The Dirt (4 page)

Authors: Tommy Lee

Mexico was probably the best time of my childhood: I ran around naked with the Mexican kids on the beach near our cottage, played with the goats and chickens roaming the neighborhood like they owned it, ate ceviche, went into town for fire-cooked corn ears wrapped in tinfoil, and, at the age of seven, smoked pot for the first time with my mother.

When Mexico grew stale for them, we returned to Idaho, where my grandparents bought me my first phonograph, a gray plastic toy that only played singles. It had a needle on the lid, so whenever it was closed the song played and when it was open it stopped. I used to listen to Alvin and the Chipmunks all the time, which my mother never let me forget.

A year later, we all piled into a U-Haul trailer and headed for El Paso, Texas. My grandfather slept in a sleeping bag outside, my grandmother napped in a seat, and I curled up on the floor like a dog. At the age of eight, I was already sick of touring.

After so much traveling, spending most of my time in the company of myself, friendship became like television to me: It was something to flip on now and then to distract myself from the fact that I was alone. Whenever I was around a group of kids my age, I felt awkward and out of place. In school, I had trouble focusing. It was hard to care or pay attention when I knew that before the year was up, I’d be gone and never have to see any of those teachers or kids again.

In El Paso, my grandfather worked at a Shell gas station, my grandmother stayed in the trailer, and I went to the local grade school, where the kids were merciless. They pushed me, picked on me, and said I ran like a girl. Every day as I walked alone to school, I’d have to cross the high school yard and get pelted with soccer balls, footballs, and food. To further my humiliation, my grandfather cut my hair, which my mother had always let grow long, into a flattop—not the most popular style in the late sixties.

I eventually grew to like El Paso because I started spending time with Victor, a hyperactive Mexican kid who lived across the street. We became best friends and did everything together, enabling me to ignore the scores of other kids who hated my guts because I was poor white California trash. But just as I began to get comfortable, the inevitable news came: We were moving again. I was devastated, because this time I would have to leave someone behind, Victor.

WE MOVED TO THE MIDDLE OF THE DESERT in Anthony, New Mexico, because my grandparents thought they could make more money on a hog farm. We raised chickens and rabbits as well as pigs. My job was to take each rabbit, hold him by his hind legs, grab a stick, and smash it into the fur on the back of his head. His body would convulse in my hands, blood would drip out of his nose, and I’d stand there thinking, “He was just my friend. I’m killing my friends.” But at the same time I knew that slaughtering them was my role in the family; it was what I had to do to become a man.

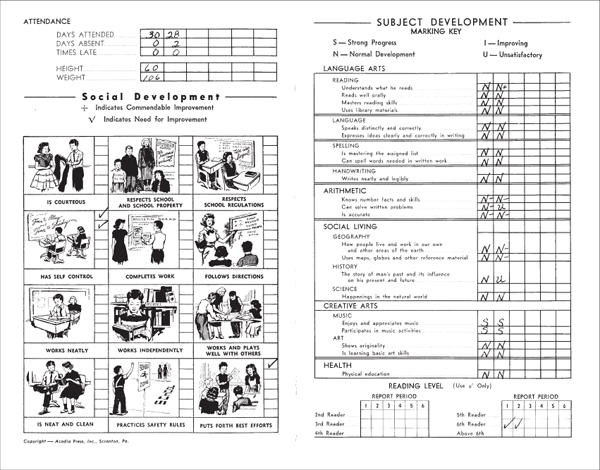

fig. 4

Nikki’s sixth grade report card, Anthony, New Mexico, Gasden School District

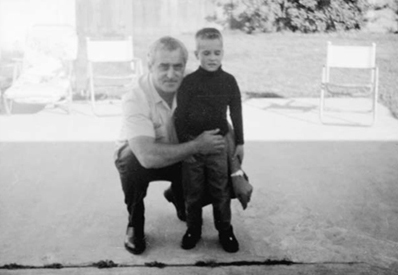

fig. 5

Nikki’s father, Frank Feranna

School was a ninety-minute bus ride of unpaved roads and constant bullying away. When we arrived, the older kids who sat in the back of the bus would push me to the ground and stand on me until I gave them my lunch money. After the first seven times, I vowed that it would never happen again. The next day, it happened again.

The following morning, I brought a metal

Apollo 13

lunch box with me and filled it with rocks at the bus stop. As soon as we arrived at school, I ran off the bus and, as usual, they caught up with me. But this time, I started swinging, breaking noses, denting heads, and sending blood everywhere until the lunch box broke open on connecting with the face of one inbred shitkicker.

They never fucked with me again—and I felt power. Instead of cowering around older kids, I’d just think, “Don’t start with me, because I will fuck you up.” And I did: If anyone pushed me, I’d fucking deck them. I was demented, and they all started to realize that and kept their distance. Instead of skipping stones when I was alone, I started walking down dirt roads with my BB gun, picking off all things animate and inanimate. My only friend was an old lady who lived in a trailer nearby, all alone in the middle of the desert. She’d sit on her faded flower-patterned couch and drink vodka while I fed the goldfish.

After a year of living in Anthony, my grandparents decided that raising pigs wasn’t the road to riches they had thought it would be. When they told me we’d be moving back to El Paso—one block from our old house—I was ecstatic. I would get to see my friend Victor again.

But I wasn’t the same me anymore—I was bitter and destructive—and Victor had found new friends. I passed by his house at least twice a day, feeling my isolation and anger grow, before walking through the high school to get pelted with sports equipment on the way to the Gasden District Junior High that I hated. I started stealing books and clothes from people’s lockers out of spite and going into the general store, Piggly Wiggly’s, and swiping candy and sticking Hot Wheels in the ten-cent bags of popcorn hoping people would choke on them. For Christmas, my grandfather sold some of his most prized possessions—including his radio and his only suit—just to buy me a buck knife, and I rewarded his sacrifice by using it to slash tires. Revenge, self-hate, and boredom had opened up the path to juvenile delinquency for me. And I chose to follow it to the very end.

My grandparents eventually moved back to Idaho, to a sixty-acre cornfield in Twin Falls. We lived next to a silage pit, which is where the extra husks and waste left over after harvesting were dumped, mixed with chemicals, covered with plastic, and left to rot in the ground until they stank enough to feed to the cows. I lived a Huckleberry Finn life that summer—fishing in the creek, walking along the railroad tracks, crushing pennies under trains, and building forts out of haystacks.

Most evenings, I would run around the house, pretending like I had a motorcycle, then lock myself in my room and listen to the radio. One night, the DJ played “Big Bad John,” by Jimmy Dean, and I lost my mind. It cut through the boredom like a scythe. The song had style and attitude: It was cool. “I found it,” I thought. “This is what I’ve been looking for.” I phoned the station so much to request “Big Bad John” that the DJ told me to stop calling.

When school started, it was like Anthony all over again. The kids picked on me and I had to resort to my fists to stop them. They made fun of my hair, my face, my shoes, my clothes—nothing about me fit. I felt like a puzzle with a piece missing, and I couldn’t figure out what that piece was or where I could find it. So I joined the football team because violence was the only thing that gave me any sense of power over other people. I made the first string and, though I played both offense and defense, I thrived as a defensive end where I could just cream the quarterbacks. I loved hurting those motherfuckers. I was psycho. I’d get so worked up on the field I’d whip my helmet off and start smashing other kids with it, just like it was my

Apollo 13

lunch box in Anthony. My grandfather still tells me, “You play rock and roll exactly like you played football.”

Through football came respect, and through football and respect came girls. They started noticing me and I started noticing them. But just when I was finally starting to find a niche, my grandparents moved—to Jerome, Idaho—and I had to start all over again. But this time, there was a difference: thanks to Jimmy Dean, I had music. I’d listen to the radio ten hours a day: Deep Purple, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Pink Floyd. However, the first record that I bought was

Nilsson Schmilsson

, by Harry Nilsson. I had no choice.

One of my first friends, a redneck named Pete, had a sister who was a tan, blond small-town hottie. She’d walk around in short cutoff jeans that sent me into convulsions of desire and panic. Her legs were golden arches, and every night in bed all I could think about was how well I would fit between them. I’d follow her around like a clown, tripping over my own shoes. She hung out at a combination pharmacy, soda shop, and record store where, when I finally saved up enough money to buy Deep Purple’s

Fireball

, she smiled at me with those big white teeth and suddenly I found myself buying

Nilsson Schmilsson

because she had mentioned it.