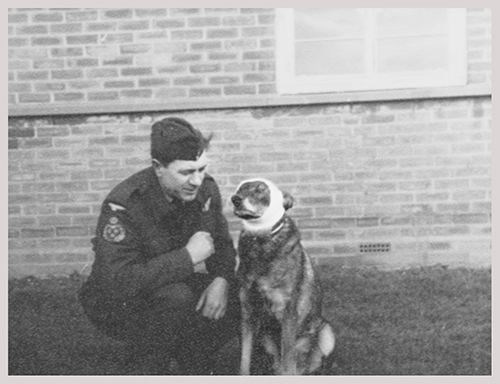

Finally, Antis refused to remain behind when his master flew into war and stowed away on his aircraft—facing bailing out, crash landings, and worse.

N

one of the crew of C for Cecilia had ever bailed out. It wasn’t Air Ministry policy to give the crews of Bomber Command more than a basic grounding in the theory of parachuting. Robert had gotten East Wretham’s tailor to make some further adaptions to his dog’s oxygen mask, so it fitted as snugly as a sock now, but he was beginning to wonder if he shouldn’t have asked the parachute section to make Antis a doggie parachute.

Whatever, it was too late to worry about it now, and there was no way that Robert was about to bail out without his dog. If he went they

both went, and he could only imagine he’d have to jump with a terrified dog clutched in his arms—though how he’d be able to pull his chute and steer it while holding on to his dog he didn’t have a clue.

Robert had never felt so anxious in all his hours of flying. As for Antis, he dozed on, oblivious to the danger, his head resting on his forepaws on the cold metal floor.

“Starting to climb to ten thousand,” Capka reported to control. “I’m heading due east for the coast, fuel gauge on the absolute minimum reading possible.”

In reply, a new voice came up on the radio net. “Not to worry, Jo,” their squadron leader intoned. Bearing in mind the circumstances, Wing Commander Ocelka seemed as cool as a cat. It was heartening. “If your indicator’s at zero you’ve still got some twenty gallons in the tanks. Should be enough to get you near the coast and up to ten thousand. There’s no point trying a landing in the thick muck that’s down here, so you’re better off bailing.”

“I could try to put down,” Capka suggested.

“It’s your call,” Ocelka replied, “but I don’t advise it.”

The radio traffic went dead for a second as Capka eased the bomber into a shallow climb. In the blinding dawn light Robert spotted the glint of an aircraft away to their right. For a moment he tensed his shoulders and prepared to swing his guns around to face the threat, before recognizing the four-engine aircraft for what it was—a Stirling heavy bomber. As he watched, the first of a series of seven parachutes bloomed beneath the aircraft as the Stirling’s crew did what C for Cecilia’s aircrew were about to attempt. The Stirling, set on automatic control, continued on its steady course flying eastward out to sea.

Josef’s voice came up on the intercom. “There’s a Stirling to starboard and they’ve all jumped.”

“Must have got similar orders to us,” Capka remarked calmly. “I’ve set a course east and we’re climbing, but what d’you all want to do?”

Several voices—Robert’s first and foremost—responded with the same answer.

“Try for a crash landing, skipper.”

They knew their pilot well, and other than “old man” Ocelka himself he was the best in the squadron. If anyone could get them down in one piece, Capka could. They were also loath to abandon C for Cecilia, the trusty Wellington having brought them home from so many sorties when by rights she should have been a goner.

“Mr. Karel?” Capka queried. “D’you think we can make it?”

Capka, a sergeant, always called their navigator, Karel Lancik, “Mr.,” in deference to his officer status, three officers and three sergeants making up the Wellington’s crew.

“Try for a crash landing at Honington,” Karel replied calmly. “It’s only five miles away, so we should make it. Glide the last bit if you have to. You know Honington like the back of your hand, and maybe she’ll be a little more fog-free.”

“Sounds like a plan to me,” Capka remarked. “What’s the heading, Mr. Karel?”

As Karel worked out the bearing for RAF Honington, Robert reflected upon the elephant in the room, as it were, which was Antis. No one had said as much, but all six of the aircrew knew that if they bailed, Robert and his dog would have to jump together, and if Antis panicked both of them stood next to no chance of making it. Like the rest of them, Robert had never even done a practice jump, let alone rehearsed for doing one with the flying dog of war grasped in his arms.

“Warning light’s on for zero fuel,” Capka intoned. “You have that bearing?”

“Zero eight seven degrees,” came Karel’s reply.

“Zero eight seven,” Capka confirmed. “Everyone, brace for a rough landing, and Robert, get that dog in your lap and hold on tight. Once we’re down, all out as fast as we can, dog included—”

“I can’t raise Honington,” the copilot’s voice cut in. “Try reaching them via East Wretham.”

“I’m trying for a landing at Honington,” Capka radioed Ocelka. “Can you radio through a warning—”

“Got it,” Ocelka cut in. “I’ll deal with it. You concentrate on getting down in one piece, dog and all! Stand by.”

The seconds ticked by in a tense silence. Robert could feel the Wellington coming around onto its new bearing, and he sensed the aircraft losing height. He doubted whether they had enough fuel in the tanks to fill a cigarette lighter, but from this altitude they should be able to glide the five miles in, as Karel had suggested. The problem with doing a glide approach was that it left zero room for maneuver, which was bad enough in full visibility. It was close to suicidal when going in completely blind.

Robert reached for his dog, grabbed his thick metal collar, and gave his head a good shake. “Antis! Antis! Wake up!”

Antis opened one sleepy eye, heard the reassuring drone of the twin engines, and tried to settle back down to sleep again.

“Wake up!” Robert shook him some more. He leaned back from his guns and presented his lap. “Hup! Hup! Hup!”

For a second Antis eyed him in confusion. He knew the rules: flying was a deadly serious business and the last thing he or his master ever did was fool around—yet here he was being invited onto his master’s lap! Maybe Robert was about to teach him to use those long, noisy pointy things, the ones that his master used to scare off the enemy? Either way Antis was being ordered to get up, and get up he would. He took a leap, landed in Robert’s lap, and sat there half smothering him.

“Honington’s unusable.” Ocelka’s voice came back on the air. “Fog’s down like pea soup. But if you want to give it a try they’ll do what they can. Watch out for a red at the beginning of the only runway they think you might get down on. Good luck.”

“Roger,” Capka confirmed. “We’ll try for the landing.” He switched to the intercom. “As you heard, we’re going down. Brace yourselves, and hold tight to that dog!”

Moments later the air around the Wellington grew dark as she plummeted into the fog. Robert’s gun turret was surrounded by a soggy gray-whiteness, like a fishbowl packed around with cotton. He hugged his dog closer, bracing for the impact that would tear Antis from his arms and throw him forward into the guns or the turret if he wasn’t careful. That was another thing they needed for their flying dog, Robert reflected ruefully—a flying harness, so they could strap him in properly.

Robert felt Capka begin his last turn, which would line the Wellington up with the runway itself—the maneuver known as “the final.” Right now it was

beyond final

—for they had zero fuel left in their tanks. To his left one of the engines began to cough and splutter as it sipped on fumes. Robert saw a faint red glow within the fog to his left, lighting it up an eerie pink. Moments later the squat form of a hangar roof loomed out of the fog, and as Robert gripped his dog in a crushing hold the ground rushed up to meet them.

There was a thump and a screech of tires hitting solid ground, and moments later the Wellington was thundering along the runway of RAF Honington. Capka held tight to the controls as the aircraft rolled to a halt, still on the runway and still intact. Their pilot had made a perfect landing with zero fuel, only one working engine, and next to zero visibility—he had been flying on instruments only.