The Crow (67 page)

Authors: Alison Croggon

As John Carroll points out in his study

The Elidhu of Edil-Amarandh: Traces of the Absolute,

17

Hem's initial meeting with Nyanar, in stark contrast with Maerad's dialogues with Arkan, culminates in wordlessness, a profound experience of Elemental "music." It is deeply ambiguous: at once an experience of inexpressible beauty, it also opens Hem to obliterating terror. Perhaps the most unsettling evocation of this terror – a fear of the inhuman implacability of the natural world – is Hem's Elidhu-inspired dream, "He watches as the impossible wave surges inexorably toward him, swallowing the earth in its path. It will devour everything, even the clouds. Mercy is a human vice; the wave knows nothing of it. Soon everything will be silent."

18

As the author of the

Naraudh Lar-Chane

comments, "The music of the Elidhu was shot with darkness, which both deepened its mystery and beauty and drew it far beyond Hem's grasp. The Elidhu were neither good nor evil; such words were invented by human beings to explain human actions."

19

Against this vision of amoral destruction is posited something more benign, an idea of "at homeness." Nyanar speaks of the landscape as "home," but his environment is, literally, his being. "This is myself," he tells Hem at one point, speaking of the landscape; and at another, "I am all that is here. There is no here that is not me." This is also evident when the Winterking speaks of the anguish of his banishment from Arkan-da. Place is more than a location to inhabit: it is the ground of an Elidhu's being.

In many ways the Elidhu are anarchic, and deeply antagonistic to Bardic ideas of the social Balance. As Dr. David Lloyd argues in his provoking meditation on the place of the Elidhu in the

Naraudh LarChane,

one of the defining aspects of the Elementals is their direct challenge to Bardic ideas of rationalistic causality. This is expressed in part through a different experience of time, which Lloyd characterizes as

mythic

time. "Time is not as you know it, you mortal creatures," Nyanar tells Hem. "To us it is a sea, and all times exist together. Nothing is truly gone..." The Elidhu concept of time, as a primordial place of origin, is an idea familiar to us through ritual, which is always a return to origin and creation. In cultures as diverse as the Australian Arunta, the New Guinean Kai, or in Hindu or Tibetan or Catholic ritual, appeal is made to a "beginning" as an expression of the "true" and the "sacred," which authorizes human meaning.

20

The Elidhu's actual experience of primordial or mythic time, and their concomitant understanding that all times coexist, challenges the rational historicism of the Bards in fundamental ways, and at least partly explains the Bardic distrust of the Elidhu as fickle and dangerous, as "pathological." The Elidhu represented a possibility of renewal and even, perhaps, of revolution, which, after the Restoration, the Annaren Bards sought to repress. David Lloyd in

Elements of the Sublime

writes:

Myth... is not defined by its content, but by its temporal structure. That is, where Adorno and Horkheimer emphasize the anthropomorphic tendency that defines myth for them as against the abstraction of reason, I would stress – against that still historicist division of the mythic (as past and as a relation to the past) from the enlightened – precisely what historicism itself distrusts as myth – its appearance as the rhythmic return of the past in an uneasy haunting of progress by the ghosts of its unfinished business.

21

It is the persistence and insistence of the archaic that reason should have eradicated, exhibiting the tenacity of irrational attachments and the violence of primordial drives. The putatively archetypal content of the Elidhu is less significant, however readily invoked, than its unruly capacity to return. In this, of course, the Elidhu share the characteristics of the unconscious to which, on a social and an individual level, they are generally assimilated... Insofar as Bardic historicism itself participates in the rationalization that represses the past and reduces its multiple forms to a single, serial narrative, it must perforce envisage the mythic Elemental as pathological. Where myth was, historical time must come, to lay the past to rest and cure its violence with reason and progress. The therapeutic drive of historicism, which relates the universal narrative of civility, is thus peculiarly repressive, seeking less to release the past in the unruliness of its everpresent possibilities than to discipline it.

22

Banished from Annaren history after the Restoration, the Elidhu nevertheless haunt Edil-Amarandh as unfinished business; behind their unacknowledged or demonized presence is the forgotten crime of the transcription and theft of the Treesong, in which both the Light and Dark were equally culpable. As Cadvan says at the end of

The Riddle,

"This is a matter of undoing what Light or Dark should never have done."

On the other hand, as is shown by Nyanar's persistence even in the midst of Sharma's wreckage of his "home," the Elidhu are also harbingers of possibility. Lloyd argues elsewhere that the Elementals demonstrate the reconnection of the past with the present, not as a process of nostalgia, but as reclamation of a possible future. "The work of history is not merely to contemplate destruction, but to track through the ruins of progress the defiles that connect the openings of the past to those of the present," he says. Through the figure of Nyanar, present despite the degraded and poisoned environment that Sharma has made of his place and self, "the form of the imagined future is sketched in the ruins of the present."

23

One might add that, as symbols of a natural environment betrayed and exploited by a civilization now long vanished, the Elidhu resonate uneasily into our own present.

T

HE

T

REESONG

R

UNES

At the end of

The Riddle,

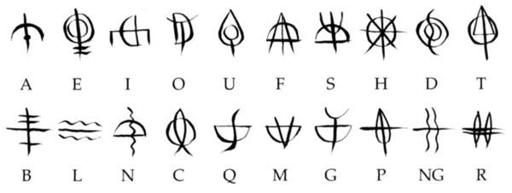

I include some notes on the Treesong runes, to which I refer interested readers. The Treesong was an alphabet of twenty symbols. Ten – those with the phonetic values A, E, I, O, U, F, S, H, D, and T – were inscribed on Maerad's Dhyllic lyre. The other runes – B, L, N, C, Q, M, G, P, NG, and R – were on the tuning fork stolen by Ire from the Iron Tower.

Each Treesong rune was a complex constellation of meaning, even if considered only in its lexical sense. It was not only a letter with a phonetic value; it encoded a line of the twenty-line poem that made up the Treesong, and also worked as a calendar, with the fifteen consonants symbolizing different seasons or significant days, and the vowels representing phases of the moon. Each rune was also associated with a

different tree, each of which had its own network of associations. The

density of symbolism associated with each rune is made even more complex by the suggestion of both Nyanar and Arkan that the runes as writing were significantly incomplete: that to be wholly meaningful, they required music. The source of their power is, like the Speech, only imperfectly understood.

The complete Treesong stanzas (with the moon-associated runes running first, and the others in seasonal order) now reads:

I am the dew on every hill

I am the leap in every womb

I am the fruit of every bough

I am the edge of every cliff

I am the hinge of every question

I am the song of seven branches

I am the gathering sea foam and the waters beneath it

I am the wind and what is borne by the wind

I am the falling tears of the sun

I am the eagle rising to a cliff

I am all directions over the face of the waters

I am the flowering oak that transforms the earth

I am the bright arrow of vengeance

I am the speech of salmon in the icy pool

I am the blood that swells the leafless branch

I am the hunter's voice that roars through the valley

I am the valor of the desperate roe

I am the honey stored in the rotting hive

I am the sad waves breaking endlessly

The seed of woe sleeps in my darkness and the seed of gladness

In an unpublished monograph, Professor Patrick Insole of the Department of Ancient Languages at the University of Leeds has made a thorough study of the extant sources on the Treesong, and on the symbolism of the runes.

24

1 have drawn extensively on his monograph for this book, and Professor Insole, generally regarded as the foremost authority on the scripts of Edil-Amarandh, has kindly permitted me to quote extensively from his monograph for these notes.

The runes on the tuning fork and the stanzas and values pertaining to them

B I am the song of seven branches

L I am the gathering sea foam and the waters beneath it

N I am the wind and what is borne by the wind

C I am the speech of salmon in the icy pool

Q I am the blood that swells the leafless branch

M I am the hunter's voice that roars through the valley

G I am the valor of the desperate roe

P I am the honey stored in the rotting hive

NG I am the sad waves breaking endlessly

R The seed of woe sleeps in my darkness and the seed of gladness

B L N C Q M G H NG R | Birt Lran Nerim Coll Ku Muin Gordh Phia Ngierab Raunar | Winter Winter Spring Summer Autumn Autumn Autumn Winter Winter Midwinter Day |

Some conjectural interpretations of the rune designs

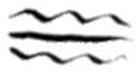

WINTER

is indicated as a flat line, which has been interpreted as representing ice or, more opaquely, as simply the absence of sun/light.

B is represented by seven branches, referring to the stanza "I am the song of the seven branches." It also appears to represent a tree in winter.

B is represented by seven branches, referring to the stanza "I am the song of the seven branches." It also appears to represent a tree in winter.

L shows two levels of water, one above and one below the central horizon, referring to the line "I am the gathering sea foam and the waters beneath it."

L shows two levels of water, one above and one below the central horizon, referring to the line "I am the gathering sea foam and the waters beneath it."

SPRING

is indicated by a rising sun motif, perhaps representing growth or the coming of light.