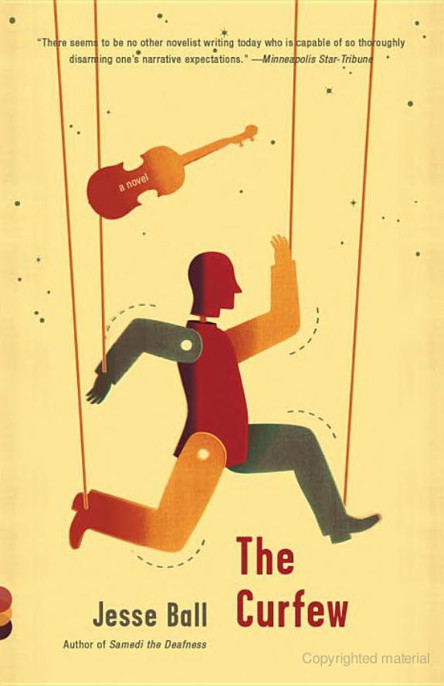

The Curfew

Authors: Jesse Ball

Jesse Ball

THE CURFEW

Jesse Ball (1978–) is a poet and novelist. His novels include

The Way Through Doors

(2009) and

Samedi the Deafness

(2007), which was a finalist for the Believer Book Award. He has published books of poetry and prose:

The Village on Horseback

(2010),

Vera & Linus

(2006), and

March Book

(2004). A book of his drawings,

Og svo kom nottin

, appeared in Iceland in 2006. He won the

Paris Review

’s Plimpton Prize in 2008 for

The Early Deaths of Lubeck, Brennan, Harp & Carr

. His poetry has appeared in the Best American Poetry series. He is an assistant professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and teaches classes on lying, lucid dreaming, and general practice.

ALSO BY JESSE BALL

The Way Through Doors

Samedi the Deafness

A V

INTAGE

C

ONTEMPORARIES

O

RIGINAL

, J

UNE 2011

Copyright © 2011 by Jesse Ball

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage Contemporaries and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ball, Jesse, 1978–

The curfew : a novel / by Jesse Ball.

p. cm.

“A Vintage Contemporaries Original.”

eISBN: 978-0-307-74320-6

1. Fathers and daughters—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3602.A596C87 2011

813′.6—dc22

2011001509

Cover image: Andy Baker/Ikon Images/Getty Images

Cover design by Cardon Webb

v3.1

For Alda Aegisdottir

We are born in this cemetery, but must not despair.

—Piet Soron, 1847

PART

1

There was a great deal of shouting and then a shot. The window was wide open, for the weather was often quite fine and delicate during late summers in the city of C. Yes, the window was wide open and so the noise of the shot was loud, almost as though it had been fired in the room itself, as though one of the two people in the room had decided to shoot a gun into the body of the other.

This was not the case, however. And because no one in the room itself had been shot, the man, William Drysdale, twenty-nine, once-violinist, at present, epitaphorist, and his daughter, Molly, eight, schoolchild, slept on.

Those were their methods of employment. Daily, Drysdale went about to appointments while Molly went to school and was told repeatedly to repeat things. She could not, and didn’t.

In the street beyond the window, it was very shady and pleasant. An old woman was bleeding, hunched over a bench. Two men were standing fifty feet away, one holding a gun. Some ten feet from the bench, a man was lying underneath the wheels of a truck, which seemed to have injured him, perhaps irreparably. The driver was kneeling and saying something. He stood up and waved to the two men. The one with the pistol was putting it away. Another, smaller truck arrived for the bodies. The man who had had the pistol, but no longer showed it—he was directing people to go away. People were going away.

One minute after the gunshot, the street was empty. This was often the case. I shall introduce this city to you as a city of empty streets—empty only when something occurred, momentarily empty and soon full again, but empty nonetheless.

I shall introduce this city and its occupants as a series of objects whose relationship cannot be told with any certainty. Though violence may connect them, though pity, compassion, hope may marry one thing to another, still all that is in process cannot be judged, and that which has passed has gone beyond judgment, which leaves us again, with lives and belongings, places, shuttling here and there, hapless, benighted, discordant.

It was a school day and so, after a while, the two in the room began to stir. Molly woke first, and dressed herself. She was an able child, although mute.

—We will get something on the way, said William.

Molly nodded to herself. She stood by her folding pallet in the corner of the room and held up before her the two dresses that were hers. One was blue and the other yellow. Which to wear?

And then they were in line at the bakery, and she had on the yellow, which matched her somewhat torn yellow dancing slippers, although she did not dance. She did not have a bag with books because it was not that sort of school.

—Two of those, said William. And one of those.

—Do you want one now? he asked.

Molly signed, *Not yet.

Well, what sort of school was it, then? It was one of the schools where you sat in rows on benches and the teachers told you what to think. You recited things and wrote things repeatedly. You read from books that were held on little chains to the tables. Examinations were given, and often sticks were employed to instill discipline. There was a little area of dirt where they could play at lunchtime. Play was encouraged, as was snitching.

*Here we are, said Molly.

—Goodbye! said William, and caught her up for a moment.

She ran inside the building. Other children pushed past him as he stood there watching after.

—Drysdale, did you hear?

A coarse man of advancing years was there with wife. One might confuse either for a banker.

—Latreau’s dead. Shot this morning.

—The old woman? For what?

—Pushed someone in front of a bus.

—I heard it was a truck, said the wife. She thought the man was a cop, so she pushed him in front of a truck. But they caught her before she could get away.

—I’m sorry to hear that, said William absently. I truly am.

His lips hardly moved.

William walked away without looking at either of them. He hadn’t looked at them once the whole time. If one had been watching, one might even have thought that the couple had just been speaking to each other. William was that cautious.

The town was called a town, but it was a city. This is a convention of the very largest cities. It had districts: old districts, new districts, poor districts, trading districts, guard districts. There had been a jail once, but now there was no need for a jail. The system was much too efficient for that. Punishments were either greater or they did not occur at all. An ordinary nation, full of ordinary citizens, their concerns, difficulties, cruelties, injustices, had gone to sleep one night and woken the next morning to find in the place of the old government an invisible state, with its own concerns, difficulties, cruelties, injustices. Everything was strictly controlled and maintained, so much so that it was possible, within certain bounds, to pretend that nothing had changed at all.

Who had overthrown it? Why? Such things weren’t clear at all, just as it wasn’t entirely clear that anything had been overthrown. It was as if a curtain had been drawn and one could see to that curtain but not beyond. One remembered that the world had been different, and not long ago. But how? This was the question that nagged at those who could not avoid asking questions.

The nothing that had changed at all was really beyond bearing. Houses and buildings were full of desperate people who deeply misunderstood their desperation. This was due to artful explanation on the part of the government. It is impossible to tell, many said out of the corners of their mouths, if the ministry is thinking well of us—if they are acting on our behalf. Yet still there were acorns falling from trees, fish breaking the surfaces of ponds, etc. In a long life, said many an old man, this is but one more thing. Yet there were others who were young and knew nothing about the helplessness of life’s condition. Did they glow with light? They did, but of course, it could not be seen. And all the while, the grinding of bones like machinery, and the light step of tightrope walkers out beyond the windows.

But recently, only recently, those who could not bear to be governed in this way had taken steps. It was impossible to say exactly what had altered, but clashes between the two sides were now common, and the people of the city had grown used to the finding of bodies without explanation.

Such explanations, of course, may only be offered later, when one side has won.