The Crystal City Under the Sea (5 page)

“Why are they always whispering in corners:hen?” retorted Félicie, somewhat softened.

“They are not whispering!” protested Mademoielle Luzan; “they are chatting confidentially.And what is there remarkable in

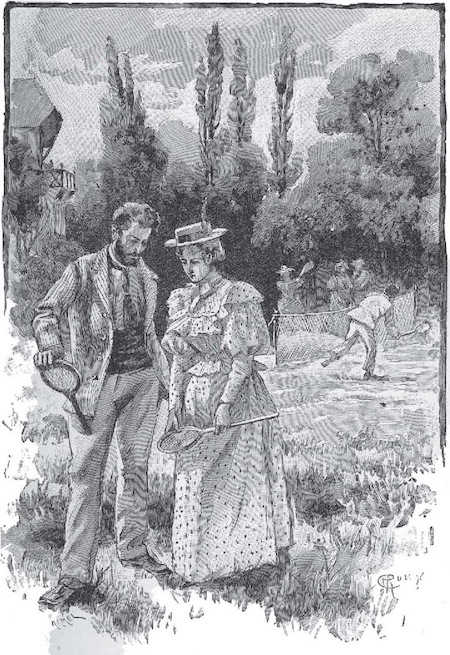

The cousins.

that? Do you not know that M. Caoudal has just narrowly escaped death? Wouldn’t you, if you were Hélène, be anxious to know every detail of his adventure?”

In reality, without any one being able to accuse them of whispering, as Félicie said, it was evident that Hélène and René had plenty to say to each other; and it was not, in truth, surprising that those who were not in their confidence should infer something strange. And how came it that Madame Caoudal, who had heard the whole story from him, and Stephen Patrice, who had heard it first, were neither of them recipients of these later confidences? Why was Madame Caoudal so radiant and Doctor Patrice so doleful? Was it that one of them saw the realization of her hopes, and the other, that which he had so long feared?

“This accident has touched their hearts and drawn them together,” said the good lady, “Sometimes good comes out of evil.”

“Undine will have to give way to Hélène,” thought the doctor, sighing. “Well, so much the better! It wouldn’t do to play the part of the dog in the manger, and one ought to rejoice in one’s friends’ happiness.” They were both a little hasty in their conclusions. The subject of these confidences between the cousins, which they pursued in the woods, at the river bank, in the drawing-room, and at tennis, was the inexhaustible discussion of the details of René’s adventures. On his return home, in the midst of the excitement, and the tearful joy of his mother, he had not been able to restrain himself from telling the whole story to her and to his cousin. For the subject had been tacitly ignored between him and the doctor, Caoudal having felt that his friend, if not hostile or sceptical, showed at least marked repugnance to encouraging him to speak of it.

As time went on, he became more and more animated and possessed by it, and, as the need of speaking and acting became more imperious, he showed that his heart was filled with thoughts of his mysterious acquaintances. Madame Caoudal appeared not incredulous, but displeased, cold, and even severe; she begged him seriously never to mention the subject in her presence again. Hélène never said a word, but her sparkling eyes spoke volumes; and when René, disappointed and perplexed, sought support and sympathy from her, she made him a sign to change the subject. “ Later, when they were seated under the great poplars which gave the name to their home, she explained her attitude:

“No need to torment auntie with the account of this wonderful adventure, or to let her brood over the projects that I understand,” said she. “You know what a grudge she bears to the sea; it is like a personal hatred between her and the liquid element. I believe she really thinks it a cursed power for evil. After the great sacrifice which she made in allowing you to enter the navy, we ought not to distress her any more than can be helped. If she believed, if it were possible for her to realize, that the depths of the sea, as well as its immensity, attract and claim you, that you feel called to the perilous honour of exploring unknown, mysterious, it may be deceptive regions, she, poor, dear soul, could not live. Spare her that distress.

“She has forbidden you to speak to her of such things. Obey her implicitly. As for me, I enter henceforth into all your plans; you know I have always shared your ambitions. Sometimes, nay often, I dream that I, too, pursue the glorious career of a sailor; I feel through my hair the vivifying air of the vast expanse; I fancy myself commanding a vessel; I see myself facing, with our brave seamen, the fury of the gale, landing on unknown islands, discovering new plants, new animals, new wonders, changing the aspect of geographical charts—and I wake—Hélène Rieux, as before!

“Do not think that I complain of my lot! But I admire and revere the glorious profession of my grandfather, of my uncle, and of yourself, and I shall be as proud of your exploits as if they were my own. All this is enough to show you that for these projects, still unformed, still indistinct, you should not seek any confidant except myself. You cannot be too careful. One only understands perfectly what one loves; and I feel strongly, myself, that nothing but a peculiar, hereditary influence could induce me to believe unhesitatingly and with absolute certainty in your veracity. Like other people, I see much that is incredible in your adventure, and yet I believe in it- That which convinces me is not, as with Stephen, my confidence in your good faith, the conviction of your clearheadedness, or even the proof of the ring. No, it is ‘the eye of faith’ voilà tout. It seems to me that it must be; because when one is a born explorer, one goes straight at the discovery; because you have been called to see that which others could not see. In short, I believe, because I believe!”

Nothing could be more satisfactory than a confidant of this sort, and René was not less anxious to tell than she to listen. Away with the false conclusions of Madame Caoudal, of Dr. Patrice and of other friends! Hélène and René, like accomplices, continually felt the need of some mysterious confabulation. Either René had omitted to give in detail some one perfection of his goddess, or else Hélène had some new hypothesis to suggest, or wished to be told over again some forgotten circumstance. And, above all, there was the increasing importance of the question:

How to find the enchanting abode of these august personages again? How to find the time, the means, of attempting it? How to do all without awakening any suspicion on the part of Madame Caoudal? Hélène was firmly resolved on two points: to spare René’s mother all uneasiness, all useless anxiety; and to encourage, as far as lay in her power, that which she considered to be the fulfilment of a duty, a chosen mission.

CHAPTER V

THE PLAN OF CAMPAIGN.

R

ENÉ was too clear-headed, and had been too long accustomed to weigh things in his mind with mathematical accuracy, not to have endeavoured to account for his immersion and subsequent adventure by simple and natural causes. He started with the following premises: First, I am not the sport of a hallucination, since I have in my possession a priceless and unique ring. Second, The old man and the young girl whom I saw in the wonderful grotto were not phantoms, because there are no such things as phantoms. Third, They are living beings, placed, by some combination of circumstances of which I am ignorant, in extraordinarily peculiar conditions of existence, at some hundreds of feet beneath the surface of the ocean, since the marine charts show in this region of the Atlantic a depth of not more than one thousand feet. And the habitation of these real and living, but abnormal beings? Clearly a grotto, or series of grottoes, extending under the sea, and borrowing the necessary respirable air from air-holes on the top of some rocks on a neighbouring island.

Such was the only reasonable conclusion he could arrive at. And it brought him by an easy transition to the question as to whether chance had not put him in the track of a great discovery, or at least of a great historical verification,—that of the ancient continent, now lost sight of under the ocean, which the tradition of the earliest times locates between Africa and South America; a sort of huge island, formerly analogous to Australia, long since submerged, and of which Madeira, Teneriffe, the Azores, and the Antilles are the only remains or landmarks now visible. As to the existence of this Atlantic continent, on the other side of the Pillars of Hercules (that is to say the Straits of Gibraltar), and of its disappearance during some great cataclysm, the historians, geographers, and philosophers of antiquity are all agreed. Plato speaks of it often in his writings. He gives us the source of the tradition which he hands down, and which is assuredly not without authority: it was his granduncle Solon, the Athenian legislator, who received from the Egyptian priests of Saïs a description of Atlantide, as they called this mysterious land.

To what branch of the human race did the Atlantes belong? On this point, tradition is less clear. Some have thought that they were an indigenous race which probably invaded Europe (that is to say Greece), and were opposed by the feeble resistance of the Pelasgi, the ancestors of the Greeks, Others believe, on the contrary, that Atlantide was a Greek colony, perhaps one of those founded by Jason and his companions on their search for the Golden Fleece. But all these writers are agreed in stating that Atlantide disappeared some thousands of years before the present era, and that the shallows, the banks of marine grass known by the name of “The Sea of Sargasses,” the peaks and the islands of this region, are, in some sort, the ruins of a submerged continent.

So much for the summary, but positive, indications gleaned by René from history. He knew, moreover, that the navigators of the fifteenth century believed in the existence of Atlantide. Christopher Columbus, for one, endeavoured to find his way to the Indies by going westward, with the conviction that he was sure to find, at various distances apart, the islands surviving from the great continent, which would serve him as places where he might put into port by the way. The discovery of the Azores and the Antilles justified, in a great measure, this idea, based, as it was, on traditional geography.

All the soundings made during the last half century, notably those by Admiral FIeuriot de Langle, in the part of the Atlantic between the twelfth and sixtieth degrees west longitude, show, moreover, a region literally “paved” with shallows, reefs, and sandbanks. In short, the actual conclusions drawn from the physiography of the globe forbade him to doubt any longer the possibility, and even the probability, of these facts relative to Atlantide and its disappearance. Considerable changes have been and still are produced, under our own eyes, in the configuration of sea and land, such as the sundering of the land at the Straits of Dover, which is of comparatively modern date. The coast of Normandy, too, was encroached upon by the sea, shortly before the Carlovingian era, and nothing was left above high-water mark but the Channel Islands, and, even in our own day, the Island of Santorin, in the middle of the Mediterranean, has disappeared from view.

Then new islands have appeared, while, in the far east, frightful inundations have changed, in a few days, the physiognomy of the Japanese Archipelago. It is well known, also, that America was in primitive times much less extensive than it is now; that the enormous basin of the Amazon, that of La Plata, Florida, Patagonia, Louisiana, and Texas, are lands but recently abandoned by the ocean. In a word, there are endless proofs in evidence of the fact that the surface of the globe is ceaselessly changing, sometimes by the slow and continued action of winds and waves, sometimes by the sudden effect of some great local disturbance.

René was able, therefore, without imprudence, to admit as certain the fact that an Atlantic country had been submerged beneath the ocean, and to connect this historical known quantity with the indelible remembrance of his submarine sojourn near the Azores. The more he looked into the subject, the more sure he felt that the old man and the young girl were Atlantes, veritable Atlantes in flesh and blood, surviving the wreck of their country. How? By what mysterious means? By what refined artifices? By what superhuman power? He could not tell, and he would not risk useless hypotheses in this regard. But he was certain of one thing; what he had seen once he was determined to see again; to bring to light this mystery; to elucidate, perhaps, a great geographical problem.

Why not, after all? Why not embark voluntarily, systematically, and with his eyes open, on this voyage which a sea wave had already unconsciously accomplished for him? Why not descend once more of his own accord to the scene he had left in an inanimate condition, and come and go at his own pleasure? René made up his mind to attempt it. And so, as he was accustomed to do thoroughly what he did at all, he asked himself, to begin with, by what means he could exchange ideas with these Atlantes, supposing he were fortunate enough to find them. At any price, he must avoid the blunder of knowing that they were discussing him, without being able to understand what they said. What language did they speak? The conviction was impressed more and more upon him that it was ancient Greek.

This conviction was corroborated by their surroundings, their furniture, by the character of their garb and their attitudes, and became a certainty one evening when he was talking to himself, aloud, about that which occupied his thoughts night and day. He had just mechanically articulated some of the sounds he remembered to have heard in the grotto:

“Pater, agathos, thugater” The next thing to do was to hunt up his old classic school-books, to open the Iliad and the Odyssey, and to search feverishly for these same words.

All at once scraps of Greek, long dormant in his memory, awoke from their sleep. The old roots of Claude Lancelot shone before him, in blazing characters, and he surprised himself muttering, as in former days: “Pater, father; apater, without a father; agathos, good, brave in war; thugater, the daughter is called —” Oh, charming roots! What delicious rhapsodies! How René enjoyed these phrases that he used to anathematize in his schoolboy days! He found out now what had from his mother to spend the time of that leave at sea. During this interval, he received his promotion to the rank of lieutenant. This was no more than his due, since, for the last year, his name had figured on the roll for promotion, for “distinguished services.” The first and immediate effect of this promotion was to facilitate the accomplishment of his projects, and he obtained, without difficulty, the necessary three months’ freedom.