The Danube (40 page)

Authors: Nick Thorpe

Georg calls Josef, the chief forester. He turns down all offers of food and drink to tell his story. ‘I was born in December 1944. My father was a Sudeten German, my mother a local girl. When the Russians came, he was expelled. My mother and I stayed here. We were very poor. My mother got work looking after the cows for a local landowner, on the far shore, at Haslau. We had a couple of goats of our own, so we could always drink goat's milk. I remember as a child, how much I longed for cow's milk. Now I find out that goat's milk is better for you anyway! … The Russian soldiers used to come down to the shore to catch fish. They were always very kind to us, even shared their bread with us. I remember it was black, very different to ours, and had a funny taste. They had a very crude way of

catching fish. They would throw a couple of hand-grenades into the water, and the explosions killed lots of fish and brought them floating to the surface. Then they would gather them in big boxes, load them into the back of their trucks, and drive away again. What the Russians didn't realise was that the bigger fish, that were just stunned by the explosions, only floated to the surface an hour or so later. So we children would take those home. Or take them to the restaurants to sell!’

His first income, at seven years old, was from selling fish to the restaurant outside which we now sat. Then he got a job in forestry, on the same estate as before, which in the meantime had been nationalised. ‘As a forester?’ I ask. ‘A wood-hacker, rather!’ he grins – the lowest of the low. He learnt to plant fast-growing trees in straight lines, and was even sent to Novi Sad and the forestry school in Osijek, to learn how to grow trees even faster, even straighter. ‘The speed was all that mattered. Plant them, watch them grow, bulldoze them all down, plant new ones.’

When the protests against the planned Hainburg dam broke out in the early 1980s, and the Austrian prime minister granted a ten years' pause for reflection, Josef was suddenly out of work. He and his colleagues would have had the job of clearing all the forests on both sides of the river, to make way for construction – the same trees which the young Austrian environmentalists were climbing and chaining themselves to, to stop the bulldozers. So Josef started commuting to Vienna, where he got a job in a bread factory. In the meantime at Orth, 110,000 people pooled their savings to buy the forest to create the national park. One day Josef got a phone call from the director. Would he meet him for a drink? Over a cup of coffee, in middle age he was offered the task of undoing his life's work, of helping the forest return to something like its natural state, of overseeing the removal of artificial barriers, the natural reflooding of the forest and the destruction of the straight lines of his youth. The one thing he, as forestry manager, was no longer allowed to do, was to plant or cut down trees. ‘It was strange at first, very strange. You have to look at trees in a very different way … letting them grow by themselves, fall by themselves, slowly rot into the forest floor. And the most amazing thing was, as we let this happen, how all the wildlife re-appeared in the forest.’

Another man cycles by and Georg calls him over. Martin has long hair, partly hidden in a woolly hat. He's on his way home after a hard day's

work, but spares us some minutes. Martin and his wife have just finished restoring a water mill, now moored on a creek a few kilometres upstream. How had they done it? With passion, he says. And madness!

While we talk, Georg is feverishly tapping the keyboard of his mobile phone. ‘She says yes!’ he suddenly announces, excitedly. He has just arranged for me to go owl-spotting with the girls tonight. So as darkness falls I find myself in the pleasant but rather unexpected company of Christina, who is writing her PhD on owl behaviour, and a Latvian student on work experience, bouncing down a dark track, ever deeper into the forest. At one point a whole herd of deer – I count at least eight – is scattered by our approach, leaping lightly away down the sides of the grassy dyke, some to the left, some the right. We stop, watch them regroup cautiously, then walk peacefully away into the forest. A little while later we take a right turn, down into the forest again, until we reach a clearing which Christina reconnoitred earlier. There she sets up her own recording and broadcasting equipment. The plan is to play the calls of different kinds of owl, so that real owls living in the wood will assume their territory has been infringed upon and will come to examine the intruders. It's a starry night, but only a small pool of stars is visible above the ring of trees. First Christina plays the sound of a male tawny owl. The cry is long and mournful, the recording one of her own. It echoes through the forest, like ripples in water. I imagine the ears of the entire forest twitching in response, including fellow owls and their prey. But there is no reply. Next she tries the call of an eagle owl, a bigger, fiercer bird. Almost immediately, a long, low hoot comes in response – but of a different note. ‘It's a tawny!’ she whispers. Now she turns on the recording equipment, which looks like a small, curving satellite dish. Soon it is calling, closer and closer to us, though its wing beats are completely silent. As it approaches, we hear the higher pitch of a female tawny, following the male through the forest. Then the two of them settle, effortlessly, in the tree next to us. We can see them clearly outlined against the starry sky. A few nights earlier, on a similar expedition, an eagle owl flew so close over her head she had to duck down, she says.

Every owl, not just every kind of owl, has its own voice, and she has trained her ear to recognise individual birds, Christina explains. She makes careful notes in a log book, complete with GPS coordinates, and the sounds which attracted each owl in turn, with the light of a spotlight

attached to her forehead. A thin, pretty girl, humorous … birdlike. We make some more owl sounds, record some more. While waiting for the owls, our eyes peeled on the heavens, we identify the constellations. The tawnies we saw were just under Gemini, twin stars blinking in the darkness. The girls will stay out all night in the forest, going from place to place, but I should press on, to Vienna. They drive me back to my car in the village of Stopfenreuth. ‘How did you get interested in owls?’ I ask. ‘I am an owl,’ Christina says simply, with only a trace of a smile around her mouth. ‘I don't need to sleep at all at night; I like to sleep till midday …

We bid one another birdlike farewells; the girls go back to their dark wood and their birds of prey, and I plunge across the Danube bridge towards the highway and the bright lights of the Austrian capital.

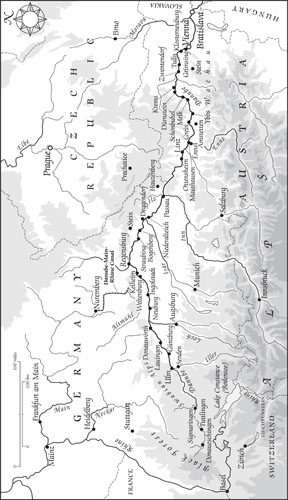

4. The Upper Danube from the castle at Devin to the source of the river in the Black Forest.

CHAPTER 12

Danube Fairytales

‘Man, a god when he dreams, barely more than a beggar when he thinks.’

F

RIEDRICH

H

ÖLDERLIN

1

T

HE

N

ASCH

market in Vienna is a double line of stalls, like the floats of a fisherman's net, but the net itself is lost in the depths of the River Wien which gave the city its name, then disappeared beneath its streets. There's the Theater an der Wien on the corner, to remind market-goers that they are walking on water. The market, like most of Vienna, is far from the Danube, which bypasses the city like a cruise ship in the night. It was named after the ash wood containers in which the milk once sold here was stored. It boasts an elegant fish market, though none of the fish here actually come from the river. The Wien river survives, just about, in its concrete tunnel, and funnels out into the Danube canal.

Each fish on display carries a neat tag with its country or region of origin, like a Miss World contest. There are

Saibling

– char – from Mariazell, carp bits for fish soup from the Gut Dornau in Lower Austria,

Hecht

– pike – from the Neusiedler lake on the border with Hungary and trout from Salzburg. Everything else is imported from other seas: salted cod and Coquilles St Jaques and Venus mussels from the north-east Atlantic, eight different kinds of caviar, including sturgeon eggs from the Caspian, and even deep-frozen pikeperch – an authentic Danube fish – from Kazakhstan. At the downmarket end of the fish-stalls, a young man from Negotin in eastern Serbia stands over a green tub in which six muddy

and rather lost-looking carp swim to and fro – from the Czech Republic, he says, as though that explains their demeanour. Negotin is a town not far from Miroč, to which Marko Kraljević pursued the fairy who killed his friend Miloš. The man has been in Vienna for twenty-three years, which must mean he was almost born here – his parents wisely got out of Serbia soon after Slobodan Milošević came to power. A pointy-faced man with blue eyes and an unshaven chin sells

Wanderbrot

– Dick Whittington food – delicious, compacted dried fruit, ideal for long journeys. I buy a big chunk for the road. ‘I'm from the Soviet Union,’ the man announces, a country which, according to my calculations, has not existed for more than twenty years. When I gently point this out, he confesses that his homeland is actually Uzbekistan – ‘but no one here has ever heard of it.’ If I came from the legendary city of Samarkand, I tease him, I would proudly tell the whole world about it at every opportunity, and thereby win extra custom for my stall.

An elderly Austrian man sells red wine from Montenegro and white wine from Mostar, where the River Neretva flows deep and turquoise beneath the single arch of the repaired bridge, even when the sky is the dullest shade of grey. The stall has been in the family since his father bought it in 1965. And how's business? He frowns. ‘Euro-teuro …’ – a mocking reference to the European currency which has made everything more

teurig

(expensive). He grumbles about the gentrification of the market, the little cafés springing up everywhere. Just above his head I spot

chai tou vounou

– Greek mountain tea, in its traditional plastic bag – and snap up a couple of packets. I used to buy it by the armful in the marketplace in Istiea in northern Euboea, but apart from rare finds like this, it remains one of Greece's best kept secrets, or worst-marketed treasures.

Then along the Franz Lehár alleyway to the Café Sperl.

2

The ghost of Franz Lehár sits at a table near the entrance, putting the final touches to the score for the ‘Merry Widow’, fated to become one of Hitler's favourite light operas, to its composer's misfortune. What did the German dictator think as he sat listening in the dark of the concert hall; what passed behind his closed eyes? Lehár was born on the north bank of the Danube in what is now Komárno in Slovakia. In 1902 he became conductor at the Theater an der Wien, and the Sperl was the nearest place to retire for a quiet drink

to compose his next work. His wife Sophie was of Jewish origin; she converted to Catholicism but nonetheless drew the hostility of the Nazis. Hitler is said to have intervened personally to end the machinations of those who wanted her deported to the death camps, because he was so fond of her husband's music. Another ghost at the Sperl tables is Lehár's fellow Hungarian Emmerich – or Imre – Kálmán. A talented pianist and composer, he worked closely with Lehár, then escaped the Nazis in 1938, first to Paris, then the United States. Hungary has furnished western Europe with so many exiles.

Miklós Gímes, a Hungarian journalist and son of the 1956 revolutionary of the same name, once told me how he fled Budapest in November 1956 as a child of seven with his mother, leaving his father behind as the Soviet troops re-invaded the country. And how his mother took him to a smart Viennese café like this one, and spent the last of the coins the Austrian Red Cross had given them at the border on cakes. As they sat there, in their long, unfashionable coats, clutching all their possessions in a single suitcase, the Viennese middle class studied them like creatures from another planet, then one by one came to their table and gave them money.

The Sperl, with its old wooden tables, and rather brusque and beautiful waitresses, is definitely conducive to writing. Between slices of cake I trade limericks with a friend:

‘The national game of the Czechs,/is not what a person expects./This peculiar nation,/thinks defenestration,/is far more exciting than sex.’

‘An ancient fish is the pike,/his long faces are never alike./When I slept in Vienna,/I awoke in a terror,/that a pike might alight with my bike!’

The military museum is a sturdy red brick fort five stops on the metro from the Nasch market.

3

The first floor is lined with exhibits from the two Ottoman sieges of Vienna, in 1529 and 1683, and from the mopping up operations which followed: the capture of Párkány and Buda. The arrow that lodged beneath Count Guidobald von Stahremberg's shoulder during the siege of Buda is preserved at the centre of a glass monstrance, above the figure of a turbaned Turk who kneels in heavy chains with three dogs snapping at his heels. There is an accompanying verse: ‘Ein Pfeil, so zwanzig Jahr in Fleisch und Bein gesteckt, und tausend-fachen Schmerz dem Helden Leib erweckt, wird durch des Künstlers hand von seinem Sitz

gebogen, und nach gemachten Schnitt noch glücklich ausgezogen.’ (‘This arrow lodged for twenty years in a hero's flesh and bone. It tortured him much, but was happily cast out by a surgeon's skilful craft.’) Guido was the cousin of the commander of Vienna's defences, Ernst von Stahremberg, and distinguished himself by his bravery, leading sorties out from the walls to attack the besieging Turks. He was seriously injured during a desperate attempt to stop the Turks storming the city after blasting a hole in the city wall. When he was struck by that arrow at Buda, just three years later, he must have thought his final hour had come.