The Dog that Dumped on my Doona (8 page)

Actually, I was praying she

would

fl ush. This time, she'd waited until I'd peed.

âI'm sorry,' I said. She was going to flush anyway. I thought a quick guilty plea would speed things up. I was wrong.

âFor what, Mucus,' she screamed. âYou're sorry for what?'

âFor everything,' I said. âFor being me.'

That wasn't the right answer. She pushed my head even closer to the water. The smell was starting to make my eyes sting. Once again, my resolve to keep my dignity under torture lasted less than a thousandth of a second.

âI'm sorry I was a loser at breakfast,' I burbled, âforcing you to make a loser sign at me, thus dropping Weet-Bix down yourself, causing you to jump and pebble-dash Dad's bald spot, and all because of me being a loser, which is absolutely not your fault.'

She flushed anyway.

I dried my hair and totted up the score for the week so far. Two dunkings, ripping me off for the iPod. I read somewhere that revenge is a dish best served cold. I didn't care if it was microwaved on high for two hours.

Rose was going to get hers.

I might be eccentric, but I'm not

always

harmless.

I couldn't believe my eyes.

The whole school, it seemed, was outside the gates. There were hundreds of kids milling around, as well as dozens of parents who'd come to drop their children off and stayed to find out what was happening. No one was going into the school. I could see teachers moving around the yard, surrounded by kids. Most were waving their arms around in a I-haven't-got-a-clue-what-is-going-on fashion. I joined the crowd.

âWassup?' I asked David, who just happened to be the first person I bumped into.

âSomething's going on,' he said, which wasn't exactly news. You didn't have to be a genius to work out that something was going on. The big question was what. âHey,' he continued. âOne hundred and seventy-five dollars.'

I groaned. The way things were going, he'd be offering me more for that iPod than he'd pay in a shop.

âDavid,' I said. âI wish you'd offered me a sensible price in the first place. I've sold it, mate. It's gone.'

âI was negotiating,' he replied. âYou should have been patient.'

I didn't want to think about it. It would make me too depressed. Then Miss Prentice, our Principal, appeared in the yard and I put everything else out of my mind.

She was carrying one of those electric things that magnify your voice and it was clear she wasn't afraid to use it.

âAttention, please,' she said, which was unnecessary since the volume was cranked up full. There were probably people thirty kilometres away who were raised from deep sleep to full attention. âI regret to inform you that school today is cancelled.'

She waited for the cheers to die down. This took some time. âThere is a problem with the electrics â a problem that is being worked on as we speak. But I have been told it is extremely unlikely the problem will be fixed before close of school today. Given that there is no power anywhere in the building I have no choice but to pass on the Director of Education's advice that school is closed. Would all students please report to a teacher so that we may ring home and explain the situation. Finally, I have been assured that we will be open tomorrow, so please attend as normal. Thank you.'

This was fantastic. This was just too good to be true.

It

was

too good to be true.

âDylan,' I whispered. âWhat have you done now?'

I only found him after the crowd had thinned out. He was moving among the kids, collecting money in a big tin. When I got close, he looked up, saw me and smiled.

âExplanation, please, Dyl,' I said.

âIn a few,' he replied. âI've still got some kids to see. Meet me in the park across the road.'

It didn't take long. Ten minutes, tops.

âExplanation, please, Dyl,' I said again.

âHey,' he said. âAll in good time. First, we've got to count this up.' He knelt and tipped the tin out onto the grass at my feet. Coins rolled everywhere. Quite a few were gold. I joined him on my knees. For once, Dylan was right. An explanation could wait. I wasn't even sure I wanted to hear it. I suspected it might cause me a sleepless night or two.

Anyway, I couldn't trust him to do the counting. Otherwise, the total would come out somewhere between one dollar and forty cents and four million. Whatever, you could guarantee it wouldn't be accurate. So I started to divide the coins into piles according to value, while Dylan poured yet another cola down his throat.

âSeventy-four dollars and fifty-five cents,' I said finally. âPlus an assortment of coins from Thailand, China and â interestingly â the Ivory Coast.'

âIf I find out who put them in,' said Dylan, âthere's gonna be trouble. Still, never mind, eh? Told you I'd get money for you. Is it enough?'

âDyl,' I replied. âWe needed sixty. We got seventy-four and a bit. Does that sound enough to you?'

He frowned in concentration, so I put him out of his misery.

âIt's more than enough, mate. But what I want to know is how you got it.'

âA collection, Marc. Payments from grateful students.'

I sighed.

âTell me, Dylan,' I said. âTell me how you destroyed the electrical system of an entire school and closed the place down.'

âAh,' he said, taking another can of cola from the pocket of his jacket. âThat wasn't so difficult. Simple destruction, really. I'm good at destruction. Everyone says so.'

I waited.

That's one thing about Dylan. He has no fear. None whatsoever.

While I was talking to God at the pet shop, Dylan had been hiding in a cupboard at school. It was dark and cramped in that cupboard. And boring when he'd been in it for an hour and a half, despite the fact he could hear Mr Bauer marking Maths test papers and cursing loudly at the stupidity of those who had written them. The novelty of hearing a teacher swear quickly wears off, according to Dylan.

Most people might have worried that Mr Bauer would open the cupboard in his classroom. To put something away or take something out. Most people might have worried about having to explain what you were doing there, crammed up against old exercise books and whiteboard cleaning products. But Dylan is not most people. He has no fear.

Eventually, Mr Bauer left and Dylan emerged, blinking, into a school that was pretty much deserted. Apart from the caretaker and assorted cleaning staff, that is.

It was Dylan's job to avoid them while making his way to the main electrical switchboard down in the basement. Dylan knew where it was. He'd spent many happy hours down there when he should have been in Remedial Maths, so the route was locked in his brain. Along with the promises he'd gathered that afternoon. Promises of money from kids who, for their various reasons, didn't want to go to school the following day.

He got to the basement without any problems, but the door to the switchboard was locked, so Dyl had to double back, nip into the caretaker's office, find the correct key hanging on the wall and retrace his steps. Not a problem for someone without fear. Eventually, he opened up the electrical mains box. Row after row of switches lay before him. And tangles of wires.

Dylan is not a whiz at Science. He is not a whiz at anything really, if you don't count window-smashing. But he had a certain fondness for electricity. Remember the scissors and the afro? And he knew that electrics and water don't mix. There wasn't any water down there in the basement. But Dylan had brought his own. After all, an hour and a half in a cupboard with nothing but five cans of cola to drink â¦

Apparently, the mains box provided a brilliant fireworks display. Sparks leapt everywhere. Electricity arced. I knew more about Science than Dylan. There are termites that have a better grasp of Science than Dylan. But I didn't like to point out to him that electricity can follow water back to its source.

That he was very, very lucky he wasn't the only person present at his own personal sausage sizzle.

And that was it. Apart from getting out of the building while a puzzled caretaker raced around trying to discover why all the lights had suddenly gone out. But that was easy.

Dylan doesn't have any fear.

âLet's go and buy God,' he said.

I couldn't think of one reason why not.

The guy with the upside-down head was back. I was relieved.

Me and Dylan had whipped back to my place to collect the rest of the money and then gone straight to the shop. I'd whistled for Blacky, but he hadn't shown. Probably just as well. He wouldn't have liked being whistled. Typical, I thought. He was always hanging round like a bad smell â normally

with

a bad smell â but when you wanted him he was nowhere to be seen.

Dylan carried the tin. I kept the other two hundred tucked tightly down into my pants pocket.

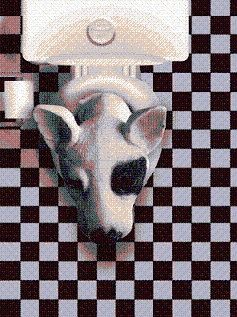

âI'd like to buy the pygmy bearded dragon, please,' I said.

âNo worries,' said the Beard. âYou've got a reptile licence, I take it?'

My jaw hit the floor.

âSorry?'

âA reptile licence. You need one from Parks and Wildlife to keep a reptile.'

My tongue seemed to have become stuck to the roof of my mouth. I shook my head.

âNo worries,' repeated the Beard. âWe can fax off an application form. You're thirteen years old, right?'

I shook my head again.

âWorries,' said the Beard. âBut not impossible. What you need to do, kid, is bring a parent in to sign the form. No worries then. The bearded dragon is yours.'

I walked out of the shop in a daze. So close and yet so far. I couldn't quite believe it.

âYou should have said you were thirteen,' said Dylan. âHe wouldn't have known any different.'

He was right. I knew he was right. But I wasn't thinking straight. It's really annoying the way truth just seems to pop out at the worst possible moment. And now I had another barrier to get over. My parents? Signing a form to say I could keep a reptile? About as likely as Rose returning my iPod and sticking her own head down the toilet.

âHow about I find a brick?' said Dylan.

I ducked into the shop again.

âI'll be right back,' I said. âDon't sell him, will you?'

âNo worries,' said the Beard.

Not for you, maybe

, I thought.

âI'm glad you asked me,' said Rose. âTo be honest, I've been feeling bad about the way I treated you. Ripping you off for the iPod, sticking your head down the toilet for no good reason and generally being a horse's rear end. I would be honoured to go to the pet shop with you and sign the necessary forms.'

It didn't happen like that.

Rose got home from her school and I tackled her straightaway.

âHelp you buy a lizard?' she said. Her mouth was all puckered up like a bumhole. âA disgusting, slimy lizard? Mucus, you are a sad loser. What's more, you're clearly insane if you think I would lift a finger to help you do anything, let alone buy something revolting like that.'

âI won't be keeping him.'

âThat's because you're not buying him in the first place.

Hello

?'

âRose, please â¦'