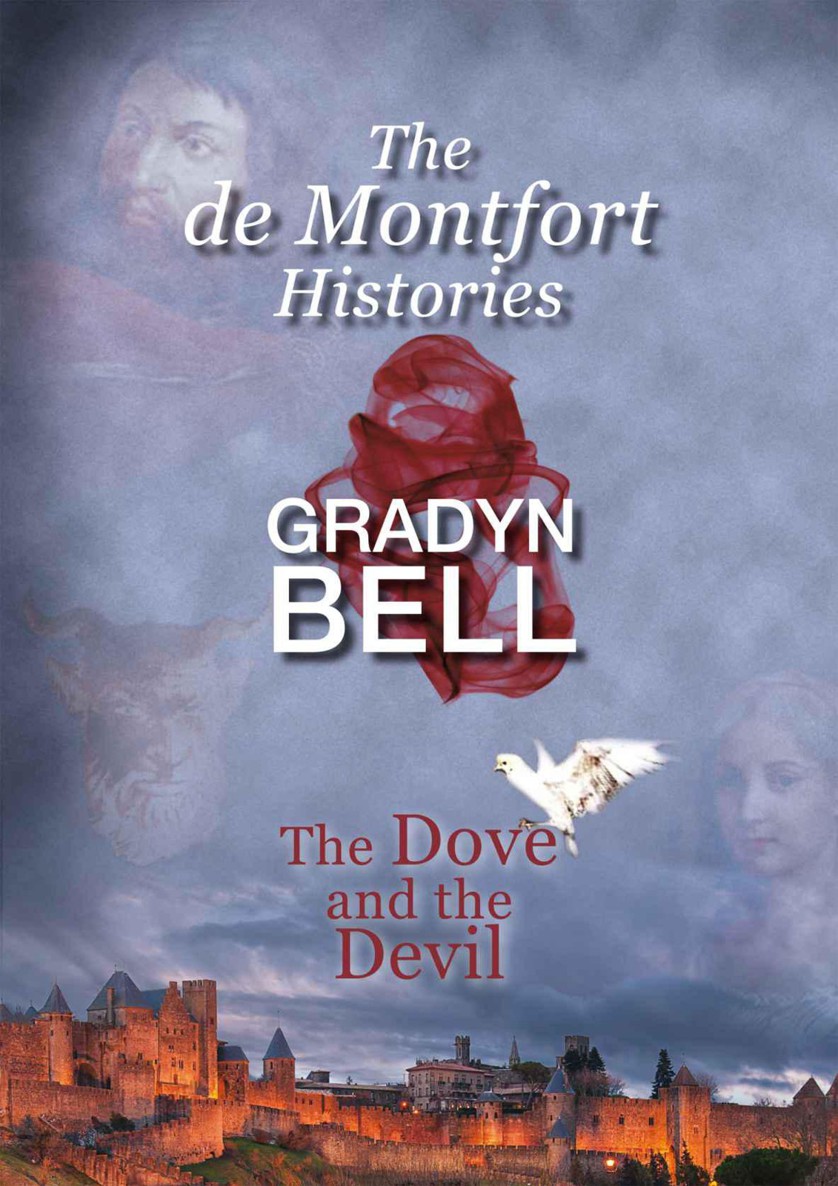

The de Montfort Histories - The Dove and the Devil

Read The de Montfort Histories - The Dove and the Devil Online

Authors: Gradyn Bell

The de Montfort

Histories:

The Dove and the Devil

GRADYN

BELL

About the Author

I now call England my home,

once again, after having travelled extensively and lived in England, France,

Canada and the USA.

From a young age, I’d wanted

to write and tell stories.

Years

of studying history, French and English, and reading - a great deal - give me

the perfect background for writing my historical stories.

I love to tell a tale and bring the

past to life in what I hope you will find is a vivid and compelling

manner.

I visit (and often live!) in

the places of that I write about.

The De Montfort Histories

begin with “

The Dove and the Devil

” where I was

inspired by the tragic tale of the Occitanian people in 12

th

and 13

th

century France.

Will goodness and

love conquer evil?

The Goodmount Chronicles

are centered in England and begin with “

The Lady of Lyngford

” and the sufferings

befalling the population during the time of The Great Pestilence (later known

as the Black Death).

How will life

be lived and love be found throughout this tumultuous time in history?

I would love to hear from you

– please email me at: [email protected]

All the best!

Gradyn

Contents

Setting the Scene: An Historical Note

List of Characters

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty One

Chapter Twenty Two

Chapter Twenty Three

Excerpt from

The

de Montfort Histories: The Dove In Flight

– Book Two of The de

Montfort Histories.

Setting the Scene: Historical Note

Most people, in England especially, but also around

the world have heard of Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester. Indeed there are

institutions and even a university named after him in England. The Simon they

have heard of is counted a national hero because of his work to bring

parliamentary rule to the people of England. He called his first Parliament in

1264. He was killed in 1265 at the battle of Evesham by Henry the Third’s son

who would later become Edward the First. The first book in the

de Montfort Histories

concerns itself

not with this Simon but with his father, also called Simon, and his younger

brothers, Amaury and Guy.

The de Montforts came from a fairly small estate in

Northern France. They were connected to the Earl of Leicester through Amicia de

Beaumont, who was Simon senior’s mother and the grandmother of the English

hero, Simon. At the time of the opening of

The

Dove and the Devil

, Simon senior had pledged himself to go on a Crusade to

rescue Jerusalem from the so-called Infidels.

As things turned out, the Crusade became a political

football rather than a religious experience for the Crusaders who had set off

for Venice where they intended to take ship for the Holy Land. Because they

could not pay for the ships they had requisitioned, it was suggested they

attack the nearby city of Zara where they would be able to refill their coffers

and pay their debts. Simon was horrified at this suggestion and he declined to

take part in an attack on a largely Christian city.

Following this the Pope called another Crusade in 1208

against a group of people who lived mainly in the South of France. These people

wished nothing more than to live in peace with their neighbours and worship in

freedom. They called themselves Christian but the Church in Rome called them

heretics.

It was the first time

ever that a Crusade has been called against a Christian people – although

it was not the first time a Christian city had been attacked by the Soldiers of

Christ, the Crusaders.

The Pope was convinced that the heretical peoples of

the southern part of France were poisoning the Church and weakening its

considerable power.

His very real

fear that the Church’s authority was being undermined drove him to allow his

flock - archbishops, bishops and priests - to pursue a course of human

extermination, which might very well be called the first documented genocide in

history.

These people, the Cathars (from the Greek, meaning

“pure ones”), were a group who could never agree with the doctrinal teachings

of the Church and whose beliefs predated those of the Church of Rome.

Their religion was pure and had not

become adulterated by powerful, money-seeking clerics.

The Cathars refused the sacraments of

the Roman Church; they gave women a place in society equal to men; they

insisted that to know God was to speak with Him personally through prayer, and

not through a priest.

The elders of the Cathar Church were great speakers

who refused to take shelter behind vague religious principles; they sought to

offer an explanation for our existence in clear and certain terms.

There were no mysteries in the Cathar’s

doctrine.

Everyone could have

access to the Almighty - the only requirement was to live as perfect a life as

possible.

It is true that the Crusade was patently about more

than religion.

The row was

political in the extreme, and the King of France had much to gain when the

independent area of France, now known as Languedoc, fell into his

clutches.

The Count of Toulouse -

premier baron of the area, and himself a cultured and learned man – was

one of the greatest princes of the western world.

Tolerant of the Cathars who lived in his domains, and indeed

tolerant of Muslims and Jews, he owed allegiance to kings and emperors alike,

but because his lands were viewed by the Church as a hotbed of heresy, they

were ripe for attack.

Simon senior, because he was remembered by the Pope as

the man of honour who would not attack the Christian city of Zara, was called

to lead the army and put down the heresy. The religious war became a war of

occupation, and by 1244, with the fall of the castrum of Montsegur, the heresy,

as well as most of the heretics, was all but dead.

The whole area, once rich, vibrant and above all tolerant,

became French.

The language of the

southern peoples, the

Langue d’Oc

-

language of poetry and songs of the troubadours – slowly but surely

became consumed by the language of the northern conquerors, the

Langue d’Oil

, the ancestor of modern-day

French.

Most of the characters in

The Dove and the Devil

were real.

I have ascribed to them feelings and thoughts which are

imaginary, though their actions are for the most part fact as we know it.

What was reported in the writings at

the time was largely biased in Simon de Montfort’s favour.

The destruction wrought by this man and

his armies in the name of the Church still rankles amongst some of the

population of present day Languedoc, the old Occitania.

I have heard people, to this day, refer

to him as the “The Devil” and he has entered into the folklore of the area as

the bogeyman with whom parents threaten their naughty children.

The Cathar characters, except for one or two, are

fictional.

Esclarmonde was real

and so was Dame Girauda.

Guilhebert de Castres was a famous Cathar bishop who did indeed

administer the consolamentum to Esclarmonde.

Depending on where the reader looks, Simon de Montfort

is portrayed as both an angel and a devil.

In truth he was only a man, a loving family man, who was

driven to excess by his religious ideals.

That these excesses caused so much suffering and the near extermination

of a people, is the price that has to be paid when moderation flies out the

window and we are blind to anyone else’s point of view.

As to the Shroud of Turin, there are many theories

regarding the origin and provenance of this piece of linen.

It is an historical fact that the

material with the so-called imprint of the body of Jesus Christ disappeared

from view in 1204 for a period of about 150 years.

It reappeared in France about 1357 in the hands of one

Geoffrey de Charny.

It has been

said that he was the nephew of

the

Geoffrey de Charny, Templar Master of Normandy, who had been burned at the

stake in 1314.

At the time of the main suppression of the Cathar

heresy (1208-1244), many Cathar noblemen joined the Templars and much of their

property was ceded to these bellicose religious knights.

Although the Templars pretended to

remain neutral during the Crusade, many of their high-ranking officials came

from Cathar families.

It is not

beyond belief, therefore, that the Shroud, having been rescued by one or more

Templar knights from the destruction of Constantinople, could have been brought

to Occitania – the present day Languedoc – in order to prevent its

falling into the hands of the Roman Catholic Church.

When the fortress of Montsegur finally fell in 1244,

it was said that a great treasure had been spirited away two weeks before!

I leave it to the reader’s imagination

to discern the identity of this great treasure…

Major Characters

Historical

Simon de Montfort

, Lord of Montfort L’Amaury, Northern France, a Crusader, “

The Devil

”.

Alicia de Montmorency

, wife of Simon de Montfort.

Amaury de Montfort

, eldest son of Simon and Alicia.

Guy de Montfort

, second son of Simon and Alicia.

Domingo da Guzman

, later St Dominic, founder of the Dominican Order.

Esclarmonde

, a Cathar Perfecta.

Raymond-Roger

, Count of Foix, brother of Esclarmonde.

The Count of Toulouse

, the principle nobleman of Occitania.

Arnold Almeric

, Papal Legate and religious leader of the Crusade against the Cathars.

Pope Innocent III

.

Count Thibaut

of Champagne.

Enrico Dandolo

, Doge of Venice.

Fulques de Neuilly

, Papal Legate who preached the Crusade of 1204.

Fictional

Maurina Maury

, a Cathar,

“The Dove”.

Arnaud Maury

, father of Maurina.

Pierre and Saissa Boutarra

, Maurina’s foster parents.

Pons Boutarra

, Maurina’s foster brother.

Bertrand Arsen

, a Cathar Perfectus.

Alain de Toulouse

, illegitimate son of the Count of Toulouse.

Prologue

Occitania, South of France, 1211

AD

Estiers dama Girauda qu’an en un

potz gitat:

De peiras la cubiron, don fo

dols e pecatz

Que ja nulhs hom del segle, so

sapchatz de vertatz

No partira de leis entro agues

manjat

—Guilhem de Tudele. La Canso de la Crusada.

The woman’s screams had finally ceased, silenced forever by the sheer

weight of the rocks which had been hurled into the well after her body had been

tossed there. A few of the soldiers standing around had the grace to look

discomforted, but most of them were smiling at the thought of a job well done.

Perhaps Dame Girauda had not minded dying; believing as she did most

firmly that this life was only one of many she would live. She had undoubtedly

received the consolamentum, as a Cathar of her standing would have done, and

had the soldiers not finished her off in their brutish way, she would likely

have starved herself to death anyway! As the inexorable tide of de Montfort’s

army had swept towards the town of Lavaur, she had never once doubted that her

life in this world was drawing quickly to a close.

When the crusaders had stormed her chateau, capturing hundreds of Cathar

heretics who had sought refuge there, she had begged for the lives of her

ladies. One of de Montfort’s more noble knights had promised them safe conduct

out of the town, but she had not lived to see him keep his promise, for she had

been turned over to the common soldiery to be used as they wished. They had

abused her mercilessly, several of them taking turns to rape one of the

greatest and most charitable women in Occitania. They had made her watch the

ignoble demise of her brother, Aimery of Montreal, as well as the company of

knights who had fought valiantly to withstand the month-long siege of her town.

Then they had begun to beat her. In the end, she, in common with the other

heretics, had welcomed death. It was this fact more than any other that had

annoyed the soldiers.

“As to dame Girauda, they threw her into a

well

And covered her with stones

This was a terrible crime for no one who

turned to her

Ever left her presence without help and

bread to eat.”