The Crystal City Under the Sea (24 page)

“Dear aunt,” said Hélène, grieved at the state of mind to which her adopted mother was reduced, “ there is one consolation in our trouble, as Atlantis rightly says, and that is, that we are all together. Remember how you felt when we were so anxious about René’s fate! How different from this 1 If we must remain here a few years—”

“Mercy on us,” cried Madame Caoudal, “how you run on! Years! Do you think I have so .many years to lose? It is very singular, but since I have realized that we are prisoners, I feel I cannot breathe. Positively it is close here; don’t you find it so?”

“Mere fancy, I assure you, dear madame,” said Patrice. “There is plenty of air to breathe, and it is of extraordinary purity. The truth is that, with so much pressure under our sky, we could hardly expect to get it so purified. And the apparatus for producing oxygen, which I have just examined, is of marvellous perfection.”

“Hush, my dear Patrice,” interrupted Aunt Alice, driven into a corner; “don’t talk to me about oxygen apparatus, or of any cf the odious phantasmagoria we are living in, for you make me boil over with impatience. Oxygen! when I think of the pure air in my garden! Ah, my poor garden! And my house! It will be in a fine state! I feel morally certain that Jeannette will take advantage of my absence to let the dust accumulate in all the corners. Yesterday was the day for her to have a thorough cleaning of the large drawing-room! I’ll be bound she never touched it,—or perhaps has done it for form’s sake, without moving the furniture. These servants are all alike; the best of them are good for nothing!”

“Still, Jeannette is worth her weight in gold, I have often heard you say. Aunt Alice,” replied Hélène, glad to find that household cares had for the moment diverted her aunt’s mind from present troubles.

“Oh, no doubt! when I am there to superintend! But I ask you what she is likely to do, when I have left her for the purpose of gadding about a few hundred thousand feet below water! Fortunately no one knows where I am, for, upon my word, I should be ashamed for any of my acquaintances to hear of it! Just think what Madame Duthil or Madame Calvert would say!”

“It certainly would have a droll effect on them,” cried Hélène, with a fresh burst of laughter. “Madame Calvert has one deeply rooted idea: travellers see wonderful things. I have heard her say so scores of times. If we were to tell her about our adventures, she would have some reason to doubt the truth of them, I must own.”

“Still we will take care never to breathe a word about it, if we are ever fortunate enough to get out of this hole. Oh, dear! every minute seems a century! René, Stephen, what is your opinion? Shall we ever leave this place, or shall we not? Yes, or no? Tell me frankly. I had rather know what I have to expect!”

René had just reappeared upon the scene, followed by Kermadec. They had both been to look at the lower air-lock, which was empty and open.

“My dear mother,” said René, “I know you are courageous enough to prefer the truth to a reassuring lie. Yes, it is possible we may be able to get out; everything depends upon our being able to remove the boat that bars our passage. You have, none of you, any idea of the formidable weight of this steel-plated boat, lying against the Titania, We are five strong men (omitting of course Charicles); you are three women, who by rights should together be equal to the strength of one ordinary man. Well, with only this force at our disposal, it is practically impossible that we could succeed in moving the obstacle one inch.”

“Well, then, all is over with us, and we are buried alive,” said Madame Caoudal.

“Oh, no; for, though it is impossible for us, with our united strength, to raise the boat, we ought to succeed, with the help of the wonderfully powerful mechanical contrivances at our disposal, in this marvellous submarine workshop. It is well for us that we have fallen among people intellectually endowed like the Atlantes!”

“Very well!” said Madame Caoudal. “Let us set to work without delay; and how soon shall we be able to get out? for I declare every minute seems an age.”

“Alas! dear mother,” said .René, in a depressed tone, “ try to take courage. It grieves me sorely to think that it was to seek for me, that you came down to this tomb! “

“What do you mean?” said she, turning pale. “Will it be long?”

“A longtime.”

“A week? A fortnight?”

“Perhaps months, if not years, my poor mother. Think what a long time it must take, and how much there will be to do, before we can either set up the necessary machinery, or construct a new air-lock outside this one. We should have it all to do ourselves. Only keeping up our hopes can make our work successful.”

“Months, if not years!” repeated Madame Caoudal, utterly overwhelmed. “Ah, me! I shall never see France again. I beg your pardon for showing so little courage, but I declare the prospect freezes the blood in my veins! Years!”

“Oh, courage. Aunt Alice!” cried Hélène, taking her in her arms; “perhaps we may succeed sooner than that. And then, we are all together,—nothing can rob us of that satisfaction.”

“Nothing but death, which cannot be long coming in this tomb,” murmured Madame Caoudal. “Don’t you remember, Hélène,” added she with trembling lips, “the terror I have always had of being buried alive? Yes, since my early childhood it has been a perfect nightmare to me. I feel it now, I feel stifled, —look at me!”

”I entreat you, mother,” said René, well nigh desperate, “not to give way to these dismal thoughts. Cheer up! Don’t let us be cast down, but work our hardest. It will be the salvation of us.”

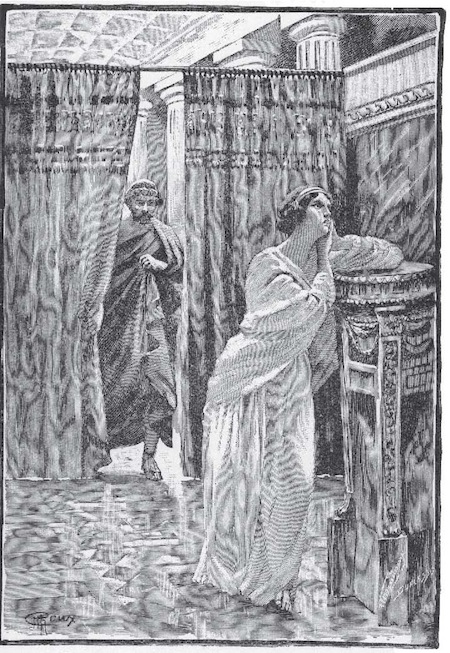

But it was in vain that René and Patrice tried to keep up her courage, she seemed more and more demoralized and completely prostrated; and the resolution shown by Hélène had no influence over her whatever. Monte Cristo, too, was in an equally lamentable condition. He sat, dejected, utterly spent, his arms hanging down, his eyes fixed on vacancy; very different from the smart cavalier of an hour ago. As for Sacripanti, squatting against the unlucky boat, he exhausted himself in futile efforts to raise it on its keel by shoving it with his shoulder. He seemed to have completely lost his head. All at once Atlantis, whose observant eyes had followed every change of expression on the faces of her companions, left them for a moment and flew to her father’s side. She soon reappeared at the door of the room, and, raising her clear voice, said: “René, Hélène! come, all of you, to my father. I have told him about your trouble, and he wishes to speak to you.”

Glad of this diversion, René took care that his mother should go with them to Charicles’s bedside. They had to support her, the account of the disaster had shocked her so much. They all stood at the foot of the bed, round the seat which Atlantis had placed for Madame Caoudal. The old man, raised up on his pillows, received his guests with a frank smile. The dignified calm of his brow, and the steady look in his deep-set eyes, made a great impression on them.

“You are looking better, father,” said René, involuntarily. “ It really looks as if you were going to regain your health yet.”

“Do not deceive thyself, my child,” replied he, with serenity. “ My hours are numbered; the lamp is going out for want of oil. This flash of light will be the last. But, before I die, I wish to confide to you an important secret. Atlantis, pour me out a few drops of our ancestors’ cordial. I have much to say, and my strength may not hold out.”

Atlantis quickly obeyed, and, having moistened his lips with the cup, he resumed:

“I have always thought to carry my secret to the grave, confiding it only to my daughter, who, in her turn, would confide it to her son, as has been the practice in the family through the ages. But in view of the distressing accident that has befallen these guests who will take my place by my orphan’s side, I hesitate no longer to impart it to them. René is quite right in thinking that it would take years to float the submarine boat again, if you should ever succeed in doing it. Happily there is another way of exit from the domain of Amphitrite. It is this. One of my ancestors, the sage Oulyssos, had lived all his days in Atlantide after it was submerged. He never had any desire to enjoy life outside its walls, convinced, from what he had read, that happiness did not exist on earth, and that the Atlantes were the only people who retained the secret of it.

“When he reached the age of twenty, his father married him to the lovely Eucharis. This young girl had been afflicted, from her childhood, with a strange melancholy. Subject to attacks of cataleptic sleep, she always awoke from them with apparent reluctance, very sad, and casting a homesick glance through the crystal vault of her prison. When she married Oulyssos, he succeeded, by pressing her with questions, in acquainting himself with the cause of her sadness. She was dying with the longing to visit the earth, to breathe the pure air, to bask in the life-giving rays of the sun. In the crises of her sleep, she imagined herself transported thither. She lived there like an ordinary mortal, running about in the woods, enjoying the sunshine, and gathering the fruit and flowers from mother earth. The moments when these visions were vivid were the only happy ones she had ever known since she heard of the existence of the outside world. Every day, she said, the walls which surrounded her weighed more heavily on her shoulders, like a cloak of lead. Unless Oulyssos wished to see her die before his eyes, he must find some means of piercing the blue-green shadows, and carry her towards the heavens, towards the stars, towards light and liberty.

“No one knew, at that time, of any means of rising to the surface. Deeply touched by the despair of his young wife, Oulyssos, who was a clever engineer, undertook to dig a tunnel extending to an island not far distant, in order to satisfy her desire of breathing the air of the living.

“Alas! before the twentieth part of it was constructed, poor, sad, homesick Eucharis had closed her eyes forever, without having once seen the blue sky, the subject of all her dreams. Oulyssos mourned her bitterly. But, even when, in obedience to his father’s wishes, he formed new ties with the charming Lalage, he never forgot his poor exiled Eucharis. Unwilling that another

The sorrow of Eucharis.

daughter of his race should perish like her, for want of seeing the earth, he continued to work at his tunnel, and, after years of labour, he finished it. That tunnel exists still. It is about thirty stadia

3

in length, and opens out on one of the Azores, a small island called Santa Maria, they tell me. By this road you can leave this place whenever you wish.”

Madame Caoudal’s joy on hearing this may be imagined, not to speak of that of the others, at the statement of this reassuring news. They each realized, when the heavy weight was lifted from their hearts, how very unpleasant it would be to stay for an indefinite time under the water. If they had listened to Sacripanti, they would have set out at once. But Madame Caoudal, notwithstanding her impatience, was unwilling to leave the dying man in the state he was in. She contented herself by asking, with a happy, relieved face, to be told where the entrance to the tunnel was.

“It is not very far off,” said Charicles, still calm and smiling; “it is behind the original wall of the grotto, under a mass of flowers. When you enter it, you have only to walk straight ahead, as soon as you have lighted the electric light. The floor is covered with fine sand, and the walls hung with choice creeping plants, for tapestry. You will walk, without fatigue, the thirty stadia on the road patiently excavated by my ancestor, and, at the end of it, you will find a crystal door fastened by a gold lock, and concealed by a rock at the bottom of a cave. This cave is on the shore of Santa Maria. Daughter, give me the sandalwood casket which is in my coffer; it holds the key.”

Atlantis hastened to open the large ivory coffer at the head of Charicles’s bed. She drew from it a sandalwood box of curious workmanship, and gave it to her father. The old man opened the casket, took out the key, and, after having shut his eyes for a, few moments and murmured a few words which sounded like an invocation, he handed it to his daughter, to whom, he said, it belonged by right, as the direct heiress of Oulyssos, Atlantis received it in respectful silence, fastened it to the gold chain she wore round her neck, and hid it in the loose folds of her snowy tunic. Charicles then drew from the casket a roll of papyrus, covered with ancient characters, and offered it to René.

“This,” said he, “is the complete history of the territory of Atlantide, from the -most remote times. Study it carefully, my son; thou wilt find in these pages fresh motives for venerating the race from which thy promised bride has sprung. And now,” added he, “ let us come to minor matters. Here is something which represents in a small space a fabulous sum; so my father told m^when he left it to me. It shall be the marriage portion of my daughter. I dare say these pearls, these products of the oyster, are of great value in your country. Am I right?”

So saying, Charicles untied a little leather bag scented with a strange and powerful perfume, and shook from it a handful of exquisite pearls. They were of all shapes and sizes, from that of a pea to that of an almond. They were so brilliant, of such milky whiteness, and so unmistakably of the first water, that there was a general exclamation of admiration. . Atlantis alone regarded them with indifference, while Madame Caoudal and Hélène declared they had never seen anything so splendid. Charicles, much pleased with the admiration they elicited, made Atlantis bring him a second casket from the ivory coffer, and handed it with dignified grace to his guests. It contained quite a collection of antique jewelry. Though far from being as valuable as the pearls, the jewels were very precious, both intrinsically and from the peculiarity of their setting. To Madame Caoudal he gave a chain of superb black pearls, so fine that a small thimble would almost have held them. The chain was made of the same unknown metal as the ring given by Atlantis to René at their first interview, and which had never since that day been taken from his finger. Besides this, Charicles begged Madame Caoudal’s acceptance of some long pins for pinning back her veil, made of gold, of most remarkable but exquisite workmanship; two clasps for a waist band, and several more clasps intended for fastening the peplum on the shoulder, as he explained to the good lady, who was inwardly horrified at the idea of appearing as a tragic muse. Then, turning to Hélène with a benevolent smile, the old man was pleased to clasp with his own hands two heavy gold bracelets round her slender wrists; to hang round her shapely neck a necklace of opals; and, lastly, to place in her beautiful hair some white bands embroidered with fine pearls, which gave her saucy face something of the beauty and grace of the ancients. Atlantis laughingly threw over her shoulders a long tunic of white linen like that which she herself wore, clapping her hands when she saw her transformed into a Greek, and looking so charming. It would indeed have been difficult to imagine a prettier picture than the two girls made. Patrice and René received each a ring, and Kermadec an enormous cup of mother-of-pearl, mounted in platinum and standing on a base of red coral. Charicles begged his guests to accept in addition a bale of rich tapestry.