The Daring Exploits of a Runaway Heiress (17 page)

Read The Daring Exploits of a Runaway Heiress Online

Authors: Victoria Alexander

BOOK: The Daring Exploits of a Runaway Heiress

2.86Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

“Do allow Mrs. Wiggins to tidy up on occasion.” Her tone was firm but a definite twinkle shone in her eye. Hard to believe but there it was. “I would hate to find you swallowed up by disorder upon my return.”

Phineas bit back a grin. “Faith, Miss West. One must always have faith.”

“And a broom would be helpful as well.” She opened the door. “Good day, gentlemen.” She took her leave, snapping the door closed behind her.

“It seems to me,” Phineas began slowly, “that if she is unaware that you have already begun writing and publishing your stories—”

“Then Lucy is unaware of them as well.” Cam nodded. “That is a relief.”

“Then do you plan to stop writing them?”

“Absolutely not.” Cam scoffed. “They’ve been quite well received and were not written by me, after all, but by Mr. Aldrich.”

“Ah, yes, that makes all the difference.”

Cam raised a brow. “Miss West was right about sarcasm, you know.”

“Then appreciate this.” Phineas crossed the room to his desk, opened the bottom drawer, and pulled out two glasses and a bottle of Scottish whisky. “There’s a flaw in your thinking.”

“I don’t see one.” Cam accepted a glass, Phineas filled it, and both men retook their seats.

“First of all, and as much as I hate to admit it, Miss West was right.” Phineas took a long sip of his whisky. “Whereas your fictional interpretation of Miss Merryweather might fool the world as a whole, she might be able to identify herself in your stories. I daresay Miss West could as well.”

“Nonsense.” Cam scoffed. “There are distinct differences between my fictional heiress and Lucy.”

“They are both American and both are on some sort of quest initiated by a dead relative.”

“They are entirely different.” Cam waved off the comment. “Mercy is trying to gain her financial independence so that she is not forced to marry a lout who only wants her for her money. Lucy already has financial independence. Her quest is more of a moral obligation.”

“And in the second installment didn’t our fictional heiress disguise herself as a harem girl and ride a camel to become part of a sultan’s traveling entourage in order to find one piece of the puzzle she is looking for?”

“A camel and a harem girl are entirely different from an elephant and an Indian princess,” Cam said firmly.

Phineas’s brow rose.

“Admittedly, there might be some similarities. . . .”

“Some?” Phineas snorted. “Parallels is more accurate.”

Cam ignored the sinking feeling in his stomach. No, Phineas was wrong. Lucy was sufficiently disguised. “Besides, as few people in London know Lucy and fewer still know of her quest, I am confident no one will connect my fictional heiress with Lucy.”

“Except, of course, Miss Merryweather herself. And very nearly as bad”—Phineas raised his glass—“Miss West.”

Cam grimaced.

“So in this confession you intend to make to Miss Merryweather . . .” Phineas studied his friend with barely concealed amusement.

What kind of friend took pleasure in the dilemmas of another? Cam brushed aside the fact that he would be doing exactly the same thing if their positions were reversed.

“You’re not going to tell her about the stories?”

“I don’t see why I would. It would simply be adding fuel to the fire. Telling her my real name and that I’m not an investigator but a writer is enough fuel to deal with already, thank you.”

“So when it comes to ambition versus affection . . .” Phineas eyed him thoughtfully. “It would appear ambition wins.”

“I wouldn’t put it that way.” Although Phineas did have a point.

“It seems to me if you’re going to eliminate the rather pertinent fact of your stories from your revelation, there is only one thing you can do.”

“I know.” Cam tossed back the whisky in his glass. “Make sure she never finds out.”

Chapter Ten

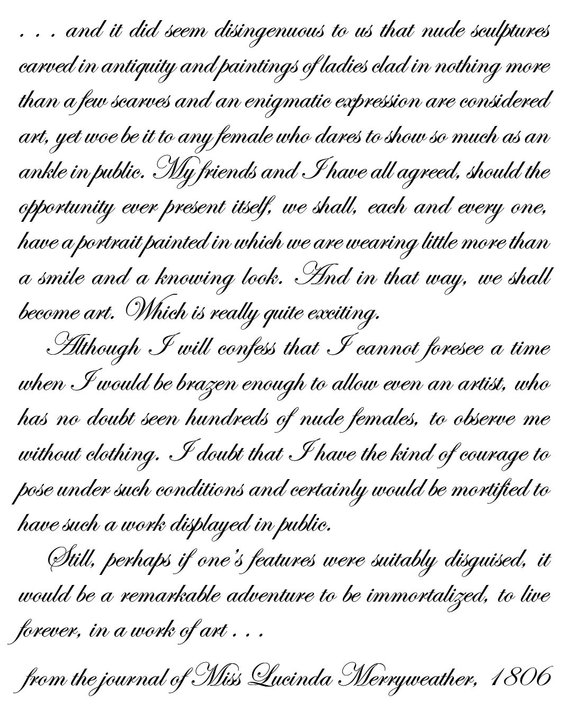

The butler directed Cam to the conservatory in a tone that should have given Cam pause, but he was far too concerned with rehearsing both his apology and his confession. Neither one was yet to his satisfaction, which was why it had taken until midafternoon before he finally arrived at Channing House. He had already learned to expect the outrageous from Lucy but he had never expected this.

It took him a moment to realize exactly what he was seeing. The conservatory soared nearly two stories. The outside walls were paneled with glass framed in iron, the floor paved with an intricate pattern of red and blue tiles. Condensation beaded on the glass. Moisture hung heavy in the air, pleasantly warm and scented with the rich smell of earth and the vague sweetness of flowers. Wooden benches here and there bordered a wide pathway leading to a large palm that grew nearly to the ceiling in the center of the room. A myriad of tropical plants competed for space amid lush greenery and exotic blossoms.

Several feet in front of the palm, slightly off to one side, a tall, dark-haired man stood before an easel, paintbrush in hand. A stool by his side was littered with paints and rags and all sorts of artistic paraphernalia. From the door, it was impossible to see exactly what he was painting.

Cam stepped into the conservatory and only then saw past the artist.

Lucy reclined on a blue brocade chaise, her elbow resting on the chaise’s arm, her head turned over her shoulder, her knees bent and stretched out to one side. Her blond hair was loose and drifted in waves to the middle of her back—

her naked back

.

her naked back

.

“Good God, Miss Merryweather!”

Her shoulders tensed, then relaxed. “Good day, Mr. Fairchild,” she said brightly. “I would know that outraged, indignant voice anywhere.”

“Are you mad?” He started toward her.

“I can hear you approach, Mr. Fairchild. Do not take one more step,” she said in an unyielding tone tinged with what might have been a touch of panic. “As you can see, I am posed quite carefully. I would be most embarrassed should you see more than I would prefer.”

“I have already seen a great deal!”

“Then consider yourself fortunate and turn around. At once, Mr. Fairchild!”

“Very well.” He huffed and turned.

“Your timing, Mr. Fairchild, is abominable,” she said coolly.

“My apologies!”

“Jean-Philippe has taken great pains to get me into this pose—”

Cam snorted.

“And I have taken great pains to make certain he did not see more than was necessary. It took longer than I expected, as he is extremely difficult to please for a man who is being paid for a service.”

“Thank you, mademoiselle,” the artist murmured in a heavily accented voice.

Another Frenchman? Where did she find them?

“Aside from arranging me to his liking—”

“No doubt,” Cam muttered. What was the woman thinking?

“—he rearranged greenery and fiddled with shading and angles and positions for what seemed like forever. I can’t tell you how many times he repositioned this chaise in order to get it just right.”

“One cannot simply throw paint on a canvas and hope for greatness, mademoiselle,” the artist said absently.

“Yes, of course,” she said, and Cam could hear the smile in her voice. “I would hate to go through all that again, Mr. Fairchild, simply because you have deigned to make an appearance in a flurry of shock and righteous indignation.”

Cam clenched his teeth. “Again, my apologies.”

“Accepted, although you don’t sound the least bit sincere.” She paused. “You may turn around now.”

“Thank you,” he snapped, and turned.

Lucy stood in front of the chaise, tightening the sash of what looked like a long men’s dressing gown. The silky fabric was patterned in hues of greens and blues, complementing and blending with the colors of nature in the conservatory. In truth, in that garment with her hair caressing her shoulders, the American looked like some sort of magical forest creature made of shadows and light who would fade into the foliage at any moment and disappear. He realized the robe had been draped low on her back when he had first seen her and had covered most of her legs. Most but not all.

She glanced at the artist, who ignored the interruption and was busy applying paint to canvas in a haphazard manner.

“I should have known this was your next

adventure

,” Cameron said sharply. The artist threw him a condescending look and Cam gasped. “You!”

adventure

,” Cameron said sharply. The artist threw him a condescending look and Cam gasped. “You!”

Lucy’s gaze shifted between the two men. “Do you know each other?”

The artist shrugged.

“Of course I know him! Bloody hell, if you were so determined to be painted sans clothing you could have found a genuine artist!”

“I assure you, monsieur, I am quite genuine,” the Frenchman said under his breath, not bothering to pull his attention away from his painting. “And very, very good.”

Lucy grinned.

“I hope you paint better than you bake!” Cameron snapped.

“I do not bake,” the man muttered.

Lucy stared. “What on earth are you talking about?”

“I’m talking about how you managed to find the one Frenchman who can bake as well as slap paint on a canvas.” Cameron crossed his arms over his chest. “At least I hope you are getting your money’s worth!”

Lucy shook her head in confusion. “What?”

“The resemblance, mademoiselle,” the artist pointed out. “You noted it yourself.”

“Oh, for goodness’ sakes, of course.” Lucy sighed. “Allow me to introduce Monsieur Jean-Philippe Vadeboncoeur—”

“Vad-eh-bon-kehr, mademoiselle,” the artist said in a long-suffering tone. “Vad-eh-bon-kehr.”

Lucy grimaced. “My apologies. Jean-Philippe is François’ brother.”

“He certainly looks like the chef !” Although now that Cam had a better look at him, he realized the artist was a bit older. And probably much more experienced at the seduction of young women.

“I have two other brothers as well, monsieur.” Vadeboncoeur stepped back from his work, studied the canvas, then continued to dab. “We bear a striking resemblance to each other and to our father.” He glanced at Lucy and a wicked smile shone in his eyes, then his attention returned to his work. “My mother says it is most convenient.”

Lucy choked back a laugh.

“This time, Miss Merryweather, you have gone too far!” Cameron huffed. “And please do me the courtesy of putting some clothing on.”

“Englishmen.” Jean-Philippe sniffed.

“I am more than suitably clothed, given the situation. And I quite like this.” Lucy glanced down at the robe. “It’s no worse than the sari.”

“That’s not saying much!” Cam couldn’t remember the last time prurient interest had dueled with honor and honor had won. “Good Lord, Lucy.” He strode toward her, shrugging off his coat. He wrapped it around her, jerking her closer to him in the process. “That’s not much better but . . . but . . .” His gaze locked with hers. His hands still gripped his coat and he stared down at her. He hadn’t realized just how intimate their position was. There was nothing between him and that delicious body of hers but the merest sigh of silk that clung to every curve, molded against her, and whispered upon her skin.

She stared up at him, the oddest look in her eyes. Of recognition or realization or awareness. As if she too knew the sudden and unrepentant longing, the ache of desire that surged through him, twisting his stomach and wrapping around his soul.

“I am nearly finished with you, mademoiselle,” Vadeboncoeur said.

The moment between them shattered and they jerked away from each other as if one or the other of them was ablaze.

Lucy cleared her throat. “Oh?”

“I will soon have all that I need of you.” The artist picked up a rag and wiped his brush, his gaze still focused on the painting. “A few hours, no more.”

“Are you nearly finished then?” she said.

He scoffed and gestured at the work. “No, no, there is much still to be done. The plants, the leaves, the way the light filters through the window and dances on the foliage and caresses the skin. But I will soon have enough to continue without you.” He nodded. “Such brilliance leaves me weary and parched. I must refresh myself. I shall be no more than a few minutes, then we will continue. Monsieur.” He nodded at Cameron, then strode out of the conservatory in search of refreshment.

“His English is better than his brother’s,” Cam noted. But like his brother, he too had the look of a god. A god somewhat older and probably more experienced and no doubt extremely skilled at—

“Why are you here?” Lucy asked the moment Vadeboncoeur disappeared from sight.

He drew a deep breath. “I came to apologize.”

“And yet your attitude today is precisely the same as it was two days ago.”

“Yes, well, that’s to be expected, isn’t it?”

“Is it?”

“Damn it, Lucy.” He ran his hand through his hair. “This isn’t some little lark, some silly antic. That man saw you

naked

!”

naked

!”

“Oh, he did not.” She paused. “Not much of me, anyway.”

“Have you no modesty?”

“I have a great deal of modesty. Why, I am probably the most modest person I know.” She huffed. “Let me tell you, Cameron Fairchild, it’s not particularly easy to pose without clothing. It takes a great deal of courage.”

He stared. “Courage?”

She nodded. “Yes, courage. At least in the beginning. But after a while . . .”

His eyes narrowed. “After a while?”

“After a while one realizes the artist is not really looking at you.”

“Come now.” He scoffed. “No man in his right mind would not be looking at you,

naked

, if given the chance.”

naked

, if given the chance.”

“Why, thank you, but that’s not what I mean.” She thought for a moment. “He certainly looked at me but with no more salacious interest than he would give a bowl of oranges or a vase of flowers. Once you realize that you are simply a subject like any other”—she raised a shoulder in a casual shrug—“then any sense of embarrassment goes away.”

“How delightful for you.” He glared. Had she no idea of the seriousness of all this? “Do you realize this is the sort of thing that destroys a woman’s reputation?”

“Only if people know about it and no one ever will. Besides, women pose for paintings all the time.”

“Well-bred, respectable, young women do not pose for paintings without their clothes on!”

She cast him an annoyingly wicked smile. “Which is what makes it an adventure.”

“Which is what makes it scandalous!”

“Nonsense.” She waved off his objection. “Scandal is in the eye of the beholder. Besides, I intend to keep the painting, not have it displayed in a gallery.”

“Which doesn’t mean no one will ever see it!”

“Which means no one will see it unless I wish them to. And even if they do, it will make no difference.” She paused. “Would you like to see it?”

He would like nothing better. “Absolutely not.”

“Come now, Mr. Fairchild, don’t be so stuffy. It’s art after all.” She strode over to the easel and studied the painting. “I think it’s quite extraordinary. Or at least it will be when it’s finished.” She glanced at him. “Are you sure you don’t want to see it?”

“No!”

Yes!

Yes!

Her attention returned to the portrait. “Even now there’s something about it that’s quite, oh . . . provocative.”

“To say the least!”

“I should tell you that I chose Jean-Philippe because of his artistic style.” She continued to inspect the work. “François had told me his brother was an artist, and yesterday Jean-Philippe came by to show me some of his work.” She glanced at Cam. “You would have known that if you had been here.”

He stared. “You told me not to come back.”

“And yet here you are.”

He hesitated. “Taking off your clothes is not the only thing that requires courage.”

“I had already decided to forgive you. You can’t help who you are, no man can. I have brothers, you know. It’s the very nature of your gender to be arrogant and overbearing and somewhat asinine.” She returned to her perusal of the painting. “In that you are no different than any other man.”

He stared. “Thank you?”

“Jean-Philippe considers himself something of an impressionist. Although he feels his work is progressing further beyond the mere depiction of a subject than even the impressionists went. Or something like that. It was a bit difficult to understand exactly what he meant; he did tend to go on and on, until I saw his work. That’s when I decided he was the only artist I could trust for this.”

“Trust?”

She pulled her gaze from the painting. “Are you certain you don’t want to see it?”

“Oh, very well.” He blew a resigned breath and joined her.

For a long moment he could do nothing but stare at Vadeboncoeur’s interpretation of a partially nude Lucy.

“He’s calling it

American Dreamer,

which doesn’t seem entirely accurate. I’ve always thought of myself as rather practical and sensible. But it does look a bit like a dream at that.” She glanced at him. “I can’t read your mind and for once your thoughts don’t show on your face. Tell me, what do you think?”

American Dreamer,

which doesn’t seem entirely accurate. I’ve always thought of myself as rather practical and sensible. But it does look a bit like a dream at that.” She glanced at him. “I can’t read your mind and for once your thoughts don’t show on your face. Tell me, what do you think?”

“I’m not sure what to think,” he said slowly. It was not at all what he expected.

The canvas was covered with dabs and dashes and dots of paint in what looked like a random manner. He took a step back, then another. The shapes took form the farther back he stood. It was definitely a woman in a lush, tropical setting, but it was indeed no more than an impression, a feeling perhaps of beauty and serenity and sensuality. It was obviously unfinished but was already most evocative, reminiscent of the works of a Monet or a Renoir, but not as refined and yet striking in a raw, abstract sort of way. More a vision than a truth, a dream more than reality.

Other books

Torched by April Henry

Summer's Temptation by Ashley Lynn Willis

Guerra y paz by Lev Tolstói

Crying for the Moon by Sarah Madison

Next of Kin by David Hosp

The Celtic Riddle by Lyn Hamilton

Falling Together (All That Remains #2) by S. M. Shade

The Dark Flight Down by Marcus Sedgwick

Sandra Hill - [Vikings I 01] by The Reluctant Viking