The Dark Sacrament (3 page)

Read The Dark Sacrament Online

Authors: David Kiely

The successful exorcists have one attribute in common: humility. They never brag about “their” prowess or achievements, never seek to impress. Each is at pains to establish that he is no more than a conduit, that he himself possesses no special “gifts,” be they of a spiritual or intellectual nature.

It is not hard to see a certain symmetry in this, once we accept the possibility of an evil force at work in the world, one intent on influencing the susceptible. To combat evil, then, there must be a

proportionately vigorous application of good. Such virtue is hard earned, not given.

The Rubrics of the Catholic Church prescribe that an exorcist “be properly distinguished for his piety, prudence, and integrity of life.” In his comprehensive study of evil,

Demons! The Devil, Possession and Exorcism,

Dr. Anthony Finlay sets out the qualifications necessary for a “suitable” exorcist. “In the face of often extraordinary situations,” he writes, “rare attributes are required in an exorcist, strong and unwavering qualities which will strengthen the chances of success in the fearsome battle against so great an evil.”

Preparation is of crucial importance. Spiritual fortification through prayer would seem an obvious prerequisite, but Finlay also stresses the need to fast before attempting the ritual. He is careful, though, to differentiate between the scriptural idea of fasting and our modern equivalent. “Fasting in the biblical sense,” he points out, “is not necessarily synonymous with the complete abstinence from food and drink, which itself would render the exorcist physically inadequate to the task.” Yet he goes on to assert that Christ's disciplesâthe fishermen and the others of modest meansâwere better candidates than most churchmen of our day, largely because the apostles, and those who came after them, turned their backs on excess. In our time, it is increasingly difficult to find clergymen who have not drifted far from these first principles.

We [priests] have become used to the comforts of society, and we find it difficult to give them up, even in such a cause as freeing someone from evil influences. How many of us throw away our worldly goods and follow Him, as Christ said was necessary?â¦Simplicity in behavior, frugality in manner, lack of ostentation and of any kind of excess was His rule. His disciples manifested these qualities and in this respect were much more suited to confront evil in possession of Man than we are today. How many of us can claim to live up to the rule or vow, at least in the

Roman Catholic Church, of voluntary poverty and scrupulous adherence to absolute obedience? It is precisely in these areas that many clergy of today are lacking. Days of prayer and fasting are regarded as too onerous and as a result lip service only is often given to the solemn occasion. We are not sufficiently prepared, with our desirable houses, cars, housekeepers, secretaries, money in the bank or schemes for making money, ambitions or whatever, for the enormous task of casting out the Devil.

Finlay ends on a cautionaryâand utterly chillingânote. He reminds us that the Devil can see through the exorcist who is unprepared, be it spiritually, mentally, or physically.

He [Satan] knows that underneath the show of bravado there is a soft underbelly, a weakness, a vulnerability which he can exploit. As a result he knows he it is who will emerge the victor. The unfortunate sufferer remains unchanged in all thisâif he is lucky. Often he is left worse off than before.

THE BATTLE FOR HEARTS AND MINDS

It was inevitable that a respected critic would emerge to debunk the whole charade of the unqualified exorcist. In 2001, Michael Cuneo, a Fordham University professor, published

American Exorcism

(with the wry subtitle

Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty

). It exposed the dubious practices of charismatic and evangelical preachers and their “deliverance ministries.” In a devastating broadside, he turned his attention to one such typically American organization, the Faith Movement. He identifies it as belonging to the same culture as “the tabloid television business, with its mock seriousness, its weepy sensationalism, its celebrity fawningâsoul food for the bloated and the brokenhearted.” Or to the shopping mall: the “community without contact, community contrived precisely to avoid contact.”

It is all too good to be true, he asserts, this fake American dream. It is “living, strutting, pulsating caricature: One almost expects it at any moment to break into a Bugs Bunny cartoon.”

The Faith Movement isâ¦a collage of American clichés. The preacher as snake oil salesman or used car salesman; the preacher as Vegas showman. Miracle-workers in pink Cadillacs and pinkie rings, soul-savers in three-piece glitter suits and sixty-dollar haircuts. This is the world of the Faith Movement. Gushing emotionalism, grasping materialism, tears on demand, hustles blessed with a thousand “Amens.” The product of old-fashioned hucksterism, New Thought optimism, and Southern-fried bornagainism, the Faith Movement is one of the fastest-growing enterprises on the American religious scene todayâand also one of the most wildly controversial.

Cuneo reports that he was present at a great many deliverances of the sort, and was not impressed. He reports that, in many cases, the participants witnessed what they claimed to be paranormal manifestations, but that at no time did he himself share their experiences. He concludes that mostâif not allâsuch banishments were either fraudulent or can more easily be explained in terms of psychiatric disturbance.

Cuneo had succeeded in polarizing the entire debate, leaving the general reader to ponder the question: Whom are we to believe? To many, the answer seems to lie midway between science and superstition. The aforementioned Dr. M. Scott Peck, who died in 2005, was perhaps the most notable among those who chose the middle ground.

In one of his early books,

People of the Lie,

the Harvard-educated psychiatrist alludes briefly to two cases from his medical files that forced him to reconsider his position on the preternatural. He recounts a particularly harrowing experience, during which a patient presented undeniableâfor Peck at leastâevidence of demonic pos

session. The disturbed young woman seemed to physically change before his very eyes. He recalls her face as wearing an expression “that could be described only as Satanic. It was an incredibly contemptuous grin of utter hostile malevolence.” Later Peck tried to emulate that grin in his bathroom mirror and found it impossible.

The change did not confine itself to the woman's face. Her entire body suddenly became serpentine. She writhed on the floor like a huge, vicious snake and actually attempted to bite the members of his team. “The eyes were hooded with lazy reptilian torpor,” he recalls, “except when the reptile darted out in attack, at which moment the eyes would open wide with blazing hatred.”

In the face of such a monstrous metamorphosis, the psychiatrist was forced to concede the existence of an external entity present in his patient. “I now know that Satan is real,” Dr. Peck concluded in his book. “I have met him.” He confessed also that, of the hundreds of cases he treated in the course of his professional life, a full 5 percent of symptoms presented by patients could not be explained in terms of present-day medical science.

In the conclusion to his final book,

Glimpses of the Devil,

Peck summed up his convictions, arrived at in the course of treating a young woman he called Jersey. Her case alone had effected his conversion from skeptical psychiatrist to believer in an entity that was the very personification of evil. His newfound belief went beyond faith; Peck knew with certainty that such an entity existed and furthermore had minor demons under his control. He wrote:

By the Devil, I mean a spirit that is powerful (it may be many places at the same time and manifest itself in a variety of distinctly paranormal ways), thoroughly malevolent (its only motivation seemed to be the destruction of human beings or the entire human race), deceitful and vain, capable of taking up a kind of residence within the mind, brain, soul, or body of susceptible and willing human beingsâa spirit that had various names (among them Lucifer and Satan), that was real and did exist.

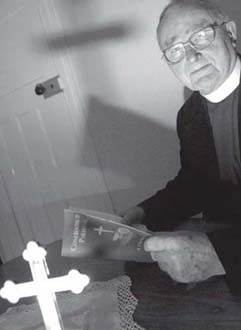

Image 2

Reverend William H. Lendrum

THE CANON: REVEREND WILLIAM H. LENDRUM

Canon Lendrum is quick to point out that his background, accomplishments, and ministry in the Church are in the category of the ordinary and commonplace. He makes no claim to any special favors or unusual gifts.

He was born in 1924 in Belfast of a working-class family. He describes his parents as “good people,” who were ambitious for their children but “not overly religious.”

At school, he applied himself diligently to his work and enjoyed sports. His realization that he must follow a spiritual path came soon after he entered university in 1943.

“I was studying commercial science at Queen's in Belfast, when I realized that I wanted to become a minister,” he recalls. “It was nothing earth-shattering, or anything like that. I simply understood the path I must follow in life.” He dropped out of the course and transferred to Trinity College Dublin. After six years' study, he was ordained an Anglican priest in 1951.

Two years later he married Leah. They have five daughters and thirteen grandchildren.

Since his ordination, Canon Lendrum has served in four parishes in Belfast, was a chaplain in four hospitals and chairman of the

Church's Ministry of Healing committee for many years. He began his deliverance and exorcism ministry in the early 1970s.

“I have to admit that there was a time in my life when I might have agreed with removing the Devil from the official teaching of the Church,” he explains. “I'd been brought up with a scientific worldview. I had never found it easy to grasp the concept of a being whom we call Satan, Beelzebub, or the Devil, whose purpose and aim was to lead people away from God and into sin and rebellion. Just as difficult for me to accept was the New Testament teaching which tells us that, under this being, there is an army of lesser beings called demons whose job is to control, influence, or destroy lives.

“I have no doubt that there are men within the Christian ministry, including bishops, who hold the same view. I cannot criticize them or impute blame, for that was my own vague notion for some years after my ordination.”

However, in 1974, when the minister turned fifty, he met a young woman who relieved him of all doubt that Satan was real.

“It was while I was carrying out my duties as chaplain in a Belfast hospital that I met Alice. She was in her twenties and had deep emotional problems. I prayed with her regularly, and she made the decision to repent of her sins and put her trust in God.

“She was discharged from hospital, and my wife and I helped out as best we could. Then one evening, I got a call from a parishioner whom Alice was staying with. The lady asked me to come over because Alice was being very difficult.”

Reverend Lendrum arrived and was shocked to find a very different Alice from the one he thought he knew. She was “scowling and ugly” and ranting loudly, hardly making any sense at all. Then he noticed something very odd about her speech. She was talking about herself in the third person, using she and her instead of I and me. It was the first indication that a demon, and not Alice, was doing the talking.

During that first exorcism, the minister was taunted continually by the demon. It would say: “You can't get rid of me, little man! You're

making a fool of yourself. She belongs to me. I knew her before you came along,” and so forth.

At one point, Alice fainted. When she came around, she asked why the minister was in the room. It was obvious that since his arrival, Alice had been shut out and the demon had taken her over, body and soul.

Canon Lendrum made inquiries into her background. He discovered that when she was younger, Alice had been initiated into a satanic cult. She had made vows to obey and serve Satan.

He decided that a major exorcism was called for. He gathered a small group of people, including a medical doctor, to assist him and succeeded in casting out several demons. But not all. Halfway through the ritual, Alice ran into a corner of the room.

“They're trying to take me away from you but they will not succeed,” she was heard to say. “I'm going to stay with you.”

“I knew then it was hopeless,” the canon says. “After that, she passed out of my influence. I'd see her occasionally, prostituting herself in the red-light district of Belfast, looking haggard and worn-out by a life destroyed by the demonic. She died in her fortiesâwas found lying in a doorway. Oh, you can't imagine the melancholy horror and sadness I felt when I heard that!”

During the past forty years, Canon Lendrum has seen a huge increase in interest in the supernatural. He believes that the more materialistic a society becomes, the more people turn to other philosophies to find meaning. He points to the New Age movement as an example of this alternative “soul searching,” and notes that the occult is more popular today than ever before.

“If people do not find what they need in the Church, they will look for it elsewhere. This is a serious indictment of today's Church because it means that we have failed to get our message across that Jesus is âthe Light of the world,' and that those who follow Him âhave the light of life.' We have failed to convince people that He is âthe bread of life,' who satisfies the deepest longings of the human heart.”

In his experience, demonic oppression is far more common than possession. At the same time, he concedes that those who are severely

demonized or possessed would be very unlikely to seek the help of the Church.

“I have no doubt that spirits can and do impinge on human life. They can play some part in causing (or more likely worsening) the things that trouble and depress humankind, but great care has to be taken not to give people the impression that they are âoccupied' or âin-dwelt' or âpossessed.' They may not be! It is one thing to be taken over or controlled by evil spirits who dwell within. It is another to be influenced or oppressed, from time to time, by spirits that are without. Indeed, it may be true to say that all of us have gone through the experience of being attacked from âwithout' at times and we have not realized it. The sudden argument that blew up on the way to church. An unexpected difficulty as we do something important for the Kingdom of God. A temptation that overwhelms us just when we thought we had conquered it! Malevolent spirits are always around to take advantage of our weaknesses.

“Spirits seem to have a channel to those who frequently suffer such attacks. The task of the exorcist is to rebuke the spirit and command it to depart, forbid its return, and seal up the channel it has established in the victim's life.”

Canon Lendrum is very clear on what qualifies an individual to carry out the work of deliverance and exorcism. Obviously, faith, courage, leadership, and authority are essential attributes, but “reluctance and a willingness to obey” he sees as necessary safeguards against a man getting involved for the wrong reasons.

“It is a mistake to believe that evil spirits and demons do not exist at all, and equally so to see demons under every bed. Both attitudes are as damaging to the witness of the Church and its healing ministry. It is the skeptic who believes only in what he can touch and see.”

He concurs with the wise words of C. S. Lewis in The Screwtape Letters:

There are two equal and opposite errors into which one race can fall about the devils. One is to disbelieve in their existence. The

other is to believe and feel an excessive and unhealthy interest in them. They themselves are equally pleased by both errors and hail a materialist or a magician with the same delight.

Canon William Lendrum is a unique individual. Well past retirement age, he is energetic and fearless. It seems that to the few clergymen courageous enough to assume the awesome mantle of exorcist, there is no such thing as resting on one's laurels. There is always that “one last case” to tackle.

The five cases that follow represent some of the canon's most harrowing brushes with evil.