The Delaware Canal (20 page)

Read The Delaware Canal Online

Authors: Marie Murphy Duess

John Fulton Folinsbee,

Lock, New Hope. Courtesy of Gratz Gallery, New Hope, PA

.

It is easy to understand why artists and early photographers were so attracted to the Delaware Division Canal.

Courtesy of Historic Langhorne Association

.

Most of these artists lived beyond the end of the canal age, long after the Delaware Canal had ceased to be an avenue of commerce. They witnessed the once busy canal become empty, one boat after another disappearing from the water, its rough and ready captains and the young mule drivers in bare feet passing their studios less and less frequently. The sound of the tinkling bells and padded hoofbeats of the mules faded. Yet most of the artists remained living and working on the now quiet and peaceful canalâperhaps they liked it even better in its serenity.

Artists are still drawn to the canal's beauty. In a 2007 summer boat excursion on the Delaware Canal with the New Hope Canal Boat Company, two artists were seen sittingâone on the towpath and one on the bermâtheir canvasses in front of them, their paint-stained palettes beside them, as they immortalized the present canal just as Redfield, Schofield, Lathrop, Coppedge, Folinsbee and Wagner had during the previous century.

Chapter 12

National Historic Landmark

The seminal role of the canals in the ferment of the Industrial Revolution is little appreciated today. Yet it can be traced directly to Josiah White and Erskine Hazard, owners of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, and their quest for expanding markets for their coalâ¦The decline of the canals started with the building of the railroads and continued with the adoption of coke as the primary fuel for smelting iron. As more rail lines were builtâ¦less traffic went by the canal

.

âAnn Bartholomew and Lance Metz

, Delaware and Lehigh Canals

Demise of the Canals

During the years that the Pennsylvania canals enjoyed moderate success as a major transportation mode for moving coal, lumber and other goods, the railroads were being established as well. New immigrants arriving in America were being put to work laying the rails in all directions, while better and bigger steam engines were built.

After the Civil War, the country experienced a wave of prosperity, followed by a severe economic panic in 1873 that affected the entire nation. As a result of government-promoted speculative credit, there was a huge overexpansion of the nation's railroad network. The Coinage Act of 1873 created a depreciation of silver. A chain of bank failures caused the stock market to close for ten days. Numerous railroads went bankrupt, and businesses failed. It was also the beginning of the decline of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company.

In 1866, at the height of the canal era, 792,000 tons of coal were pulled upon the canal annually. In 1915, that amount dropped to 130,000 tons, and in 1931, only 65,000 tons moved from Easton to Bristol.

70

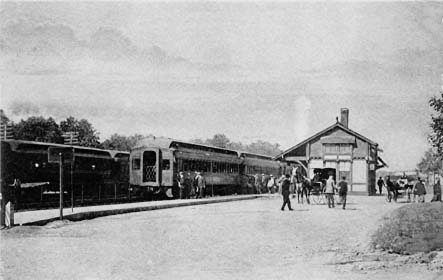

With the arrival of the freight trains, the American canals began to decline.

Railroads took over as the most efficient means of transporting anthracite coal and other cargo in the mid- to late nineteenth century, and the once busy canals became obsolete.

Courtesy of the Historic Langhorne Association

.

Additionally, roadways were being improved, and the automobile was taking over as the most expedient and popular means of transportation, followed by the sturdier truck. Use of canals in other parts of the country was decreasing rapidly in the late part of the nineteenth century. Coal was still the predominant fuel for homes and industry in the early part of the twentieth century, but now the coal companies were using rail and automotive means to transport it to even the smallest towns and villages, and trucks brought the coal right up to the houses, mills and factories.

The only reason the Delaware Canal lasted as long as it did was due to the fact that Delaware Canal coal yards still needed deliveries, and unlike most of the other canals in the country that stopped operations in the late 1800s, there was no parallel railroad from Easton to Bristol along the Delaware Division. It wasn't until the autumn of 1931 that the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company ended all commercial navigation on the canal when the costs of the operation couldn't be supported by the diminishing revenue.

Delaware State Park and Landmark Designation

The canal was left to the leisure boaters and Sunday picnics that had always been popular along the picturesque and now peaceful Delaware Canal. Nature took over as the company's nurturing of the canal declined, and it fell into disrepair, especially after floods and freshets. Residents along the canal who believed in the importance of its history and who loved its beauty worried that it would be lost forever and that the LC&N would give it to the state to pave over and make into a roadway. Committed individuals formed a group called the Delaware Valley Protective Association and lobbied the LC&N to deed the land and the canal to the commonwealth as a gift to the people of Pennsylvania. They succeeded, and on the very same day that the last empty canalboat made its return trip from Bristol to Easton, the LC&N deeded forty miles of the canal to Pennsylvania.

The ceremonial transfer took place on October 18, 1931, on the grounds of the Thompson-Neely Mill, a segment of Washington Crossing Historic Park. Governor Gifford Pinchot accepted the deed from William Jay Turner, general counsel for the LC&N. Numerous dignitaries attended, joined by preservation, historical, nature and artistic groups. In his speech, Governor Pinchot declared that all the bridges that crossed the canal would be preserved to “continue to help make the historic canal one of the beauty spots in the United States.”

71

Ceremonies marking the transfer of most of the Delaware Division Canal lands from the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company to the State of Pennsylvania took place on the historic Thompson-Neeley farm, which is now part of the Washington Crossing Historic Park.

Author's collection

.

The canal runs through the Thompson-Neely farm and past the cemetery, where soldiers of the Continental army were buried in unmarked graves during the Revolutionary War.

Author's collection

.

He named the stretch of park the Roosevelt State Park in honor of fellow preservationist and close friend Teddy Roosevelt. To confirm this sentiment on the part of the LC&N, William Turner said that the company had deeded the canal, the towpath and the berm along the canal “to assure perpetuity of the beautiful landscape we have all enjoyed these many years.”

72

The LC&N would remain in control of the canals above Easton and would in fact continue to provide the water for the Delaware Division from the slack water of the Lehigh River at Easton.

There were very interesting plans surrounding the formation of the park. The plans called for three major centers in the park, four minor centers and five special centers, and all would provide canoe and boat concessions. There would be dance boats, repair boats and cabin boats so that families could spend vacations on the canal. Jobs would be created with these concessions, and the state would hire supervisors, foremen, laborers, carpenters and other employees to staff facilities and operate the locks. None of these wonderful plans came to fruition. Once again, floods and freshets took their toll and the park had all it could do to keep the canal from falling in upon itself.

By 1936, no one wanted to take responsibility for the canal's repairs. James F. Bogardus, who was the deputy secretary of forests and waters, announced that the granting of a portion of the canal was unconstitutional. He claimed that this explained why the state wasn't responsible for repairing the aqueduct at Point Pleasant that had been badly damaged by a floodâthe LC&N still owned it and was responsible for its repair. The LC&N refused to assume responsibility, although the company did make minor repairs. The arguments and litigation went on until 1940, while residents along the canal where the water was stagnant complained of mosquitoes, unsightly weeds and general dismay about what was supposed to be an active waterway.

In 1947, the state finally appropriated $200,000 toward work on the canal, starting with the Point Pleasant aqueduct. Water would fill the canal again. However, the Durham aqueduct collapsed. It was repaired by 1951, but in 1955 the entire Delaware Valley was devastated by floods brought on by Hurricane Diane, and repairs on the canal would cost as much as $300,000.

The Delaware Canal as it is today in front of Chez Odette's, both of which suffered major damage during recent floods.

Author's collection

.

The canal was never to be completely filled with water again. Standing water that was present in sections wasn't suitable for swimming, and in many places the water wasn't high enough for boating of any sort. There were additional hazards such as fallen trees, cave-ins and litterâpicnic tables, chairs, pieces of cars, shopping carts. A small section of the canal was covered over with a parking lot.

Yet efforts on behalf of the beautiful historic waterway never ended. In 1974, in response to an application prepared by C.P. Yoder, then the curator of the National Canal Museum in Easton, the canal was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Due to further efforts made by Bucks County residents like Virginia Forrest and the Swope brothers, who had been canallers since childhood, the canal was dedicated a National Historic Landmark and the towpath a National Recreation Trail in 1978. The length of the canal was renamed the Delaware Canal State Park.