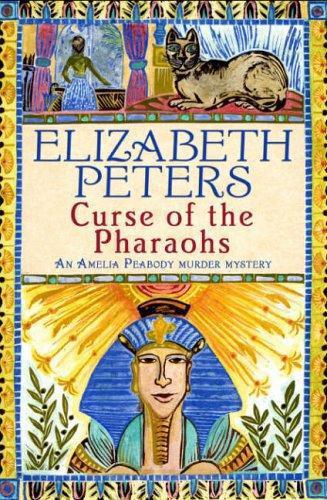

The Curse of the Pharaohs

Read The Curse of the Pharaohs Online

Authors: Elizabeth Peters

Tags: #Mystery & Detective, #Mystery, #Peabody, #Fiction, #Egypt, #Amelia (Fictitious character), #Women Sleuths, #Historical, #Women archaeologists, #Crime & mystery, #Archaeologists? spouses

THE CURSE OF THE PHARAOHS

Elizabeth Peters

Book 2

Amelia Peabody

One

THE events I am about to relate began on a December afternoon, when I had invited Lady Harold Carrington and certain of her friends to tea.

Do not, gentle reader, be misled by this introductory statement. It is accurate (as my statements always are); but if you expect the tale that follows to be one of pastoral domesticity, enlivened only by gossip about the county gentry, you will be sadly mistaken. Bucolic peace is not my ambience, and the giving of tea parties is by no means my favorite amusement. In fact, I would prefer to be pursued across the desert by a band of savage Dervishes brandishing spears and howling for my blood. I would rather be chased up a tree by a mad dog, or face a mummy risen from its grave. I would rather be threatened by knives, pistols, poisonous snakes, and the curse of a long-dead king.

Lest I be accused of exaggeration, let me point out that I have had all those experiences, save one. However, Emerson once remarked that if I

should

encounter a band of Dervishes, five minutes of my nagging would unquestionably inspire even the mildest of them to massacre me.

Emerson considers this sort of remark humorous. Five years of marriage have taught me that even if one is unamused by the (presumed) wit of one's spouse, one does not say so. Some concessions to temperament are necessary if the marital state is to flourish. And I must confess that in most respects the state agrees with me. Emerson is a remarkable person, considering that he is a man. Which is not saying a great deal.

The state of wedlock has its disadvantages, however, and an accumulation of these, together with certain other factors, added to my restlessness on the afternoon of the tea party. The weather was dreadful—dreary and drizzling, with occasional intervals of sleety snow. I had not been able to go out for my customary five-mile walk; the dogs

had

been out, and had returned coated with mud, which they promptly transferred to the drawing-room rug; and Ramses...

But I will come to the subject of Ramses at the proper time.

Though we had lived in Kent for five years, I had never entertained my neighbors to tea. None of them has the faintest idea of decent conversation. They cannot tell a Kamares pot from a piece of prehistoric painted ware, and they have no idea who Seti the First was. On this occasion, however, I was forced into an exercise of civility which I would ordinarily abhor. Emerson had designs on a barrow on the property of Sir Harold, and—as he elegantly expressed it—it was necessary for us to "butter up" Sir Harold before asking permission to excavate.

It was Emerson's own fault that Sir Harold required buttering. I share my husband's views on the idiocy of fox hunting, and I do not blame him for personally escorting the fox off the field when it was about to be trapped, or run to earth, or whatever the phrase may be. I blame Emerson for pulling Sir Harold out of his saddle and thrashing him with his own riding crop. A brief, forceful lecture, together with the removal of the fox, would have gotten the point across. The thrashing was superfluous.

Initially Sir Harold had threatened to take Emerson to law. He was prevented by some notion that this would be unsportsmanlike. (Seemingly no such stigma applied to the pursuit of a single fox by a troop of men on horseback and a pack of dogs.) He was restrained from physically attacking

Emerson by Emerson's size and reputation (not undeserved) for bellicosity. Therefore he had contented himself with cutting Emerson dead whenever they chanced to meet. Emerson never noticed when he was being cut dead, so matters had progressed peacefully enough until my husband got the notion of excavating Sir Harold's barrow.

It was quite a nice barrow, as barrows go—a hundred feet long and some thirty wide. These monuments are the tombs of antique Viking warriors, and Emerson hoped to discover the burial regalia of a chieftain, with perhaps evidences of barbaric sacrifice. Since I am above all things a fair-minded person, I will candidly confess that it was, in part, my own eagerness to rip into the barrow that prompted me to be civil to Lady Harold. But I was also moved by concern for Emerson.

He was bored. Oh, he tried to hide it! As I have said, and will continue to say, Emerson has his faults, but unfair recrimination is not one of them. He did not blame

me

for the tragedy that had ruined his life.

When I first met him, he was carrying on archaeological excavations in Egypt. Some unimaginative people might not consider this occupation pleasurable. Disease, extreme heat, inadequate or nonexistent sanitary conditions, and a quite excessive amount of sand do mar to some extent the joys of discovering the treasures of a vanished civilization. However, Emerson adored the life, and so did I, after we joined forces, maritally, professionally, and financially. Even after our son was born we managed to get in one long season at Sakkara. We returned to England that spring with every intention of going out again the following autumn. Then our doom came upon us, as the Lady of Shalott might have said (indeed, I believe she actually did say so) in the form of our son, "Ramses" Walter Peabody Emerson.

I promised that I would return to the subject of Ramses. He cannot be dismissed in a few lines.

The child had been barely three months old when we left him for the winter with my dear friend Evelyn, who had married Emerson's younger brother Walter. From her grandfather, the irascible old Duke of Chalfont, Evelyn had inherited Chalfont Castle, and a great deal of money. Her husband—one of the few men whose company I can tolerate for more than an hour at a time—was a distinguished Egyptologist in his own right. Unlike Emerson, who prefers excavation, Walter is a philologist, specializing in the decipherment of the varied forms of the ancient Egyptian language. He had happily settled down with his beautiful wife at her family home, spending his days reading crabbed, crumbling texts and his evenings playing with his ever-increasing family.

Evelyn, who is the dearest girl, was delighted to take Ramses for the winter. Nature had just interfered with her hopes of becoming a mother for the fourth time, so a new baby was quite to her taste. At three months Ramses was personable enough, with a mop of dark hair, wide blue eyes, and a nose which even then showed signs of developing from an infantile button into a feature of character. He slept a great deal. (As Emerson said later, he was probably saving his strength.)

I left the child more reluctantly than I had expected would be the case, but after all he had not been around long enough to make much of an impression, and I was particularly looking forward to the dig at Sakkara. It was a most productive season, and I will candidly admit that the thought of my abandoned child seldom passed through my mind. Yet as we prepared to return to England the following spring, I found myself rather looking forward to seeing him again, and I fancied Emerson felt the same; we went straight to Chalfont Castle from Dover, without stopping over in London.

How well I remember that day! April in England, the most delightful of seasons! For once it was not raining. The hoary old castle, splashed with the fresh new green of Virginia creeper and ivy, sat in its beautifully tended grounds like a gracious dowager basking in the sunlight. As our carriage came to a stop the doors opened and Evelyn ran out, her arms extended. Walter was close behind; he wrung his brother's hand and then crushed me in a fraternal embrace. After the first greetings had been exchanged, Evelyn said, "But of course, you will want to see young Walter."

"If it is not inconvenient," I said.

Evelyn laughed and squeezed my hand. "Amelia, don't pretend with me. I know you too well. You are dying to see your baby."

Chalfont Castle is a large establishment. Though extensively modernized, its walls are ancient and fully six feet thick. Sound does not readily travel through such a medium, but as we proceeded along the upper corridor of the south wing, I began to hear a strange noise, a kind of roaring. Muted as it was, it conveyed a quality of ferocity that made me ask, "Evelyn, have you taken to keeping a menagerie?"

"One might call it that," Evelyn said, her voice choked with laughter.

The sound increased in volume as we went on. We stopped before a closed door. Evelyn opened it; the sound burst forth in all its fury. I actually fell back a pace, stepping heavily on the instep of my husband, who was immediately behind me.

The room was a day nursery, fitted up with all the comfort wealth and tender love can provide. Long windows flooded the chamber with light; a bright fire, guarded by a fender and screen, mitigated the cold of the old stone walls. These had been covered by paneling hung with pretty pictures and draped with bright fabric. On the floor was a thick carpet strewn with toys of all kinds. Before the fire, rocking placidly, sat the very picture of a sweet old nanny, her cap and apron snowy white, her rosy face calm, her hands busy with her knitting. Around the walls, in various postures of defense, were three children. Though they had grown considerably, I recognized these as the offspring of Evelyn and Walter. Sitting bolt upright in the center of the floor was a baby.

It was impossible to make out his features. All one could see was a great wide cavern of a mouth, framed in black hair. However, I had no doubt as to his identity.

"There he is," Evelyn shouted, over the bellowing of this infantile volcano. "Only see how he has grown!"

Emerson gasped. "What the devil is the matter with him?"

Hearing—how, I cannot imagine—a new voice, the infant stopped shrieking. The cessation of sound was so abrupt it left the ears ringing.

"Nothing," Evelyn said calmly. "He is cutting teeth, and is sometimes a little cross."

"Cross?" Emerson repeated incredulously.

I stepped into the room, followed by the others. The child stared at us. It sat foursquare on its bottom, its legs extended before it, and I was struck at once by its shape, which was virtually rectangular. Most babies, I had observed, tend to be spherical. This one had wide shoulders and a straight spine, no visible neck, and a face whose angularity not even baby fat could disguise. The eyes were not the pale ambiguous blue of a normal infant's, but a dark, intense sapphire; they met mine with an almost adult calculation.

Emerson had begun circling cautiously to the left, rather as one approaches a growling dog. The child's eyes swiveled suddenly in his direction. Emerson stopped. His face took on an imbecilic simper. He squatted. "Baby," he crooned. "Wawa. Papa's widdle Wawa. Come to nice papa."

"For God's sake, Emerson!" I exclaimed.

The baby's intense blue eyes turned to me. "I am your mother, Walter," I said, speaking slowly and distinctly. "Your mama. I don't suppose you can say Mama."

Without warning the child toppled forward. Emerson let out a cry of alarm, but his concern was unnecessary; the infant deftly got its four limbs under it and began crawling at an incredible speed, straight to me. It came to a stop at my feet, rocked back onto its haunches, and lifted its arms.

"Mama," it said. Its ample mouth split into a smile that produced dimples in both cheeks and displayed three small white teeth. "Mama. Up. Up, up, up, UP!"

Its voice rose in volume; the final UP made the windows rattle. I stooped hastily and seized the creature. It was surprisingly heavy. It flung its arms around my neck and buried its face against my shoulder. "Mama," it said, in a muffled voice.

For some reason, probably because the child's grip was so tight, I was unable to speak for a few moments.

"He is very precocious," Evelyn said, as proudly as if the child had been her own. "Most children don't speak properly until they are a year old, but this young man already has quite a vocabulary. I have shown him your photographs every day and told him whom they represented."

Emerson stood by me staring, with a singularly hangdog look. The infant released its stranglehold, glanced at its father, and—with what I can only regard, in the light of later experience, as cold-blooded calculation—tore itself from my arms and launched itself through the air toward my husband.

"Papa," it said.

Emerson caught it. For a moment they regarded one another with virtually identical foolish grins. Then he flung it into the air. It shrieked with delight, so he tossed it up again. Evelyn remonstrated as, in the exuberance of its father's greeting, the child's head grazed the ceiling. I said nothing. I knew, with a strange sense of foreboding, that a war had begun—a lifelong battle, in which I was doomed to be the loser.

It was Emerson who gave the baby its nickname. He said that in its belligerent appearance and imperious disposition it strongly resembled the Egyptian pharaoh, the second of that name, who had scattered enormous statues of himself all along the Nile. I had to admit the resemblance. Certainly the child was not at all like its namesake, Emerson's brother, who is a gentle, soft-spoken man.

Though Evelyn and Walter both pressed us to stay with them, we decided to take a house of our own for the summer. It was apparent that the younger Emersons' children went in terror of their cousin. They were no match for the tempestuous temper and violent demonstrations of affection to which Ramses was prone. As we discovered, he was extremely intelligent. His physical abilities matched his mental powers. He could crawl at an astonishing speed at eight months. When, at ten months, he decided to learn to walk, he was unsteady on his feet for a few days; and at one time he had bruises on the end of his nose, his forehead, and his chin, for Ramses did nothing by halves—he fell and rose to fall again. He soon mastered the skill, however, and after that he was never still except when someone was holding him. By this time he was talking quite fluently, except for an annoying tendency to lisp, which I attributed to the unusual size of his front teeth, an inheritance from his father. He inherited from the same source a quality which I hesitate to characterize, there being no word in the English language strong enough to do it justice. "Bullheaded" is short of the mark by quite a distance.

Emerson was, from the first, quite besotted with the creature. He took it for long walks and read to it by the hour, not only from

Peter Rabbit

and other childhood tales, but from excavation reports and his own

History of Ancient Egypt,

which he was composing. To see Ramses, at fourteen months, wrinkling his brows over a sentence like "The theology of the Egyptians was a compound of fetishism, totem-ism and syncretism" was a sight as terrifying as it was comical. Even more terrifying was the occasional thoughtful nod the child would give.