The Danube (30 page)

Authors: Nick Thorpe

Mustafa Zade, also known as Köprülü the Virtuous, was one of the better Turkish Grand Vizziers of the seventeenth century, and it looked for a while as though he might reverse the decline of the Ottoman empire's fortunes. The siege of Vienna had failed utterly in 1683; Buda was lost in 1686. In 1690 Köprülü advanced at the head of a large Ottoman army and retook Niš and Belgrade. In the summer of 1691 he marched north beside the Danube from Belgrade to meet the Austrian Prince Ludwig, who came south from Petrovaradin. They met at Slankomen. Turkish superiority on the river failed to compensate for the better armed, better commanded Austrian army on dry land. A deadly barrage of musket fire met each successive Turkish charge. ‘When defeat appeared imminent Köprülü himself, hoping in the last resort to save the day, led a desperate charge. Calling upon Allah, he cleared his way with a drawn sword, flanked by his guards, through the ranks of the Austrians. The heroic gesture was in vain. Their ranks stood firm. He was hit in the forehead and killed by a bullet. His guards saw him fall, lost courage, and fled. His commanders, who might for a while have concealed the news of his death from the troops, broke into lamentations and allowed it to spread, thus undermining morale and creating a general panic,’ wrote Patrick Kinross.

17

‘For the Ottomans, the death in battle of their last shining hope … was a crucial disaster. Hungary was lost to them. So … was Transylvania.’

Stari Slankomen shimmers in the summer haze, a clutter of red-roofed houses along the shore, and a tall church on the higher ground. Just opposite, the blond Tisza, known higher up as the black and the white Tisza, high in the Carpathians in Ukraine, flows into the Danube. The Tisza was poisoned by a spill of mercury from the gold mine at Baia Mare in Romania in January 2000. Almost all fish life along five hundred kilometres was destroyed. Some heavy metals flowed into the Danube, but the main damage was to the Tisza.

18

In May 2011, as I travelled up the Danube, the Bosnian Serb military leader Ratko Mladić was arrested in Serbia after sixteen years in hiding. I had seen his handiwork in Bosnia and well knew the fear the families of his victims had of him, and of the adulation of his former soldiers. Unusual among officers, he always personally led his troops into battle. That meant that whenever atrocities were committed, he was never far away. In July of that year I am invited to the house where he was caught, in the little village of Lazarevo, not far from the Tisza and Danube rivers. Branko, Mladić's second cousin, sits in the shade under a mulberry tree. There's plum brandy on the table, and fizzy juice for the driver. Branko's neighbour, Nenad, is the first to speak. ‘It was five o'clock in the morning. I'd just walked over to Branko's garden to water my peppers, the big red ones which we call “elephant's ears”. When I looked up, there were policemen everywhere – in uniform and plain clothes. “What's up?” I asked. “Did someone die? Or are you here to buy a pig or a lamb? – Branko has both.”

Neither, they replied. “We need you as a witness, for a house-search.”’

Ratko Mladić was well known and well liked in Lazarevo. Many simple, rural Serbs regard him as a man who won battles, and who was on the run for sixteen years, not from justice, but from anti-Serb sentiment in the world. Atrocities like the three-year siege of Sarajevo, the shelling of civilians, and the cold-blooded killing of thousands of non-combatants at Srebrenica, tend to be either disbelieved, or quickly glossed over in such company. The more so since Mladić has many relatives in Lazarevo and, as it turns out, was a regular visitor both in his army years and since, when he was the world's most wanted man after Osama Bin Laden. In the early 2000s, Mladić even kept bees in the village. At that time, armed bodyguards stood close by, to discourage any attempt to seize him. ‘Your gun is showing,’ Nenad, ever the joker, told one of them at that time. ‘It's meant

to be showing,’ the man told him, pointedly. Interestingly, the Serbian police never showed any interest in the village, fuelling theories that the state security organs knew very well where he was all those years, but chose to leave him in peace. A week before his arrest, Mladić's son Darko visited Lazarevo for the feast day of Saint George. The general was ill, his supporters had run out of money, and he was tiring of a life in hiding. The absence of commandos, and the peaceful, almost routine, nature of the whole operation, give the distinct impression that it was all arranged in advance, with Mladić's agreement.

‘I am the man you are looking for,’ he announced, as the police walked into his room. Seated in his track-suit, one arm limp from a stroke, the general was sarcastic, but polite to them, who seemed amazed to find their quarry here. ‘Which one of you is the American?’ he asked. ‘Who is the one who killed my daughter?’

The suicide of his twenty-three-year-old daughter Ana in 1994 may have tipped the scales in Mladič's mind and turned him from a rational, ruthless soldier into an irrational military leader, capable of mass murder.

They found two pistols in the cupboard, American made. When the police inspector asked him about them, Mladić said one was a gift from a volunteer in the war. Mladić tried to reassure the police that he had no thought of escape or of violence. ‘If I had wanted to, I could have killed ten of you, because you were just one metre from my window. But I didn't want to, because you are young people, and you are just doing your job.’

By nine that morning, Mladič was sitting in a black jeep, being driven to the War Crimes court in Belgrade. Within a year, he was on trial for genocide and other crimes against humanity at the International Tribunal in the Hague.

The police stayed on in the village, and Nenad with them. ‘This all looked to me a little bit like a circus. When I see the thief caught on television, with a couple of cartons of cigarettes, there are the special police with their long-barrels, breaking down the doors and everything. But here there was none of that, I told them. But they just smiled at me. “No comment” was all they would say.’

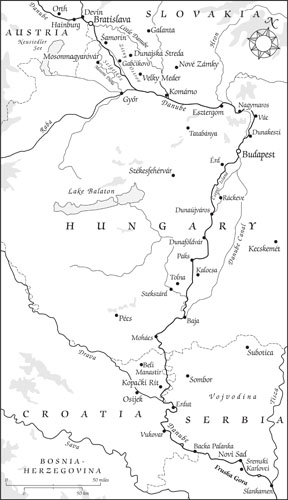

3. The Upper-Middle Danube, from the Fruşka Gora hills in Serbia, across the Hungarian plains to the foot of the Carpathians in Slovakia.

CHAPTER 9

The Black Army

One fortunate morning, when the edge of the sky was tinted by the pink of dawn's blood, when the moon turned its flag around, and the black army rose; when the dawn showed its pink face, and a wound appeared on it like the cut of a sword …

K

EMAL

P

ASHA

Z

ADE

, poet in the court of S

ULEIMAN

the Magnificent

1

T

HE

C

LOCK

tower in the castle at Petrovaradin, the fortress on the right bank of the Danube in Novi Sad, has four wide faces, so that those on ships passing on the river below can always tell the time. The Danube cuts a long, pensive meander through the city, as though uncertain whether to stop for the night or move on. The little tower reminds me of the lighthouse in Sulina at the start of my journey. The big hand has three white grapes, the little hand two, against the black of the clock. There's a golden globe on the top with a weather vane, but no wind this July day to take the edge off the summer heat. The hands hardly leave a shadow on the faces of the clock.

The fortress on its rocky outcrop was home to the first known settlement, by a Celtic tribe. They were displaced by the Romans, who valued the defensive possibilities of the place. The ‘Petro’ in the name comes from a Byzantine bishop called Peter. In 1526 Suleiman the Magnificent marched with his army to the decisive battle with the Hungarians at Mohács. Taking the town, he told his Grand Vizier Ibrahim, would be ‘like a snack to keep him going before breakfast in Vienna’.

2

In fact it was

not quite so easy, but when the Turkish soldiers blasted two holes in the walls by attaching mines, resistance crumbled. Five hundred of the defenders were beheaded and three hundred taken into slavery. The criteria for deciding their fate is not known. The Serbs had to wait till 1716 for their revenge, when Damat Ali Pasha was defeated by Prince Eugen of Savoy. He tried to rally his forces with a charge straight into the Austrian ranks. His reckless bravery and death were much like those of Mehmed Köprülü at the battle of Slankomen. Damat Ali did not die on the spot, however, and was carried, mortally wounded, on horseback by his troops to Karlowitz – Sremski Karlovci – and died there. In the garden of the Church of the Lower Town in Sremski Karlovci an enormous white plane tree stands, one of the oldest in Europe, planted exactly three hundred years ago when the church was built. Perhaps Damat Ali the Dauntless breathed his last in its teenage shade. Not to be outdone, the Orthodox seminary nearby boasts a magnificent yew of similar girth and vintage – the plane almost white with age, the yew dark and green and brooding.

Novi Sad is Serbia's second city, proud of edging ahead of Niš in the south, and proud above all of its position, straddling the Danube, a rich modern city, the Birmingham of the Balkans. The heat of summer, the cheap ice-cream and beer, make it lighter and brighter than Belgrade, and the agricultural wealth of the province of Vojvodina makes it the most prosperous in Serbia. In the 1960s and 1970s it became a mecca for the pop-starved youth of eastern Europe. The denim-clad teenagers of Yugoslavia had an easier time of it than those kids of Ruse who had to watch their priceless vinyl records being smashed to pieces by border guards. ‘Yugoslavia became the most powerful rock'n'roll country in the region,’ wrote Vladimir Nedeljković in his book

The Danube Girls and Boys

.

3

Radio Novi Sad had a powerful transmitter that reached across the satellite states of eastern Europe and deep into the Soviet Union. It broadcast first jazz, then beat music. 1964 was the turning point. ‘All over Europe that year, the Baby Boom generation started to build a new world on the ruins of the history and politics of the Second World War, personified by Joseph Stalin in the East and Sir Winston Churchill in the West … The standard of living was high, the country was open, foreign rock magazines were available everywhere … So much lucidity, wisdom and goodness take place only once in a hundred years.’

4

By the end of the 1970s, the

hippy culture was turning to punk, and Novi Sad had its own band, Pekinska Patka. ‘Nobody had thought like that before them. No one had played like that before them. Nobody had looked like that before them.’

The dreams of the 1960s and the rude rebellion of the 1970s turned sour in the 1990s. Young men fled into exile rather than fight Slobodan Milošević's wars. Many who stayed were killed or wounded on the battlefields of Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo. The crowning disaster of the decade came in 1999, when Novi Sad received special attention from NATO. Three bridges over the Danube, the oil refinery and many electricity transformers were hit. The Varadin Bridge, constructed by German prisoners of war in 1946, was the first to fall, just before dawn on 1 April 1999, the seventh day of the air-strikes. Liberty Bridge, the most modern, completed only in 1981, was hit by three missiles on the evening of 3 April. The Žeželj bridge, built in 1961 and named after its architect Branko Žeželj, proved the most resilient. The first missile struck on the night of 20 April, but it needed another direct hit, on the night of the 25th, to knock the last twisted metal supports into the swirling Danube. There is a seventeen-second black-and-white video, posted on YouTube, of the final blow, filmed from a camera in the nose of the missile. The final frame explodes in a fuzz of black-and-white particles. One of the jokes circulating in the city immediately after the bombing was that Novi Sad was the only city in Europe where the river flows

over

three bridges.

The task of rebuilding began even before the war ended in June 1999. The Serbs wanted the West to pay for the damage, as compensation for ‘the aggression’. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development put up some of the money. Slobodan Milošević arrived at the opening ceremony on the Beska motorway bridge over the Danube. ‘Dear citizens of Novi Sad, dear citizens of Vojvodina, dear bridge builders! The worst eleven weeks since World War II are behind us, in which the most brutal aggression was carried out by the largest military machinery ever created in the world.’ The Beška bridge would be rebuilt within forty days, Milošević promised – the magic forty again – because its building blocks were prepared ‘even while the bombs were still falling’.

5

Thirty-nine days later, traffic was rolling over Beška once again. The three bridges in Novi Sad took longer. I sat in a small motor boat filming the ruins of Liberty Bridge a few months after the war. The pilot grew increasingly nervous. The huge

chunks of concrete that had fallen into the water created unpredictable whirlpools as the Danube swept over them. We had to cut the engine for me to speak into the camera. Each time I had to repeat my words the danger increased.

Up and down the river, shipping companies fumed about the unexpected interruption to their trade. The United Nations-imposed sanctions against Yugoslavia in the early 1990s had been bad enough, with sudden searches of barges by international monitors looking for oil or weapons. But now the Danube was impassable, at first because of the dangerous debris, and then on account of the temporary pontoon bridge the city authorities threw across the river to reconnect the two halves of their town. For ships to pass, this had to be opened up completely. Once a fortnight, at first, when a long queue of barges had built up, then once a week. The wine exporters of the Ruse region were just one of the injured parties. Sending their wines to their favourite markets in Britain and Scandinavia, by road or rail as opposed to ship, was adding about 20 per cent to the retail price, Danail Nedjelkov, the Bulgarian member of the Danube Commission, told me at the time. That extra cost destroyed the place they had won in the market, which they were never to win back. Wines from Chile, South Africa and California poured into the breach created by cruise missiles.