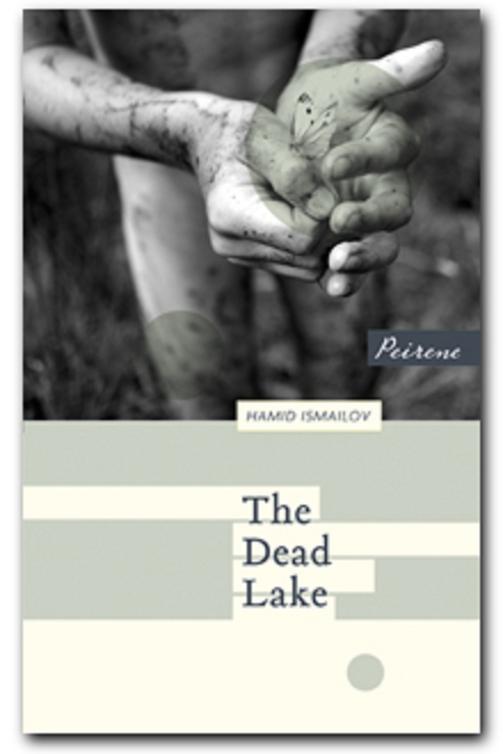

The Dead Lake

Authors: Hamid Ismailov

MEIKE ZIERVOGEL

PEIRENE PRESS

Like a Grimms’ fairy tale, this story transforms an innermost fear into an outward reality. We witness a prepubescent boy’s secret terror of not growing up into a man. We wander in a beautiful, fierce landscape like no other in Western literature. And by the end of Yerzhan’s tale we are awestruck by our human resilience in the face of catastrophic, man-made, follies.

Between 1949 and 1989 at the Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site (SNTS) a total of 468 nuclear explosions were carried out, comprising 125 atmospheric and 343 underground blasts. The aggregate yield of the nuclear devices tested in the atmosphere and underground at the SNTS (in a populated region) exceeded by a factor of 2,500 the power of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima by the Americans in 1945.

This story began in the most prosaic fashion possible. I was travelling across the boundless steppes of Kazakhstan on a train. The journey had already taken four nights. Trackmen at remote way stations tapped on the wheels with their hammers, swearing in Kazakh. I felt myself swell with a secret pride that I could understand them. During the day the platforms and corridors of the

carriages

were awash with women’s and children’s versions of the same tongue. At every way station the train was boarded by ever more vendors – all women – peddling camel wool, sun-dried fish or simply pellets of dried sour milk.

Of course, that was a long time ago. Perhaps nowadays things have changed. Although somehow I doubt it.

Anyway, I was standing at one end of the carriage, gazing out – for the fourth day already – at the dreary, monotonous steppe, when a ten- or twelve-year-old boy appeared at the other end. He held a violin and

suddenly

started playing with such incredible dexterity and panache that at once all the compartment doors slid open and passengers’ drowsy faces appeared. What they

heard wasn’t some flamboyant Gypsy refrain, or even a distinctive local melody; no, the boy played Brahms, one of the famous

Hungarian Dances

. He played as he walked, coming towards me. Then, just as he had the entire carriage gaping after him open-mouthed, he broke off in mid-note. He slung the violin back over his shoulder like a rifle. ‘Wholesome local beverage – entirely organic!’ he exclaimed in a thick, adult voice. He swung a canvas sack down off his other shoulder and pulled out an immense plastic bottle of a yoghurt drink, either

ayran

or

kumis

. I approached him, without even knowing why.

‘Young lad,’ I said, ‘how much is your

kumis

?’

‘In the first place, it’s not my

kumis

but the mare’s, and in the second place, it’s not

kumis

but

ayran

, and finally, I’m not a young lad!’ the urchin replied defiantly in perfect Russian.

‘You’re not a little girl though, are you?’ I clumsily attempted to smooth things over.

‘I’m not a woman, I’m a man! Like to try me? Drop your breeches!’ the youngster snarled back, loud enough for the whole carriage to hear.

I didn’t know whether to be angry or to try to soothe him. But after all, this was his land and I was the visitor here, so I softened my own tone of voice to ask, ‘Have I insulted you in some way? If I have, I’m sorry… But you play Brahms like a god…’

‘There’s no point insulting me. I’ll do any insulting there is to be done… I’m no young lad. Never mind my

size, I’m twenty-seven. Got that?’ he asked in a voice lowered to a half-whisper.

Now that staggered me.

So that’s the beginning of the story. As I’ve already said, he looked like a perfectly normal ten- or twelve-year-old boy. No anomalous features marked him out as a midget or a dwarf, no disproportionate limbs, no wrinkles on the face or anything of the kind.

Naturally, I didn’t believe him at first, and it was

obvious

from my expression.

‘Right, here, take a look at my passport,’ he said, tugging the document out of his inside pocket with a well-practised movement.

While he sold his

ayran

to women who fussed over him delightedly (‘Where did you learn to play like that?’ ‘Can you play “Dark Eyes”? How about “Katyusha”?’), I stood there like a fool, my eyes wandering between the official document and his face. Everything matched. Looking out at me from the photo was the unspoilt face of a child.

‘What’s your name?’ I asked.

‘Yerzhan,’ he replied curtly, jabbing his finger at the passport.

‘Can I buy… some of your… I mean some

ayran

?’ I gabbled in a rather ludicrous, apologetic tone.

Taking back his passport, he replied, ‘Brahms, you say? The last bottle, take it. I’ve sold the lot…’

We went into my compartment to fetch the money, and since the old man in the place opposite mine was sound asleep, I asked Yerzhan to take a seat, adding that it made no sense to stand when we could sit…

‘Does anything make any sense?’ he retorted, suddenly prickly again, and his question seemed to be addressed, not to me, but to this train galloping across the steppe, to this blazing steppe spread out across the earth, to this earth, adrift between light and darkness, to this darkness, which…

Yerzhan was born at the Kara-Shagan way station of the East Kazakhstan Railway, into the family of his

grandfather

, Daulet, a trackman, one of those who tap wheels and brake shoes at night and during the day, following a phone call from a dispatcher, go out to switch the points so that some weary old freight train can wait while an express or passenger special like ours hurtles straight through the junction.

The column for ‘Father’ in his birth certificate had remained blank, except for a thick stroke of the pen, and the only entry, under ‘Mother’, was for Kanyshat, Daulet’s daughter, who also lived at the way station (which everyone called a ‘spot’). The ‘spot’ consisted of two railway houses. In one lived, in addition to Yerzhan, his grandfather and mother, his grandmother, Ulbarsyn, and her younger son, Yerzhan’s uncle, Kepek. The second way-station house was occupied by the family of Grandad Daulet’s late shift partner, Nurpeis: his widow, Granny Sholpan, her son, Shaken, with his city bride, Baichichek, and their daughter, Aisulu. Aisulu was a year younger than Yerzhan. Nurpeis himself had fallen under a non-scheduled train.

And that was the entire population of Kara-Shagan, if you didn’t count the fifty or so sheep, three donkeys, two camels and the horse, Aigyr, all owned between the two families. There was also the dog, Kapty. But he lived with Aisulu most of the time, so Yerzhan didn’t think of him as his own. Just as he didn’t take into account the clutch of dusty chickens with a pair of loud-voiced cocks, since they multiplied and decreased in numbers in such a mysterious fashion that none of the Kara-Shaganites ever knew how many of them there were.

Multiplying in a mysterious fashion is a relevant point here, since in fact no one, except perhaps God, knew how Yerzhan’s mother, Kanyshat, became pregnant with him and by whom. Cursed by her father from that time on, she never spoke a word about it to her ‘immaculately conceived’ son. And all that Yerzhan knew – from what Granny Ulbarsyn told him – was that at the age of sixteen Kanyshat had run into the steppe after her silk scarf, which had blown off. The steppe wind lured her on, further and deeper, as if teasing her, on and on towards the sunset. And what happened after that was so fantastic that Yerzhan couldn’t make any sense of it. The sun was already

sinking

when suddenly it soared back up into the sky, glowing brightly. A tremor ran through the earth from the horizon. A whistling wind sprang up out of nowhere, then faded away for an instant, only to reverse its direction with a mighty rush so sudden that the dust of the steppe swirled up to the heavens in a black, hurtling tornado. And when Kanyshat, more dead than alive, discovered that she was

at the bottom of a gully, there standing over her scratched and bloody body was a creature who looked like an alien from another planet, wearing a spacesuit.

Three months later, when she began to show, Daulet, foaming with rage, brutally beat and cursed her for ever. If Kepek and Shaken hadn’t pulled the old man away from his half-dead daughter and dragged him to Granny Sholpan’s house, neither Kanyshat nor her son would have been long for this world.

Since that day Kanyshat hadn’t spoken a word.

Although Yerzhan’s mother was silent, the other women, and especially the two grannies, Ulbarsyn and Sholpan, loved to tittle-tattle, as Grandad Daulet called it.

Yerzhan recalled vicious winter nights. Whistling, windswept snow forced its way in through every crack in the window.

‘There in the ninth heaven grows Tengri’s sacred tree,

Kayin

, and hanging on its branches, like a little leaf, is the

kut

.’

Yerzhan had climbed into bed with Granny Ulbarsyn under her camel-wool blanket. She scratched his anus, which itched with little squirming worms.

‘What’s a

kut

?’ asked Yerzhan, still shivering from the cold. He was surprised by the similarity of this word to the word for ‘backside’ –

kyot

.

‘It’s happiness. It’s when you’re warm and well fed,’ Granny answered, and carried on with her story.

‘When you were going to be born, your

kut

fell off that tree into our house, down through the chimney. Everything follows the will of Tengri and our mother Umai. The

kut

fell into your mother’s tummy and in her womb it took the form of a little red worm…’

‘Is it him you’re scratching out of my backside?’

Granny tittered and slapped Yerzhan on his little cheek with the same wrinkled hand that had just scratched his backside.

‘You little chatterbox, sleep, or Mother-Umai will get angry and take away your

kut

!’

On another night the boy stayed at Granny Sholpan’s house because he wanted to be near little Aisulu, whose ear he had already nibbled so that he would marry her later. And this time Granny Sholpan told him her

version

of his conception and birth and wove a story about Tengri’s son, Gesar, into it.

‘Tengri sent Gesar to the earth, to a kingdom in the steppe where there was no ruler.’

‘You mean to us?’ Yerzhan immediately butted in. But Granny Sholpan’s fearsome glance cut him short.

‘So that no one would recognize him’ – the old woman pinched Yerzhan’s nose – ‘Gesar came down to earth as a frightful, snotty-nosed little scamp like you!’

Yerzhan started whining. His nose was hurting. And since Granny Sholpan didn’t want to wake up Aisulu, who was asleep in her cot next to them, she let go of his nose before she continued.

‘Only his uncle, Kara-Choton – the same kind of uncle

as Kepek is to you – learnt that Gesar wasn’t just an

ordinary

little boy, but heaven-born, and he started to bully his nephew in order to destroy him before he grew up. But Tengri always saved Gesar from Kara-Choton’s wicked tricks. When Gesar turned twelve, Tengri sent him the fleetest steed on earth, and Gesar won the famous horse race to marry the beautiful Urmai-sulu and conquered the throne of the steppe kingdom.’

‘Kazakhst—’ Yerzhan started to say, but stopped short when he spotted the sharp glint in Granny Sholpan’s eyes again.

She went on: ‘The bold Gesar did not enjoy his happiness and peace for long. A terrible demon, the cannibal Lubsan, attacked his country from the north. But Lubsan’s wife, Tumen Djergalan, fell in love with Gesar and revealed her husband’s secret to him. Gesar used the secret and killed Lubsan. Tumen Djergalan didn’t waste any time and gave Gesar a draught of forgetfulness to drink in order to bind him to her for ever. Gesar drank the draught, forgot about his beloved Urmai-sulu and stayed with Tumen Djergalan.

‘Meanwhile, in the steppe kingdom, a rebellion arose and Kara-Choton forced Urmai-sulu to marry him. But Tengri did not desert Gesar and freed him of the

enchantment

on the very shore of the Dead Lake, where Gesar saw the reflection of his own magical steed. He returned on this steed home to the steppe kingdom and killed Kara-Choton, freeing his Urmai-sulu…’

By now Yerzhan had warmed up nicely in Granny Sholpan’s cosy bosom and was fast asleep. In his dream,

though, he continued the adventure and rode the steed and freed Urmai-sulu.

Steppe roads, even if they are railroads, are long and monotonous, and the only way you can shorten the journey is with conversation. The way Yerzhan told me about his life was like this road of ours, without any discernible bends or backtracking. His story ran on and on, just as the wires outside the window ran from post to post, accompanied by the beat of the wheels’ hammering. He recalled his distant childhood running back and forth between his house and Aisulu’s house. Not only to look at the still-speechless beauty, whose ear he had nibbled in token of an early engagement, but mostly for the sake of his uncle Shaken’s glittering metal objects. Shaken used to disappear on his work shifts for months at a time. He worked somewhere in the steppe. But more about that later. Just as we shall talk later about Shaken’s television, which he brought back from the city.

But before that… Before that:

‘All women ever want to do is wag their tongues!’

Grandad

Daulet said, and tied the young tot on his back with his belt and climbed up on to his piebald grey horse. It was a spring day. Grandad left the railway line in the care of his son, Kepek, and they rode out into the steppe. They

galloped

in silence over the damp grass and tulips, galloping,

so it seemed, for no reason at all. And the wind, still chilly round the edges, scorched Yerzhan’s cracking cheeks.

They galloped as far as a gully with sparse hills

scattered

beyond it.

‘This is where we found you…’ the old man said.

And there beyond the gully with the noisy spring river at its bottom, on the far side of the wooden suspension bridge, barbed wire extended right across the steppe. Grandad reined in his exhausted steed and waved towards the fence with his whip. ‘The Zone!’ he exclaimed. And at that moment a fly started buzzing in the boy’s ear, a gadfly, the kind that circled above their cows on lazy days – a gadfly that became the droning word: Zone…

And the word began buzzing around in the child’s imagination.

Uncle Shaken worked as a watchman in the Zone.

The old man untied Yerzhan from his back and laid out the belt for both of them to sit on. He unslung his

dombra

from his shoulder and filled the ravine with the sound of his song:

When I am one, I’m in the cradle,

When I am five, I am God’s own creature,

When I am six, I’m like the birch pollen,

When I am seven, I’m the earth’s dust and its rot,

When I am ten, I’m like a suckling lamb,

And at fifteen I frolic like an elf and gnome…

How could Yerzhan have guessed then that this ancient song – God knows how it had come to Grandad Daulet’s soul – was about him, about his future life?

Gesar’s story had sunk deep into Yerzhan’s heart. And as Granny Ulbarsyn picked out from the boy’s hair the lice which had grown fat over winter, Yerzhan asked her about Gesar’s special features and how he could be recognized.

‘When Gesar was a frightful, snot-nosed little urchin, he didn’t have a willy,’ she replied, and hoped to have stopped her squirming grandson from pestering her further. She needed him to keep still for an hour or so to deal with the lice, and nits too, and then wash his head with sour milk.

Once that was done, she asked him to take off his underpants. She searched for the nits between the seams and clicked them to death between her fingernails. But Yerzhan could no longer wait. He ran off bare-bottomed to Aisulu behind her house. There they took turns to contemplate his tiny, wrinkly willy and compared it to snot-nosed little Aisulu’s enviable lack of any such item.

The boy also kept a close eye on his lazy uncle, Kepek, just in case he might try to bully his nephew. Kepek, however, spent most of his days sprawled on the only bedstead in the house, while at night-time he took his ageing father’s place at the points or walked round the night trains with the family hammer.

Sometimes Kepek came home in the early morning rip-roaring drunk and turned the whole house upside down without any rhyme or reason, swearing and cursing. Granny Ulbarsyn’s gasping and sighing woke Yerzhan up. And he was prepared for a sly beating from his own flesh and blood. But his uncle just shouted that he was going to leave this place for ever, that he was sick and tired of everything here, fuck this rotten life to hell! And then he leapt up onto his father’s grey horse and galloped off into the vast steppe just as the darkness was

dispersing

. And Kepek’s voice and his presence and his anger dispersed with it.

Granny Ulbarsyn’s story wasn’t the only thing that had sunk deep into Yerzhan’s heart. Grandad’s

dombra

-playing

stayed with him too. When no one was looking the boy took the instrument down from its nail high up on the wall. And while his grandfather tapped with the hammer on railway carriages, Yerzhan strummed the

dombra

secretly, imitating the old man’s knitted brows and hoarse voice. It didn’t take long before he picked out a few familiar melodies and then, with the keen eye he used to keep watch on Uncle Kepek’s behaviour, he followed and memorized his grandad’s finger movements. And the next day, when Daulet wasn’t there and Granny Ulbarsyn was visiting Granny Sholpan’s house, the boy zealously repeated the same run of the fingers. Very quickly and inconspicuously he learnt almost all Grandad’s repertoire.

But it wasn’t Grandad who caught him at it, and not even Granny Ulbarsyn. It was Kepek, who wandered into the wrong room yet again in a drunken state. How fervently he kissed every one of his little nephew’s fingers, how he slavered over them with his drunken spittle. ‘Ah, sublime dark power! Ah, sublime dark sound!’ he exclaimed,

swaying

his shaggy head wildly. That evening a slightly more sober Kepek gathered both families in front of the house and called his three-year-old nephew out of the door. The uncle announced that a concert was about to commence. And Yerzhan gave his first ever public performance, sitting in the doorway of his house.

His grandad was so moved that he retuned the

dombra

on the spot, changing from right tuning to left, from lower to higher, so that the boy could more easily sing along. He also now tutored his grandson every evening, recalling old melodies and ancient songs forgotten since the days of his youth. Within three months Yerzhan mastered everything that his grandad had accumulated in his entire lifetime – both melodies and verses. The little boy imbibed the centuries-old wisdom of the Kazakh, preserved in song, just as the steppe earth soaks up the rains of spring, transforming it into green tamarisk and feather grass, into scarlet poppies and tulips.

The high-soaring mountain is well suited

To the shadow running from it.

The deep-flowing river is well matched

To its meadowsweet-smothered bank.

The stout-hearted

djigit

is well suited

To the spear raised up in his hand.

The prosperous

djigit

is well matched

To the good he does for others.

The white-bearded elder is well suited

To the blessing of his retinue.

The affluent woman is well matched

To her plump goatskin of

kumis

.

The fresh young bride is well suited

To her little suckling babe.

When a maiden reaches the age of fifteen years,

More rumours are woven around her than braids in her hair.

The only one guilty of all this falsehood

Is the black sheep among her kin.