The Crimean War (28 page)

Authors: Orlando Figes

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Europe, #Other, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Crimean War; 1853-1856

During a second bombardment, on 12 May, one of the British ships, a steamer called the

Tiger

, ran hard aground in dense fog and was heavily shelled from the shore. Her crew was captured by a small platoon of Cossacks commanded by a young ensign called Shchegolov. The British attempted to burn their ship, while Odessa ladies with their parasols watched the action from the embankment, where bits of shipwreck, including boxes of English rum, were later washed ashore. The Cossacks marched off the British crew (24 officers and 201 men) and imprisoned them in the town, where they were subjected to humiliating taunts from Russian sailors and civilians, whose sense of outrage at the timing of the attack over the Easter period had been encouraged by their priests, though the captain of the ship, Henry Wells Giffard, who had been injured by shellfire and died of gangrene on 1 June, was given a full military burial in Odessa and, in an act of chivalry from a bygone age, a lock of his hair was sent to his widow in England. The cannon of the

Tiger

were displayed in Odessa as war trophies.

q

Tiger

, ran hard aground in dense fog and was heavily shelled from the shore. Her crew was captured by a small platoon of Cossacks commanded by a young ensign called Shchegolov. The British attempted to burn their ship, while Odessa ladies with their parasols watched the action from the embankment, where bits of shipwreck, including boxes of English rum, were later washed ashore. The Cossacks marched off the British crew (24 officers and 201 men) and imprisoned them in the town, where they were subjected to humiliating taunts from Russian sailors and civilians, whose sense of outrage at the timing of the attack over the Easter period had been encouraged by their priests, though the captain of the ship, Henry Wells Giffard, who had been injured by shellfire and died of gangrene on 1 June, was given a full military burial in Odessa and, in an act of chivalry from a bygone age, a lock of his hair was sent to his widow in England. The cannon of the

Tiger

were displayed in Odessa as war trophies.

q

Priests declared the capture of the British steamer a symbol of divine revenge for the attack on Holy Saturday, which they pronounced had begun a religious war. The washed-up liquor was soon consumed by the Russian sailors and workers at the docks. There were drunken brawls, and several men were killed. Parts of the ship were later sold as souvenirs. The Cossack ensign Shchegolov became a popular hero overnight. He was commemorated almost as a saint. Bracelets and medallions were made with his image and sold as far away as Moscow and St Petersburg. There was even a new brand of cigarettes manufactured in Shchegolov’s name with his picture on the box.

10

10

The bombardment of Odessa announced the arrival of the Western powers near the Danubian front. Now the question was how soon the British and the French would come to the aid of the Turks against the Russians at Silistria. Fearful that a continuation of the offensive towards Constantinople would end badly for Russia, Paskevich wanted to retreat. On 23 April he wrote to Menshikov, the newly appointed commander-in-chief of Russian forces in the Crimea:

Unfortunately we now find marshalled against us not only the maritime powers but also Austria, supported, so it appears, by Prussia. England will spare no money to bring Austria in on her side, for without the Germans they can do nothing against us … . If we are going to find all Europe ranged against us then we will not fight on the Danube.

Throughout the spring, Paskevich dragged his heels over the Tsar’s orders to lay siege to Silistria. By mid-April, 50,000 troops had occupied the Danubian islands opposite the town, but Paskevich delayed the commencement of the siege. Nicholas was furious with the lack of vigour his commander showed. Although he himself admitted that Austria might join Russia’s foes, Nicholas sent an angry note to Paskevich, urging him to begin the assault. ‘If the Austrians treacherously atttack us,’ he wrote on 29 April, ‘you have to engage them with 4 Corps and the dragoons; that will be quite enough for them! Not one word more, I have nothing more to add!’

It was only on 16 May, after three weeks of skirmishing had given them control of the high ground to the south-west of Silistria, that the Russians at last began their bombardment of the town, and even then Paskevich focused his attack on its outer defences, a semicircle of stone forts and earthworks several kilometres from the fortress of Silistria itself. Paskevich hoped to wear down the opposition of the Turks and allow his troops to assault the town without major losses. But the officers in charge of the siege operations knew this was to hope in vain. The Turks had used the months since the Porte’s declaration of war against Russia to build up their defences. The Turkish forts had been greatly strengthened by the Prussian Colonel Grach, an expert on entrenchments and mining, and they were relatively little damaged by the Russian guns, although the key redoubt, the earthworks known as the Arab Tabia, was so battered by the Russian shells and mines that it had to be rebuilt by the Turks several times during the siege. There were 18,000 troops in the Turkish forts, most of them Egyptians and Albanians, and they fought with a spirit of defiance that took the Russians by surprise. In the Arab Tabia the Ottoman forces were led by two experienced British artillery officers, Captain James Butler of the Ceylon Rifles and Lieutenant Charles Nasmyth of the Bombay Artillery. ‘It was impossible not to admire the cool indifference of the Turks to danger,’ Butler thought.

Three men were shot in the space of five minutes while throwing up earth for the new parapet, at which only two men could work at a time so as to be at all protected; and they were succeeded by the nearest bystander, who took the spade from the dying man’s hands and set to work as calmly as if he were going to cut a ditch by the road-side.

Realizing that the Russians needed to get closer to cause any damage to the forts, Paskevich ordered General Shil’der to begin elaborate engineering work, digging trenches to allow artillery to be brought up to the walls. The siege soon settled into a monotonous routine of dawn-to-dusk bombardment by the Russian batteries, supported by the guns of a river fleet. There had never been a time in the history of warfare when soldiers were subjected to so much constant danger for so long. But there was no sign of a breakthrough.

11

11

Butler kept a diary of the siege. He thought the power of the heavy Russian guns had ‘been much exaggerated’ and that the lighter Turkish artillery were more than a match for them, although everything was conducted by the Turks ‘in a slovenly manner’. Religion played an important role on the Turkish side, according to Butler. Every day, at morning prayers by the Stamboul Gate, the garrison commander Musa Pasha would call upon his soldiers to defend Silistria ‘as becomes the descendants of the Prophet’, to which ‘the men would reply with cries of “Praise Allah!”’

r

There were no safe buildings in the town but the inhabitants had built caves where they took shelter during the day’s bombardment. The town ‘appeared deserted with only dogs and soldiers to be seen’. At sunset Butler watched the closing round of Russian shots come in from the fortress walls: ‘I saw several little urchins, about 9 or 10 years old, actually chasing the round shot as they ricocheted, as coolly as if they had been cricket balls; they were racing to see who would get them first, a reward of 20 peras being given by the Pasha for every cannon ball brought in.’ After dark, he could hear the Russians singing in their trenches, and ‘when they made a night of it, they even had a band playing polkas and waltzes’.

r

There were no safe buildings in the town but the inhabitants had built caves where they took shelter during the day’s bombardment. The town ‘appeared deserted with only dogs and soldiers to be seen’. At sunset Butler watched the closing round of Russian shots come in from the fortress walls: ‘I saw several little urchins, about 9 or 10 years old, actually chasing the round shot as they ricocheted, as coolly as if they had been cricket balls; they were racing to see who would get them first, a reward of 20 peras being given by the Pasha for every cannon ball brought in.’ After dark, he could hear the Russians singing in their trenches, and ‘when they made a night of it, they even had a band playing polkas and waltzes’.

Under growing pressure from the Tsar to seize Silistria, Paskevich ordered more than twenty infantry assaults between 20 May and 5 June, but still the breakthrough did not come. ‘The Turks fight like devils,’ reported one artillery captain on 30 May. Small groups of men would scale the ramparts of the forts, only to be repulsed by the defenders in hand-to-hand fighting. On 9 June there was a major battle outside the main fortress walls, after a large-scale Russian assault had been beaten back and the Turkish forces followed up with a sortie against the Russian positions. By the end of the fighting there were 2,000 Russians lying dead on the battlefield. The next day, Butler noted,

numbers of the townspeople went out and cut off the heads of the slain and brought them in as trophies for which they hoped to get a reward, but the savages were not allowed to bring them within the gates. A heap of them however were left for a long time unburied just outside the gate. While we were sitting with Musa Pasha, a ruffian came out and threw at his feet a pair of ears, which he had cut from a Russian soldier; another boasted to us that a Russian officer had begged him for mercy in the name of the Prophet, but that he had drawn his knife and in cold blood had cut his throat.

The unburied Russians lay on the ground for several days, until the townspeople had stripped them of everything. Albanian irregulars also took part in the mutilation and looting of the dead. Butler saw them a few days later. It was ‘a disgusting sight’, he wrote. ‘The smell was already becoming very offensive. Those who were in the ditch had all been stripped and were lying in various attitudes, some headless trunks, others with throats half out, arms extended in the air or pointing upwards as they fell.’

12

12

Tolstoy arrived at Silistria on the day of this battle. He had been transferred there as an ordnance officer with the staff of General Serzhputovsky, which set up its headquarters in the gardens of Musa Pasha’s hilltop residence. Tolstoy enjoyed the spectacle of battle from this safe vantage point. He described it in a letter to his aunt:

Not to mention the Danube, its islands and its banks, some occupied by us, others by the Turks, you could see the town, the fortress and the little forts of Silistria as though on the palm of your hand. You could hear the cannon-fire and rifle shots which continued day and night, and with a field-glass you could make out the Turkish soldiers. It’s true it’s a funny sort of pleasure to see people killing each other, and yet every morning and evening I would get up on to my cart and spend hours at a time watching, and I wasn’t the only one. The spectacle was truly beautiful, especially at night … At night our soldiers usually set about trench work and the Turks threw themselves upon them to stop them; then you should have seen and heard the rifle-fire. The first night … . I amused myself, watch in hand, counting the cannon shots that I heard, and I counted 100 explosions in the space of a minute. And yet, from near by, all this wasn’t at all as frightening as might be supposed. At night, when you could see nothing, it was a question of who would burn the most powder, and at the very most 30 men were killed on both sides by these thousands of cannon shots.

13

Paskevich claimed that he had been hit by a shell fragment during the fighting on 10 June (in fact he was unwounded) and gave up the command to General Gorchakov. Relieved no longer to be burdened with responsibility for an offensive he had come to oppose, he rode off in his carriage back across the Danube to Ia

i.

i.

i.

i.On 14 June the Tsar received news that Austria was mobilizing its army and might join the war against Russia by July. He also had to contend with the possibility that at any moment the British and the French might arrive to relieve Silistria. He knew that time was running out but ordered one last assault on the fortress town, which Gorchakov prepared for the early hours of 22 June.

14

14

By this time the British and the French were assembling their armies in the Varna area. They had begun to land their forces at Gallipoli at the beginning of April, their intention being to protect Constantinople from possible attack by the Russians. But it soon became apparent that the area was unable to support such a large army, so after a few weeks of foraging for scarce supplies, the allied troops moved on to set up other camps in the vicinity of the Turkish capital, before relocating well to the north at the port of Varna, where they could be supplied by the French and British fleets.

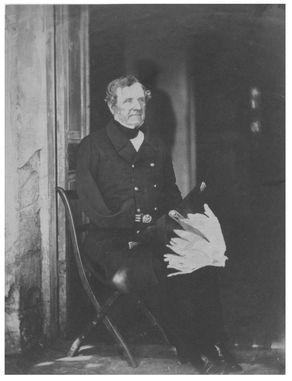

The two armies set up adjacent camps on the plains above the old fortified port – and eyed each other warily. They were uneasy allies. There was so much in their recent history to make them suspicious. Famously, Lord Raglan, the near-geriatric commander-in-chief of the British army, who had served as the Duke of Wellington’s military secretary during the Peninsular War of 1808–14 and had lost an arm at Waterloo,

s

would on occasion refer to the French rather than the Russians as the enemy.

s

would on occasion refer to the French rather than the Russians as the enemy.

Lord Raglan

Other books

When You Were Mine (Adams Sisters) by Byrd, Adrianne

The Hum by D.W. Brown

Playing With Matches by Carolyn Wall

Borrowed Cowboy (Shadow Maverick Ranch) by Parker Kincade

Amanda Scott by The Bath Quadrille

Night at the Fiestas: Stories by Kirstin Valdez Quade

Her Marine Bodyguard by Heather Long

Schreiber's Secret by Radford, Roger

Desire Me More by Tiffany Clare

Deadly Weakness (Gray Spear Society) by Siegel, Alex