The Devils of Loudun (35 page)

Partly in shame—for he remembered those Latin lessons and his abandonment of the desperately weeping girl—and partly out of a fear lest the spectacle of their triumph might move him to bitterness and make him forget that God was even here, even now, Grandier dropped his eyes.

A hand touched him on the shoulder. It was La Grange, the captain of the guard, who had come to ask the parson’s forgiveness for what he had been obliged to do. Then he made two promises: the prisoner would be allowed to make a speech and, before the fire was lighted, he would be strangled. Grandier thanked him, and La Grange turned away to give his orders to the executioner, who immediately prepared a noose.

Meanwhile the friars were busy with their exorcisms.

“Ecce crucem Domini, fugite partes adversae, vicit leo de tribu Juda, radix David. Exorciso te, creatura ligni, in nomine Dei patris omnipotentis, et in nomine Jesus Christi filii ejus Domini nostri, et in virtute Spiritus sancti. . . .”

1

1

They sprinkled the wood, the straw, the glowing coals of the brazier that stood ready beside the pyre; they sprinkled the earth, the air, the victim, the executioners, the spectators. This time, they swore, no devil should prevent the wretch from suffering to the extreme limit of his capacity for pain. Several times the parson tried to address the crowd; but no sooner had he begun than they threw holy water in his face or hit him on the mouth with an iron crucifix. When he flinched from the blow, the friars would shout triumphantly that the renegade was denying his Redeemer. And all the time Father Lactance kept calling on the prisoner to confess.

“

Dicas!

” he shouted.

Dicas!

” he shouted.

The word caught the fancy of the onlookers and for the brief and horrible remainder of his life the Recollet was always known in Loudun as Father Dicas.

“Dicas! Dicas!”

For the thousandth time Grandier answered that he had nothing to confess.

“And now,” he added, “give me the kiss of peace and let me die.”

At first Lactance refused; but when the crowd protested against such an un-Christian malignity, he climbed on to the pile of faggots and kissed the parson’s cheek.

“Judas!” cried a voice, and a score of others took up the refrain.

“Judas, Judas. . . .”

Lactance heard them and, in a passion of uncontrollable rage, jumped down from the pyre, seized a twist of straw and, lighting it in the brazier, waved the flame in the victim’s face. Let him confess who he was—the devil’s servant! Let him confess, let him renounce his master!

“Father,” said Grandier with a calm and gentle dignity that contrasted strangely with the almost hysterical malice of his accusers, “I am about to meet the God who is my witness that I have spoken the truth.”

“Confess,” the friar fairly screamed. “Confess! . . . You have only a moment to live.”

“Only a moment,” the parson repeated slowly. “Only a moment—and then I go to that just and fearful judgment to which, Reverend Father, you too must soon be called.”

Without waiting to hear anything more, Father Lactance threw his torch on to the straw of the pyre. Hardly visible in the bright afternoon sunshine, a little flame appeared and began to creep, growing larger as it advanced, towards the bundles of dry kindling. Following the Recollet’s example, Father Archangel set fire to the straw on the opposite side of the pyre. A thin blue haze of smoke rose into the windless air. Then, with a cheerful crackling, like the noise that accompanies the drinking of mulled wine on a winter evening by the hearth, one of the faggots caught fire.

The prisoner heard the sound and, turning his head, saw the gay dancing of flames.

“Is this what you promised me?” he called to La Grange in a tone of agonized protest.

And suddenly the divine presence was eclipsed. There was no God, no Christ, nothing but fear.

La Grange shouted indignantly at the friars and tried to extinguish the nearest flames. But there were too many of them to be stamped out; and here was Father Tranquille setting fire to the straw behind the parson’s back, here was Father Lactance lighting another torch at the brazier.

“Strangle him,” he ordered. And the crowd took up the cry. “Strangle, strangle!”

The executioner ran for his noose, only to discover that one of the Capuchins had surreptitiously knotted the rope so that it could not be used. By the time the knots were undone, it was too late. Between the executioner and the victim he had intended to save from this last agony there was a wall of flame, a billowing curtain of smoke. Meanwhile, with whisk and holy water pot, the friars were ridding the bonfire of its remaining devils.

“Exorciso te, creatura ignis. . . .”

The water hissed among the burning logs and was turned in an instant to steam. From the further side of the wall of flames came a sound of screaming. The exorcism, it was evident, had begun to take effect. The friars paused for a moment to give thanks; then, with faith renewed and energy redoubled, they set to work again.

“Draco nequissime, serpens antique, immundissime spiritus . . .”

At this moment a large black fly appeared from nowhere, bumped into Father Lactance’s face and dropped on the opened pages of his book of exorcism. A fly—and as large as a walnut! And Beelzebub was the Lord of Flies!

“

Imperat tibi Martyrum sanguis

,” he shouted above the roaring of the fire, “

Imperat tibi continentia Confessorum

. . .”

Imperat tibi Martyrum sanguis

,” he shouted above the roaring of the fire, “

Imperat tibi continentia Confessorum

. . .”

With a preternaturally loud buzz the insect took wing and disappeared into the smoke.

“In nomine Agni, qui ambulavit super aspidem et basiliscum. . . .”

All at once the screams were strangled by a paroxysm of coughing. The wretch was trying to cheat them by dying of suffocation! To frustrate this latest of Satan’s wiles, Lactance hurled a whiskful of holy water into the smoke.

“Exorciso te, creatura fumi. Effugiat atque discedat a te nequitia omnis ac versutia diabolicae fraudis. . . .”

It worked! The coughing stopped. There was another cry, then silence. And suddenly, to the consternation of the Recollet and his Capuchin colleagues, the blackened thing at the centre of the bonfire began to speak.

“

Deus meus

,” it said, “

miserere mei Deus

.” And then, in French, “Forgive them, forgive my enemies.”

Deus meus

,” it said, “

miserere mei Deus

.” And then, in French, “Forgive them, forgive my enemies.”

The coughing began again. A moment later the cords which bound him to the post gave way and the victim tumbled sideways among the blazing logs.

The fire burned on, the good fathers continued to sprinkle and intone. Suddenly a flock of pigeons came swooping down from the church and started to wheel around the roaring column of flame and smoke. The crowd shouted, the archers waved their halberds at the birds, Lactance and Tranquille splashed them on the wing with holy water. In vain. The pigeons were not to be driven away. Round and round they flew, diving through the smoke, singeing their feathers in the flames. Both parties claimed a miracle. For the parson’s enemies the birds, quite obviously, were a troop of devils, come to fetch away his soul. For his friends, they were emblems of the Holy Ghost and living proof of his innocence. It never seems to have occurred to anyone that they were just pigeons, obeying the laws of their own, their blessedly other-than-human nature.

When the fire had burned itself out, the executioner scattered four shovelfuls of ashes, one towards each of the cardinal points of the compass. Then the crowd surged forward. Burning their fingers, men and women rummaged in the hot flaky dust, hunting for teeth, for fragments of the skull and pelvis, for any cinder showing the black smear of burned flesh. A few, no doubt, were merely souvenir hunters; but most of them were in search of relics, for a charm to bring luck or compel reluctant love, for a talisman against headaches or constipation or the malice of enemies. And these charred

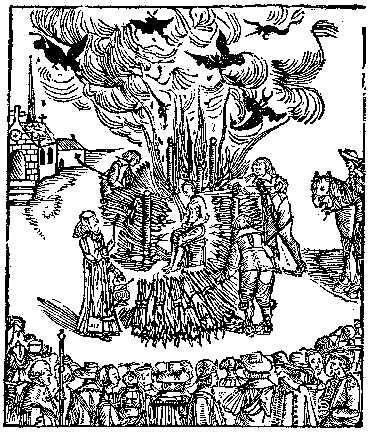

THE BURNING OF GRANDIER, 1634

An engraving from

Urbain Grandier et les Possédées de Loudun

by Dr. Gabriel Legué

Urbain Grandier et les Possédées de Loudun

by Dr. Gabriel Legué

odds and ends would be no less effective if the parson were guilty of the crimes imputed to him, than if he were innocent. The power to work miracles lies, not in the source of a relic, but in its reputation, however acquired. Constant throughout history, a certain percentage of human beings can be restored to health or happiness by practically anything that has been well advertised—from Lourdes to witchcraft, from the Ganges to patent medicines and Mrs. Eddy, from the thaumaturgical arm of St. Francis Xavier to those “pigges bones” which Chaucer’s Pardoner carried in a glass for all to see and worship. If Grandier were what the Capuchins had said he was, that was excellent: even in ashes, a sorcerer is richly charged with power. And his relics would be charged with no less power if the parson were guiltless; for in that case he would be a martyr, equal to the best of them. In a little while most of the ashes had disappeared. Horribly tired and thirsty, but happy in the thought that their pockets were bulging with relics, tourists and townsfolk drifted away in search of a drink and the chance to take off their shoes.

That evening, after only the briefest of rests and the lightest of refreshments, the good fathers re-assembled at the Ursuline convent. The Prioress was exorcized, duly went into convulsions, and in response to Lactance’s questioning announced that the black fly was none other than Baruch, the parson’s familiar. And why had Baruch hurled himself so rudely on the book of exorcisms? S

œ

ur Jeanne bent herself backwards until her head touched her heels, then did the splits and finally answered that he had been trying to throw the book into the fire. It was all so edifying that the friars decided to break off for the night and begin again next morning, in public.

œ

ur Jeanne bent herself backwards until her head touched her heels, then did the splits and finally answered that he had been trying to throw the book into the fire. It was all so edifying that the friars decided to break off for the night and begin again next morning, in public.

On the following day the sisters were taken to Sainte-Croix. Many of the tourists were still in town, and the church was crowded to the doors. The Prioress was exorcized and, after the usual preliminaries, identified herself as Isacaaron, the only devil presently at home; for all the other tenants of her body had gone back to hell for the wild party which had been organized for the reception of Grandier’s soul.

Judiciously questioned, S

œ

ur Jeanne confirmed what the exorcists had been saying all along—namely, that when Grandier had said ‘God’ he always meant ‘Satan,’ and that when he had renounced the devil he had actually been renouncing Christ.

œ

ur Jeanne confirmed what the exorcists had been saying all along—namely, that when Grandier had said ‘God’ he always meant ‘Satan,’ and that when he had renounced the devil he had actually been renouncing Christ.

Lactance then wanted to know what kind of torments the parson was suffering down there, and was evidently rather disappointed when the Prioress told him that the worst of them was the privation of God.

No doubt, no doubt. But what were the

physical

tortures?

physical

tortures?

After a good deal of pressing Sœur Jeanne replied that Grandier “had a special torture for each of the sins he had committed, especially those of the flesh.”

And what about the execution? Had the devil been able to prevent the wretch from suffering?

Alas, replied Isacaaron, Satan had been frustrated by the exorcisms. If the fire had not been blessed, the parson would have felt nothing. But thanks to the labours of Lactance, Tranquille and Archangel he had suffered excruciatingly.

But not so excruciatingly, cried the exorcist, as he was suffering now! And with a kind of gloating horror, Father Lactance brought the conversation back to hell. In which of hell’s many mansions was the magician lodged? How had Lucifer received him? What precisely was being done to him at this moment? Sister Jane’s Isacaaron did his best to answer. Then, when his imagination began to flag, Sister Agnes was thrown into fits, and Beherit was invited to say his piece.

That evening, at the convent, the friars noticed that Father Lactance looked pale and seemed strangely preoccupied. Was he feeling ill?

Father Lactance shook his head. No, he was not ill. But the prisoner had asked to see Father Grillau, and they had denied him. Could it be that they had committed a sin by making it impossible for him to confess?

His colleagues did their best to reassure him, but without success. Next morning, after a sleepless night, Lactance was in a fever.

“God is punishing me,” he kept repeating, “God is punishing me.”

Other books

Tribute for the Viking (reluctant gay erotica) by Calandra Hunter

Problems with People by David Guterson

Next World Novella by Politycki, Matthias

Werewolves in Love 1.5: The Nanny Years by Kinsey Holley

The Year’s Best Military SF & Space Opera by David Afsharirad

The Last Hunter - Collected Edition by Jeremy Robinson

Dead Men Scare Me Stupid by John Swartzwelder

Necrophenia by Robert Rankin

Bad Things by Tamara Thorne

A Beautiful Place to Die by Philip Craig