The Dangerous Joy of Dr. Sex and Other True Stories (8 page)

Read The Dangerous Joy of Dr. Sex and Other True Stories Online

Authors: Pagan Kennedy

I had expected chrome and flashy mirrors, a downtown location, maybe an underground parking garage with spaces reserved for the coaches. After all, the Anderson-Cohen gym sent more Olympic

weightlifters to the 2000 games than did the official Olympic facility in Colorado. But the gym is unpretentious. It hunkers at the end of an access road that I had trouble finding on the map. The athletes park on the grass.

As soon as I swing open the door, the din hits me, the THUNK-thunk-thunk of barbells falling from six or seven feet in the air and then bouncing across the plywood platforms. Lifters sprawl on plastic chairs, waiting their turnâgawky kids training for basketball teams, tattooed guys, women who could pass for action figures, heavy kids who could pass for bookworms.

I find coach Cohen squatting under a barbell. When I get him in a chair, he's still squatting, elbows balanced on knees, as if he's ready to pounce, a man made entirely out of fast-twitch muscles.

Cheryl, he says, just returned from the Junior Championships, where she successfully defended her title as strongest under-20-year-old girl in the world. She needs rest. But in a few weeks, “we will bust her behind. She'll be here all day.”

What about the Haworth family? I ask. How does he think the parents managed to raise three such confident young women?

Cohen doesn't seem to be interested in that question. What interests him is that each of the Haworth girls fall into a different

weight class. “You've got Beth who weighs 130, 125 pounds. You've got Katie who weighs 170 and you've got Cheryl who weighs over 300.”

Just then, two of the three Haworth weight classes appearâCheryl and Katie. They announce their mission for the afternoon: ear-wax candles. Supposedly, you can stick one of these folk remedies into your ear, light it, and it will suck all the gunk out. They plan to find out if this is true.

But first, the girls take over the gym office. Katie swivels back and forth in the chair behind the desk, answering the Anderson-Cohen phone when it rings. I pull out my tape recorder, intending to interview her about her future, but it's just too hot. Arrows of sun scorch the desk. Katie and I become absorbed in winding weightlifting tape around the office pens. Days later, when I have returned home, I will find one of these swaddled pens in my bag.

Cheryl's cell phone bleeps. It's Ethan. Hand it over, I tell her, because I realize that a certain question has been gnawing at me. “Ethan,” I say, “What are you going to do after you become Pope? What's your plan for the church?”

He admits he doesn't have one. Cheryl grabs the phone away. “You don't have a plan? Ethan, you've got to have a plan!”

When we head over to the house she wants to buy, two real estate agents perch on a sofa. Cheryl sprawls on the floor. The sweet little two-bedroom ranch with a grill on the back porch requires a down-payment that's a bit beyond her means. Now Cheryl pitches mortgage terms at the agents. They treat her with the deference due a celebrity who may be trading up to a four-bedroom-with-swimming-pool in a few years.

“I don't think about it at all,” Cheryl told me earlier, about body size. However, if she follows her agent's advice, she will have to. He wants her to cash in on her body's power to explode assumptions about female strength, and the challenge she poses, willingly or not, to one-size-fits-all culture. It's not the easiest route to fame, but it sounds like a plan.

Â

Â

Â

Â

UPDATE:

At the 2004 Athens Olympics, Cheryl Haworth tore a ligament in her elbow. Once the favorite for a Gold, she came in sixth. Two years later, she was arrested for drunk driving. After an argument with her coach Mike Cohen, she decided to leave his gym. She sold her house and moved to a dorm in the Olympic training center in Colorado. I have no idea what happened to Ethan.

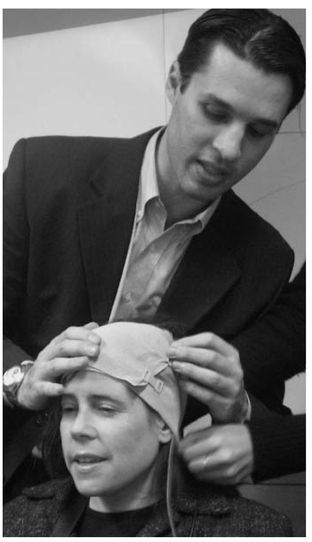

This spring, Stuart Gromley hunched over a desk in his bedroom, groping along the skin of his own forehead, trying to figure out where to glue the electrodes. The wires from those electrodes led to a Radio Shack Electronics Learning Lab, a toy covered with knobs, switches and meters. “For ages 10 and up,” the instructions on the box recommended. Gromley, a 39-year-old network administrator in San Francisco, had bought a kiddie lab because it had been decades since he'd last tinkered with electricity; he hoped its instruction sheets would help him cheat his way through the experiment he was about to set up. He couldn't afford to make mistakes. He was about to send the current from a 9-volt battery into his own brain.

His homemade machine was modeled on the devices used in some of the top research centers around the world. Called transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), the technology works on the principle that even the weak electrical signals generated by a small battery can penetrate the skull and affect hot-button areas on the outer surface of the brain. In the past few years, research papers have touted tDCS as a non-invasive and safe way to rejigger our thoughts and feelings, and possibly to treat a variety of mental disorders. Most provocatively, researchers at the National Institutes

of Health have shown that running a small jolt of electricity through the forehead can enhance the verbal abilities of healthy people. That is, tDCS might do more than just alleviate symptoms of disease. It might help make its users a little bit smarter.

Say “electricity” and “brain” in the same sentence, and most of us flash on certain scenes from

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

But tDCS has little in common with shock therapy. The amount of current that a 9-volt battery can produce is tiny, and most of it gets blocked by the skull anyway; what little current does go into brain tissue tends to stay close to the electrodes. By placing these electrodes on the forehead or the side of the head, researchers can pinpoint specific regions of the brain that they'd like to amp up or damp down.

Some researchers believe that if tDCS continues to pan out, a consumer version of the machine might someday appear on the market. The final product might look like an iPod attached to a hat with electrodes in its brimâavailable with a prescription from a doctor. Still, it's very simplicity might prove its undoing. How would a medical-supplies company make money off of a gizmo so rudimentary that it sounds like a 7th-grade science fair project? The cost of partsâelectrodes, a battery, a resistorâcould be as low as $10.

In fact, a small clique of hobbyists on the Web have already begun to discuss how to make the machines at home and where to put the electrodes. Like ham radio operators of the brain, they share advice with their fellow tinkerers. “I accidentally found a way to make GREY FLASHES IN MY VISION using a 9v battery. Don't you try it,” says one hacker in an online forum. “Here's how not to do it,” he adds, and then provides instructions.

Gromley is one such hobbyist. He says that the first time he read about tDCS machines, he immediately decided, “I'm going to build one of these.” He'd been suffering from bouts of depression since he was a teenager; antidepressant medication only made him feel worse; now, he hankered to find out if tDCS might give some relief. And he was curious about a technology that might let him fiddle with the knobs of his own personality, to experience something that might alter his consciousness. “I'm always thinking, âWhat would it be like to be another person?'”

And so he set up the Radio Shack kit on a paint-splattered TV trayâthe “art space” in his bedroom. He had bought sponge electrodes off of eBay, and he made an educated guess about how to position the electrodesâone on a temple area and one on the browâbased on the medical studies he'd pored over. When he

flipped on a switch, current ran from the battery through a resistor and then into wires and into his prefrontal cortex. He leaned back in his chair with his eyes closed, wondering if he felt anything. That's when he saw the flashâwhat he describes as a “horizontal lightning bolt”âthat seemed to arc from one side of his forehead to the other.

“No, that didn't happen,” he thought to himself, and tried to calm himself. Then, a few minutes later, he shifted in his seat, the wires jiggled, and he saw lightning again. Gromley yanked off the electrodes. He began searching on Google, using keywords like “tDCS” and “flash” until he found a study that reassured him: those spots of light were harmless.

So Gromley went back to his experiment. Flash, flash, flash. He rearranged the electrodes several times before he found the sweet spot.

“Do you remember the first time you drank coffee? It was like, âOh my god, if I'd known how good this was, I'd be drinking coffee all the time.' Well, [tDCS] wasn't exactly like the first cup of coffee,” Gromley says. “It was more like a cup you might have in the first month of drinking coffee. It's like, âHmm, I don't feel bad. I feel alert. I feel up.'” Actual coffee had long ago ceased to pull

Gromley out of his depression, but now he had the electronic kind. He used the machine about once a day for a month, and then he found that he no longer needed it much. Lately, he's been spending long hours at workâtoo busy to be depressed.

Of course, one man's Radio Shack adventure does not a study make, and the effects that Gromley felt could as easily be attributed to the placebo effect as to a tickle of electricity. Needless to say, the researchers I talked to cautioned against trying this sort of thing at home, although they had a grudging respect for anyone with the pluck to do it. “In the past, a lot of scientific discoveries were made by amateurs who experimented on themselves,” according to Peter Bulow, a psychiatrist at Columbia University. He said that a recent safety study found that tDCS causes no damage to brain tissue, but cautioned that any cutting-edge treatment comes with unknown risks. Bulow himself has just submitted a proposal to study the effects of tDCS on 20 depressed patients.

He's in good company. Teams of researchers are experimenting with battery-powered electrodes at the National Institutes of Health, the Harvard Center for Noninvasive Brain Stimulation, and at the University of Göttingen in Germany, among other centers. They're exploring tDCS as a treatment for depression,

chronic pain, addiction to cigarettes, Parkinson's disease, as well as motor disorders caused by stroke and neurodegenerative diseases. The gizmo, still only a few years old in its present incarnation, has become the Ronco Brain-O-Matic of the research world: a device that promises endless uses. But it remains to be seen whether it will prove itself as a truly effective therapy for any one disease.

In 1962, a 30-year-old woman shuffled around a hospital in England with a battery pinned to her dress. Two silver electrodes, wrapped in gauze, winked above her brow, like a second set of eyes. She'd spent half her life in mental asylums: when she was a girl, her father had shot himself, and afterward she'd become convinced that other people could see a mark upon her. Nothing had lifted her malaise: not even shock treatment. When she arrived at Summersdale Hospital, she muttered “Get rid of me” in response to questions. Researchers (J.W.T Redfearn and O.C.J. Lippold) attached the two positively charged electrodes to her forehead, with the cathode on her knee, to see whether they could use battery power to ease her out of her depression. They kept her brow area bathed in electricity for as many as eleven hours a

day, three treatments a week. She began to sleep soundly, no longer tormented by nightmares; she ate well; she prettied herself up; she found a boyfriend. She became, the researchers said, a “different person.”

That year, she was just one of several dozen people wandering the halls of Summersdale Hospital with electrodes plastered to their foreheads and batteries on their lapels like boutonnieres. In an earlier study, Lippold and Redfearn had found that they could change the personalities of their subjects with electrical stimulation: positively charged electrodes on the forehead caused people to giggle and chat. Under the influence of negatively charged electrodes, people shut down, became silent and apathetic. Some of the patients had so enjoyed the positive electrodes that they asked for the “battery treatment” again. And so Lippold and Redfearn launched this new study; this time they would expose peopleâmany of them severely depressedâto long sessions of electrical stimulation. The patients were allowed to go home with electrodes glued to their heads, the battery still buzzing. Almost half of them experienced miraculous recoveries. A shell-shocked World War II veteran compared the effects to a snoot of a whiskeyâ“I feel quite all right,” he crowed, after he'd been stimulated.

In the decade that followed, other researchers tried to replicate these effects. They produced inconsistent results. Nowadays it's clear why: researchers applied currents that were too small and glued electrodes to the wrong parts of the scalp. “They used some parameters of stimulation that we know now are not effective. They didn't have the information that we have now,” according to Felipe Fregni, an instructor in Neurology at Harvard Medical School. Because the battery-powered electrodes seemed to be unreliable, the medical community lost interest in brain polarization.

Then, in the 1980s, researchers found a much more powerful way to stimulate isolated buttons of the brain. Called repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), the technique uses electromagnetic radiationâwhich can easily pass through the skullâto create localized electrical fields near the surface of the brain. The effects of rTMS are dramatic and reproducible. Place the machine's wand on one part of the scalp and the patient will lose her ability to talk; move the wand to another spot and her leg will jerk.

In essence, rTMS is a souped-up version of the old battery-and-electrodes treatment. But it also comes with greater risks: it can trigger seizures, an arm that won't stop shaking or a patient who

slumps over in his chair. However, such side effects are rare, and rTMS has proven to be a powerful tool for mapping the brain and modulating brain activity; in the 1990s, researchers began using it (along with other new technologies) to draw blueprints of neural function. This new knowledge, in turn, meant that the battery treatment became relevant againâbecause now scientists could design a more effective tDCS machine. In the late 1990s, a team at the University of Göttingen enlarged the electrodes and covered them in sponges in order to allow more current to pass through the skull. They also created new protocols for placement of the electrodes, aiming them with greater accuracy at hotspots such as the motor cortex. Just a few years ago, these design changes began to pay off in studies that showed promising results: the new, improved battery treatment could quicken the tongue and the hand. It could make people smarter and faster, if only by a small margin. When German researchers trained the positive electrode on the motor cortex, their human subjects became significantly faster at learning to hit a keyboard in response to a visual cue.

Other researchers confirmed this provocative finding: brain stimulation could enhance performance in healthy people. For instance, a 2005 study from the National Institute of Neurological

Disorders and Stroke (NINDS, an affiliate of NIH) found that tDCS stimulation revved up people's verbal abilities. They were able to generate longer lists of words starting with, for instance, F or W within a time limit. This has implications for victims of stroke and other neurodegenerative conditionsâif tDCS can enhance the performance of healthy people, perhaps a machine could help pull lost words and hand movements out of damaged brains. For some patients, a wearable brain machine represents one of the few, dim hopes for recovery.