The Dictator

Also by Robert Harris

FICTION

Conspirata

The Ghost Writer

Imperium

Pompeii

Archangel

Enigma

Fatherland

The Fear Index

An Officer and a Spy

NONFICTION

Selling Hitler

A Higher Form of Killing

(with Jeremy Paxman)

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright © 2015 by Robert Harris

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Hutchinson, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, in 2015.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

ISBN 9780307957948 (hardcover) /ISBN 9780307957962 (eBook)

LCCN: 2015955103

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

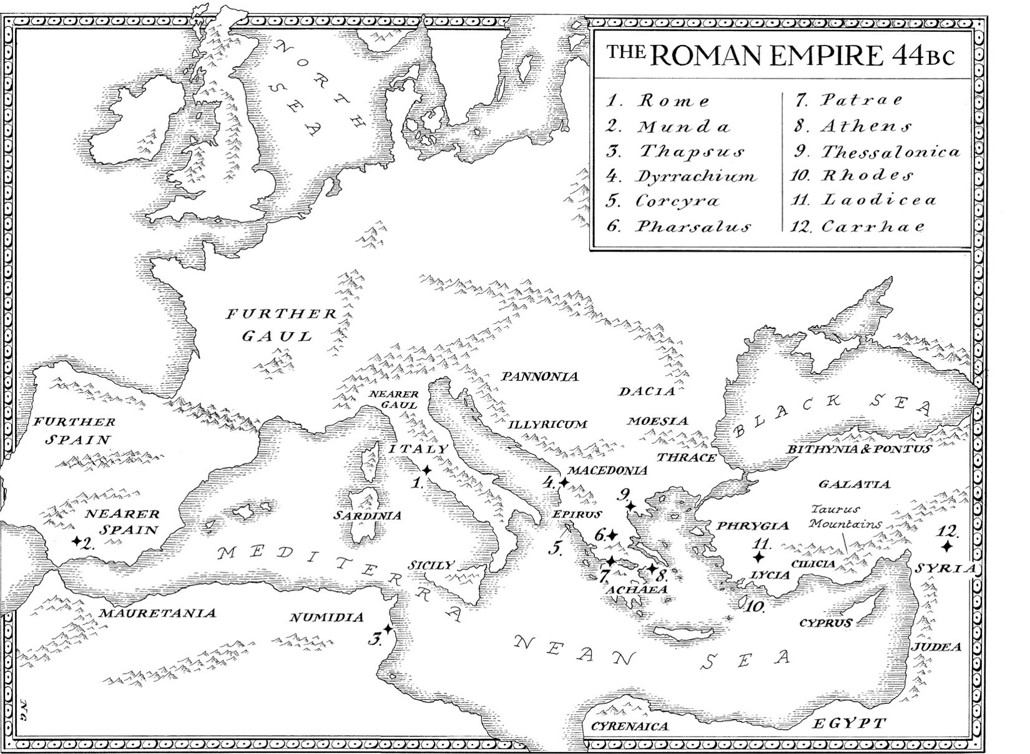

Maps by Neil Gower

Cover illustration by Matt Buck

v4.1

ep

To Holly

The melancholy of the antique world seems to me more profound than that of the moderns, all of whom more or less imply that beyond the dark void lies immortality. But for the ancients that “black hole” was infinity itself; their dreams loom and vanish against a background of immutable ebony. No crying out, no convulsions—nothing but the fixity of a pensive gaze. Just when the gods had ceased to be and the Christ had not yet come, there was a unique moment in history, between Cicero and Marcus Aurelius, when man stood alone. Nowhere else do I find that particular grandeur.

—Gustave Flaubert, letter to Mme Roger de Genettes, 1861

Alive, Cicero enhanced life. So can his letters do, if only for a student here and there, taking time away from belittling despairs to live among Virgil’s Togaed People, desperate masters of a larger world.

—D. R. Shackleton Bailey,

Cicero

,1971

Contents

Detail left

Detail right

Dictator

tells the story of the final fifteen years in the life of the Roman statesman Cicero, imagined in the form of a biography written by his secretary, Tiro.

That there was such a man as Tiro and that he wrote such a book are well-attested historical facts. Born a slave on the family estate, he was three years younger than his master but long outlived him, surviving, according to Saint Jerome, until he reached his hundredth year.

“Your services to me are beyond count,” Cicero wrote to him in 50

BC

, “in my home and out of it, in Rome and abroad, in private affairs and public, in my studies and literary work…” Tiro was the first man to record a speech in the Senate verbatim, and his shorthand system, known as

Notae Tironianae,

was still in use in the Church in the sixth century; indeed some traces of it (the symbol “&,” the abbreviations etc., NB, i.e., e.g.) survive to this day. He also wrote several treatises on the development of Latin. His multi-volume life of Cicero is referred to as a source by the first-century historian Asconius Pedianus; Plutarch cites it twice. But, like the rest of Tiro’s literary output, the book disappeared amid the collapse of the Roman Empire.

What must it have been like, one wonders? Cicero’s life was extraordinary, even by the hectic standards of the age. From relatively lowly origins compared to his aristocratic rivals, and despite his lack of interest in military matters, deploying his skill as an orator and the brilliance of his intellect he rose at meteoric speed through the Roman political system, until, against all the odds, he finally was elected consul at the youngest-permitted age of forty-two.

There followed a crisis-stricken year in office—63

BC

—during which he was obliged to deal with a conspiracy to overthrow the republic led by Sergius Catilina. To suppress the revolt, the Senate, under Cicero’s presidency, ordered the execution of five prominent citizens—an episode that haunted his career ever afterwards.

When subsequently the three most powerful men in Rome—Julius Caesar, Pompey the Great and Marcus Crassus—joined forces in a so-called triumvirate to dominate the state, Cicero decided to oppose them. Caesar in retaliation, using his powers as chief priest, unleashed the ambitious aristocratic demagogue, Clodius—an old enemy of Cicero’s—to destroy him. By allowing Clodius to renounce his patrician status and become a plebeian, Caesar opened the way for his election as tribune. Tribunes had the power to haul citizens before the people, to harass and persecute them. Cicero swiftly decided he had no choice but to flee Rome. It is at this desperate point in his fortunes that

Dictator

begins.

My aim has been to describe, as accurately as I can within the conventions of fiction, the end of the Roman Republic as it might have been experienced by Cicero and Tiro. Wherever possible, the letters and speeches and descriptions of events have been drawn from the original sources.