The Crystal City Under the Sea (16 page)

And tears, like diamonds, shone in her gray-blue eyes, while their expression of filial piety only added to her loveliness in René’s eyes.

“Dear daughter,” murmured the old man, “do not grieve, child of my heart. If the gods will it, I shall regain my health, and, in any case, I thank them for having brought hither this young stranger, worthy, by his outward as well as his mental gifts, to be thy brother. See how afflicted he is; he feels thy grief, and would give me his strength if he could. All honour to him who knows how to respect old age! Perhaps he has a father, and thinks he recognizes one in me. Ask him, my daughter; learn from him under what heaven he first saw the light, by what chance he penetrated our dwelling. I will gladly listen, and without fatigue, and while opening my understanding to new ideas, I will await patiently the accomplishment of my destiny.”

Atlantis and René set to work to arrange the old man’s couch more comfortably, raising his head and moistening his lips and brow with a fragrant balm from a phial of exquisite shape. Atlantis placed herself near to him with one hand resting on his, and the other supporting her chin, her elbow on her knee, and, fixing her eyes on René:

“Speak, stranger,” said she; “explain to us whom thou art, whence thou comest, and of what race thou art, and tell us thy history. Charicles and his daughter are listening to thee. And do not forget that they who come from afar have need to guard their lips, so that they utter no words but those of truth. May the strictest sincerity govern you! We, poor recluses, isolated from the world, will listen to thee with respect, and may we draw from thy discourse the teaching and light we so much need!”

The liveliest approval of these sage words of his daughter was depicted in Charicles’s face, as René, with a bow and a smile, began his account of himself:

“You see in me,” began the young officer, somewhat abashed at being obliged to bring his personality so much to the front, “the son of a race doubtless unknown to you, for I presume, from all I see around me, that centuries have passed since the people of your nation have had the least intercourse with the outside world,—with ours, for instance?” The old man made a sign of assent. “But,” continued René, “have you never heard of a Greek colony, founded by your ancestors, called by the name of Phoenicia?”

“I know Phoenicia,” said Charicles; “dost thou come from that famous town, young man? Art thou our fellow countryman, a sort of distant cousin?”

“Fellow countryman? that would be going a long way back,” replied René, smiling; “but at least we have, no doubt, not altogether uncommon origin. It is certain that you, as we, belonged to the great family which learned men call Indo-European. The various nations springing from this source come from a people who originally inhabited the elevated plateau of central Asia. You do not need to be told by me that at a far distant period, long before the historic ages, this race emigrated and spread itself over a vast region of Asia and Europe. In Asia they were the parents of the Hindoos, who spoke Sanscrit; the Medes and Persians, who spoke Zend, were the other branch of the stock. In Europe, we find four principal races: the Germans, the Pelasgi, the Slavs, and the Celts. You are not ignorant of the fact that in ancient times the country which we call Greece, after the manner of the Romans, and which you doubtless know by the name of Hellas (from the name of the founder Hellen), was called at that time Pelasgia. Attica, and still more Arcadia, boasted of the nobility of their origin, and prided themselves on being branches of the only Pelasgic stock. It was the Pelasgi who spread themselves in the greatest numbers over Italy, the southern part of which country, from the number and importance of your colonies in it, being known for a long time by the name of Greater Greece, The Pelasgic language helped, consequently, to form the root of the Latin language, as did also that of the Greeks. I enlarge thus upon these details in order to show you that we have, indeed, a common origin, and that we are all branches of the same trunk, but with different degrees of culture.”

“I listen to thee with interest, stranger,” said Charicles; “wisdom pours from thy youthful lips. But, I beseech thee, tell me of the Phoenician city of which thou didst but now pronounce the name.”

“You know the origin of Phoenicia, founded by your illustrious compatriots, the Phoenicians of Ionia, two thousand one hundred years ago. Your merchants, speeding their frail barks along the Mediterranean, quickly recognized how much there was to be gained on our southern coasts. And yet, what dangers they ran! What snares were set for them! The Phoenician colony existed only by a miracle. On land, they were surrounded by powerful Gallic and Ligurian tribes, who fought for every inch of ground which they tried to gain. By sea, they encountered enormous Carthaginian or Etruscan fleets, which pitilessly massacred every stranger engaged in commerce with Sardinia. But your immortals protected them, doubtless, for everything favoured the Marsellais (the name by which at the present time the Phoenicians are known) without their having to draw the sword. The Syracusans destroyed Etruscan navigation, and Rome finished by absorbing all the commercial States. Carthage, Etruria, and Sicily succumbed. The Phoenicians would gladly have taken the place of Carthage, for which they seemed fitted by their economic and mercantile genius; but, not daring to aspire so high, they contented themselves with civilizing the barbarians (as they called my ancestors) in their immediate neighbourhood, and with founding numerous settlements along the Mediterranean coast from the Maritime Alps to Cape St. Martin, that is to say, as far as the first Carthaginian colonies.

“If you ask me now what the people were like who inhabited the region to the north of the Phoenician colony, the people from whom I am descended, I will describe them to you by the mouth of an

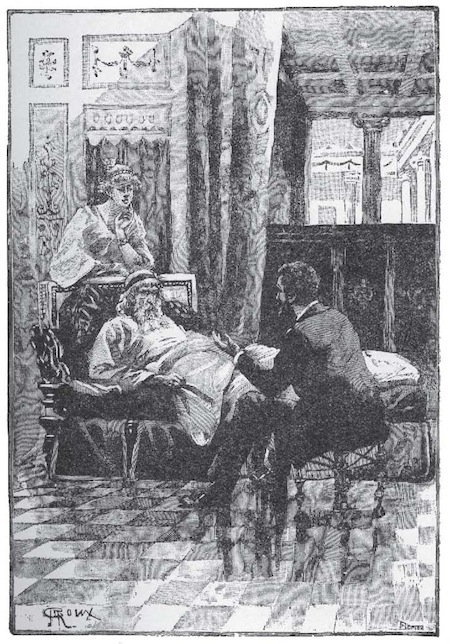

René telling his story.

ancient historian.

2

The character of the Gallic race, according to the philosopher, Posidonius, is irritable and warlike, always ready to strike, but withal simple and without malignity; if they are irritated, they attack a foe straight in the face, without thinking of anything else. But one can always succeed with them by strategy; one can at any time provoke them to combat, however unimportant the motives leading up to it may be; they are always ready, even without any weapons, save those of strength and audacity. Nothwithstanding, they are easily induced to learn useful things; they are susceptible of culture and literary instruction. Strong in their powerful physique and in their numbers, they quickly assemble in bands; and, simple and spontaneous as they are, willingly take in hand the cause of the oppressed. That is one of the first judgments passed upon my race by philosophy.”

“A fine trait, the last,” said Charicles, nodding his venerable head, “taking in hand the cause of the oppressed. That is a characteristic worthy of admiration.”

“And one that has been true all through my country’s glorious history,” said René, with a proud light in his eyes. “Yes, I can truly say that no nation has played the part of leader as mine has done. Always in the van of light and liberty, France has been the enlightener of the world, and there is not a generous idea, but has found an echo among her people. She has replaced Greece in the mission of civilization.”

“Replaced!” quickly interrupted Charicles. “Has Hellas then disappeared?”

“ From a political point of view, yes. That cannot be denied. Her greatness, which radiated over ancient civilization, and whose influence governs us to this day, became extinct under the domination of Rome, about a hundred and forty-five years before our era. But what incomparable brilliancy was shown by the people of that small territory! Science, the arts, war,—the Greeks excelled in all. To this day, we are lost in admiration at the contemplation of what was wrought by their hand, their pen, and their powerful and cultivated intellect You cannot have heard, Charicles, of the marvellous sons your country has produced. Perhaps you do not even know the name of Phidias, or of Euripides, of Socrates, Aristotle, or Plato? Well, we modems of the civilized world base our principal studies upon their works. He who ignores them is considered to be wanting in culture, a sort of Helot. You find nowhere else more beautiful creations of art than those of Greece. They are copied, admired, venerated. They are equalled sometimes, but never surpassed, for they have attained to perfection of every kind.”

“Thy words are very precious, young man, and cheer me like generous wine,” exclaimed Charicles, with energy. “ And see how moved Atlantis is also; she drinks in thy discourse, and feels proud of her race.”

“Yes,” said Atlantis, “it is sweet to me to hear the praises of my nation, stranger, although it is cruel to learn that she has fallen. We know nothing of her ancient glory, but the poems of the great Homer. Tell me, do people still read them? Hast thou ever read them, traced on silky papyrus; dost thou know the king of men, Agamemnon; and Helen, more beautiful than Aphrodite, and the traitor, Paris?”

“And Ajax, and Hector, and Ulysses, and old Nestor! Have I not dug out their roots on the school forms!” cried René, laughing. “Yes, I know them, less than I ought to, no doubt, but it is in studying the divine Homer that the youth of my nation spend the greater part of their school days. We have learned men who examine into his writings all their life long, and there must be a whole library of books written on his poem.”

“Doubtless, you have none of them, you barbarians,” said Atlantis, simply.

“We have some, certainly,” said René, somewhat piqued, “and if you will accept me as French master, I will make them known to you, fair Atlantis. But I confess we have no poet to equal Sophocles or Euripides, neither has sculptor of ours ever surpassed the divine Phidias; and yet, ours are the best in the world.”

“And how is it that you have reached this preeminence?” continued Atlantis with interest. “Are you our direct inheritors? Is it through the Phoenicians that you have learnt our secrets?”

“It would take rather long to explain to you,” said René. “However, I will try.” And, adapting himself to the comprehension of his auditor, the young officer called to his aid all his acquaintance with ethnological, scientific, artistic, and historical lore, and, after having described to them the Gallic, Frank, and Breton characteristics, he took up the chief threads of the world’s history, from the time when they seemed to have lost them, which appeared to date from about the time of the foundation of Phoenicia, that is to say, about six hundred years before our era.

It was a lengthy task; but, curious and attentive, the two solitary beings were unwilling to lose a single thread in the weaving of events; and if their improvised teacher had spoken all night long, he would have been listened to with the same interest. Fatigued, at last, with his long lecture, René, who had conducted them as far as the state of Europe in 189—, paused out of breath, and a long, thoughtful silence reigned among them.

Charicles was the first to break it. “All that thou hast taught me has astonished me much, young stranger,” said he at length. “What marvels, what events, what vicissitudes! O my country, thou that wert of small extent in the world, and yet so great by the majesty of thy genius, blessed be thou! I must die without ever having pressed my lips to thy sacred soil; but before descending to Hades, I bless the gods for having brought this stranger, who has revealed to me thy greatness and thy glory. I should like, stranger, to give thee the history of my race, to make thee understand how it comes about that we are here, but I am overcome with fatigue. My limbs are heavy, and my tongue inert and useless. Let Atlantis take my place and instruct thee; her harmonious voice will charm thee, while she will lull to rest my last hours in this world. Speak, dear child, and we will listen, reverencing in thee the triple majesty of beauty, innocence and knowledge! Forget nothing that can instruct this young man, and, while giving him the story after thine own manner, let the polished mirror of strict truth preside over the threshold of thy lips. Speak, and may Pallas dictate thy words.”

Atlantis bowed her head modestly to her father; then, without waiting to be asked a second time, “I obey thee, noble Charicles,” said she. “And thou, stranger, be indulgent, if my lips, still young and inexperienced, err sometimes in my story. Charicles has taught me all I know. If my words please and interest thee, to him be all the honour.”

CHAPTER XV

THE STORY OF ATLANTIS.

W

HAT I am about to relate to thee, stranger, and to thee, father, is a very ancient tradition. It reaches back among the years as far as two or three thousand lustra. I give it to thee as I have received it from Charicles’s venerable lips, who himself learnt it from those of his noble father, Antigoras, In his turn he received it from his father, and so on, back through the night of ages. Often, since the time when my childish head hardly reached his knee, he guided my finger, while I spelt on the papyrus the ancient traditions of our ancestors.

“At first, our fathers lived on earth, even as yours; and the bottom of the sea, unknown to human eyes, was inhabited only by the monsters of the deep, Tritons and sea-nymphs. Our country was then a vast continent extending beyond the Pillars of Hercules, in the direction of newly discovered territory, named as thou hast told us, America. It was one of those colonies of which thou hast spoken, young man. But how flourishing! To what a degree of power you must have attained, oh, my ancestors, in the arts of peace and war! Thou speakest of Phidias, of Scopas, of Praxiteles. I do not know what they did. But, before seeing the chefs-d’oeuvre shaped by their chisels, I should hardly bring myself to confess that they could do better than our masters, whose memories we piously retain, whose masterpieces have been copied by our decorative painters.