The CV (2 page)

Authors: Alan Sugar

1990 – 1999:

Gained experience in the world of professional football, high level litigation, speaking events at the Oxford Union, Cambridge Union and other universities and schools, as well as to the business community. Was responsible for exposing corruption in the football industry and was engaged to write for several national newspapers on various topics.

1991 – Rescued Tottenham Hotspur Football Club to avoid bankruptcy.

1993 – Engaged in high profile court action where football corruption was core to the proceedings. Introduced the phrases ‘bung’ and ‘Carlos Kickaball’ into common usage in respect of football corruption and the influx of foreign players.

See here.1994 – Acquired Viglen Computers Ltd, suppliers to schools and universities as well as to government departments.

1995 – Acquired Dancall Radio, a mobile phone manufacturer in Denmark for £6m, and made further investment of £10m for new designs, plant and equipment.

1996 – Launched the first dual-band mobile phone at Hanover Fair to the amazement of the then market leaders Ericsson and Nokia.

1996 – Involved in litigation against American Hard Disc Drive manufacturers to recover damages suffered by Amstrad due to defective drives.

1997 – On my 50th birthday (24th March), sold Dancall to Bosch Germany for US$150m, Dancall having been purchased just 2 years before at £6m.

1997 – Amstrad Plc, by way of a Scheme of Arrangement, was broken up with substantiation amount of cash returned to shareholders, and new shares issued to shareholders in ex-subsidiaries Viglen Plc and Betacom Plc (which changed its name to Amstrad) as well as entitlement to any proceeds of litigation with the Hard Disc Drive manufacturers.

1998 – At the request of Gordon Brown, the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, embarked on series of visits to schools and universities to conduct Q&A sessions on enterprise.

1999 – Victory decision in the High Court with US$150m damages awarded to Amstrad from the Hard Disc Drive manufacturers.

1999 – Invited to tea at The White House by US President Bill Clinton and the First Lady.

2000 – 2009:

Gained experience in participating in television programmes, further engagement in writing for newspapers including own column in the Daily Mirror. Continued visits and Q&A sessions on enterprise.

2000 – Was honoured by her Majesty the Queen with a Knighthood.

2001 – Sold part of my interest in Tottenham Hotspur FC and resigned from the Board as Chairman and Director.

2005 – Appeared in the first series of ‘The Apprentice’ and won BAFTA award.

See here.2005 – Honoured by Brunel University as a Doctor of Science.

2006 – ‘The Apprentice’ won most of the awards granted to TV shows (except ITV national TV awards – no surprise as ‘The Apprentice’ is a BBC show).

2007 – Sold Amstrad Plc (formerly Betacom) to BSkyB for £135m.

2008 – Appointed to Government Business Council by Prime Minister Gordon Brown.

2009 – Led government’s Apprenticeship advertising campaign and four roadshow seminars.

2009 – Appointed by Prime Minister Gordon Brown as Enterprise Champion to advise government on small business and enterprise.

2009 – On 20th July, took my seat in the House of Lords as Alan Baron Sugar of Clapton in the London Borough of Hackney.

See here.

© Lord Sugar, July 2009

Not for reproduction in full or part form without prior written consent

[email protected]

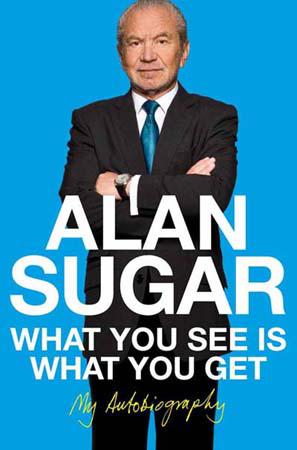

These extracts are taken from Alan Sugar’s autobiography,

What You See is What you Get.

The ebook is available from the

Kindle Store

,

Waterstones.com

and the

iBookstore

.

1957 – 1958: Enterprise activities

I had loads of enterprises on the go. Next to Woolmer House there was a rag-and-bone merchant who would go round collecting items such as old iron and other metal, clothing and material. He’d pay scrap value for the stuff. In his yard was a sign saying, ‘Wool 5s per lb [five shillings per pound of weight], cotton 1s 6d per pound [one shilling and sixpence], brass and copper 2d per pound [tuppence].’ Playing out in the street when I was eleven, I noticed people taking items in and getting money in exchange and I wondered if I could get hold of any stuff, so that I too could make some money. It was during one of my other ventures – car-cleaning – that I found something.

In the back streets of Clapton, some of the big Victorian houses were converted into small garment factories with rooms full of machinists. These factories would sub-contract for bigger manufacturers using ‘outdoor workers’ (the old name for sub-contractors). One day, while cleaning the factory boss’s car, I saw in the front garden some open sacks of material trimmings, ready for the dustman to take away. When I went inside to collect my 1s 6d, I asked the boss what was in these sacks and he explained they were remnants of the material used to make the clothes. I asked him if I could take some and he said I could, but looked puzzled.

‘What are you going to do with them?’ he asked.

‘Don’t worry, leave it to me,’ I replied. The sacks were bigger than I was, so I went back to the flats and borrowed a pram. I loaded on two sacks and took them round to the rag-and-bone man.

Here was my first experience of getting ‘legged over’. Unbeknown to me, the sacks contained gold dust as far as the scrap merchant was concerned, as the material was wool. This bloke took one look at this eleven-year-old and said, ‘What you’ve got in those sacks is rubbish.’ He weighed the stuff on his

scales and said, ‘I’ll give you half a crown [2s 6d] for the lot.’ I took it. Naïve – stupid, you might say – but half a crown was a lot of money in those days.

The next week, after cleaning the boss’s car, I asked him what kind of material was in those sacks. When he told me it was wool, I was furious – I should have got at least £1 10s for two sacks of wool. I took a scrap of the material to the rag-and-bone man and confronted him. ‘I’ve just been told this is wool – you told me it was rubbish. I want some more money or I want the two sacks back,’ I yelled at him angrily. I won’t tell you what he said to me. He slung two shillings at me and told me to clear off.

‘I can get loads more of this stuff and I’m going to find another rag-and-bone man to sell it to!’

He just laughed and virtually threw me out.

Another side of me came out now. I was wound up and angry. I wasn’t frightened to speak up, but short of grabbing hold of him or kicking him, what could I do? He was a grown man and I was an eleven-year-old shnip. I went back home and told my mum and dad what had happened. They laughed, then my father asked, ‘How much did you get in the end?’

‘Four and six.’ A sudden look of fear came over his face at the realisation that his eleven-year-old son had made 4s 6d.

‘Where did you get this stuff from?’ he said.

‘I told you – from the factory down the road.’

‘They let you take it? You sure you didn’t take it without asking?’

‘No. The boss gave it to me. He wanted to get rid of it. Normally the dustman takes it away.’

‘Are you sure?’

I couldn’t believe it. Instead of being complimented, I was being interrogated as if I’d done something wrong! It was a strange attitude, but one I’d become increasingly familiar with in later years. Many’s the time I’d have to play down the success of my business activities because my father could not believe that someone so young could make so much money. To put things into perspective, his take-home pay at the time was £8 for working a forty-hour week. How could an eleven-year-old boy go out and make 4s 6d in just a couple of hours? Basically, I’d spotted some stuff in one place and seen another place to sell it. And what’s more, I really enjoyed doing it.

1959 – 1963: Enterprise activities

While my social life was non-existent, I still kept busy with work and my hobbies. Sometimes they combined, as with the Saturday job I took in a chemist’s in Walthamstow High Street market. Having found that I enjoyed science and engineering at school (in contrast to some of the more boring subjects such as history and the arts), I thought pharmacy might be the way to go, and naïvely I figured I would learn about it on the job. The shop was owned by a very nice man called Michael Allen. When I told him I aspired to be a pharmacist, he taught me as much as he possibly could about drugs and that sort of stuff.

I spent most of my time in the front of the shop selling cough syrups and lozenges. Here I was, a young kid, being asked by punters what cough syrup they should take. Mr Allen taught me to ask if it was a chesty cough or a dry cough. For chesty, you got a bottle of Benylin; for dry, you got a bottle of Pholcodine Linctus.

Mr Allen was a bit of a boffin who knew all the technical pharmaceutical stuff, but in my opinion lacked a bit of business savvy. I introduced one of my marketing ideas to him and his staff. When asked by the customer for a bottle of, say, Milk of Magnesia, if you were to reply, ‘Small or large?’ most punters would say, ‘Small.’ Much better to ask, ‘Do you want the small 1s 6d one or the extra-value 2s 6d one?’ I applied this to lots of things in the shop, ranging from Old Spice aftershave to cough syrup, and it worked nine times out of ten.

There were exceptions to this rule. Packets of Durex, for example, came in both economy and bulk packs, but I wasn’t going to ask a strapping six-foot-tall punter if he wanted the small pack – it could have been taken the wrong way.

Now, here’s a bit of trivia you may find as surprising as I did: a large

number of married women would buy contraceptives as part of their weekly shop, on behalf of their lazy husbands. At first, as a young lad of fifteen, I was a bit embarrassed when a woman asked me for them, but after a while it was like water off a duck’s back. However, when it came to Tampax or sanitary towels, I certainly wasn’t going to try my ‘small or extra-value’ scam. Instead, it was a case of: ‘They’re over there, madam, help yourself.’ That was where I drew the line. After all, there was a limit on how far you’d go for the boss!

It was at Mr Allen’s shop that I also developed my interest in photography, which was sparked by the cameras, film and developing paper he sold. I couldn’t afford a good camera, but I soon picked up tips on which model was the most economic to buy. This information was going to be useful because another sideline I had in mind was to become a photographer. While I scraped together the money to buy a Halina camera, I was already working out what to say to my parents. I had visions of my father shaking his head in disapproval when I brought it home. ‘Another waste of money,’ he’d say, while my mother would shrug her shoulders and ask, ‘How much was that?’ All this despite the fact that I was paying for it myself!

It

was

difficult for me to justify laying out £12 for a camera when the old man got £8 for doing a week’s work, so I tried to save his pride with answers such as, ‘I’m paying off for it to Mr Allen,’ which, to be fair, I did do when it came to my next camera – the Yashica, a poor man’s Rolleifiex.

Not only did I buy the camera, but I also invested in an enlarger, a lens and developing equipment. Mum and Dad couldn’t understand how I’d managed to buy them and the situation wasn’t helped by my brother-in-law, Harold Regal, who said, ‘This is very expensive stuff, Alan. How have you managed to afford all this?’ I didn’t need him winding the old man up.

My father was such a worrier. I swear he thought that one day there’d be a policeman knocking at our door – I don’t know why. He just couldn’t accept what this young lad was up to. My only criticism of him would be that he didn’t support me in any of these activities and always seemed to think there was something wrong. I wouldn’t say the same about my mother though; she was quite supportive.