The Crimean War (18 page)

Authors: Orlando Figes

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Europe, #Other, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Crimean War; 1853-1856

The success of the Russian intervention in the Danubian principalities influenced the Tsar’s decision to intervene in Hungary in June 1849. The Hungarian revolution had begun in March 1848, when, inspired by the events in France and Germany, the Hungarian Diet, led by the brilliant orator Lajos Kossuth, proclaimed Hungary’s autonomy from the Habsburg Empire and passed a series of reforms, abolishing serfdom and establishing Hungarian control of the national budget and Hungarian regiments in the imperial army. Faced with a popular revolution in Vienna, the Austrian government at first accepted Hungarian autonomy, but once the revolution in the capital had been suppressed the imperial authorities ordered the dissolution of the Hungarian Diet and declared war on Hungary. Supported by the Slovak, German and Ruthenian minorities of Hungary, and by a large number of Polish and Italian volunteers who were equally opposed to Habsburg rule, the Hungarians were more than a match for the Austrian forces, and in April 1849, after a series of military stalemates, they in turn declared a war of independence against Austria. The newly installed 18-year-old Emperor Franz Joseph appealed to the Tsar to intervene.

Nicholas agreed to act against the revolution without conditions. It was basically a question of solidarity with the Holy Alliance – the collapse of the Austrian Empire would have dramatic implications for the European balance of power – but there was also a connected issue of Russia’s self-interest. The Tsar could not afford to stand aside and watch the spread of revolutionary movements in central Europe that might lead to a new uprising in Poland. The Hungarian army had many Polish exiles in its ranks. Some of its best generals were Poles, including General Jozef Bem, one of the main military leaders of the 1830 Polish uprising and in 1848–9 the commander of the victorious Hungarian forces in Transylvania. Unless the Hungarian revolution was defeated, there was every danger of its spreading to Galicia (a largely Polish territory controlled by Austria), which would reopen the Polish Question in the Russian Empire.

On 17 June 1849, 190,000 Russian troops crossed the Hungarian frontier into Slovakia and Transylvania. They were under the command of General Paskevich, the leader of the punitive campaign against the Poles in 1831. The Russians carried out a series of ferocious repressions against the population, but themselves succumbed in enormous numbers to disease, especially cholera, in a campaign lasting just eight weeks. Vastly outnumbered by the Russians, most of the Hungarian army surrendered at Vilagos on 13 August. But about 5,000 soldiers (including 800 Poles) fled to the Ottoman Empire – mostly to Wallachia, where some Turkish forces were fighting against the Russian occupation in defiance of the Balta Liman convention.

The Tsar favoured clemency for the Hungarian leaders. He was opposed to the brutal reprisals carried out by the Austrians. But he was determined to pursue the Polish refugees, in particular the Polish generals in the Hungarian army who might become the leaders of another insurrection for the liberation of Poland from Russia. On 28 August the Russians demanded from the Turkish government the extradition of those Poles who were subjects of the Tsar. The Austrians demanded the extradition of the Hungarians, including Kossuth, who had been welcomed by the Turks. International law provided for the extradition of criminals, but the Turks did not regard these exiles in those terms. They were pleased to have these anti-Russian soldiers on their soil and granted them political asylum, as liberal Western states had done on certain conditions for the Polish refugees in 1831. Encouraged by the British and the French, the Turks refused to bow to the threats of the Russians and the Austrians, who broke off relations with the Porte. Responding to Turkish calls for military aid, in October the British sent their Malta squadron to Besika Bay, just outside the Dardanelles, where they were later joined by a French fleet. The Western powers were on the verge of war against Russia.

By this stage the British public was up in arms about the Hungarian refugees. Their heroic struggle against the mighty tsarist tyranny had captured the British imagination and once again fired up its passions against Russia. In the press, the Hungarian revolution was idealized as a mirror image of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when the British Parliament had overthrown King James II and established a constitutional monarchy. Kossuth was seen as a very ‘British type’ of revolutionary – a liberal gentleman and supporter of enlightened aristocracy, a fighter for the principles of parliamentary rule and constitutional government (two years later he was welcomed as a hero by enormous crowds in Britain when he went there for a speaking tour). The Hungarian and Polish refugees were seen as romantic freedom-fighters. Karl Marx, who had come to London as a political exile in 1849, began a campaign against Russia as the enemy of liberty. Reports of repression and atrocities by Russian troops in Hungary and the Danubian principalities were received with disgust, and the British public was delighted when Palmerston announced that he was sending warships to the Dardanelles to help the Turks stand up against the Tsar. This was the sort of robust foreign policy – a readiness to intervene in any place around the world in defence of British liberal values – that the middle class expected from its government, as the Don Pacifico affair would show.

g

g

The mobilization of the British and French fleets persuaded Nicholas to reach a compromise with the Ottoman authorities on the refugee issue. The Turks undertook to keep the Polish refugees a long way from the Russian border – a concession broadly in line with the principles of political asylum recognized by Western states – and the Tsar dropped his demand for extradition.

But just as a settlement was being reached, news arrived from Constantinople that Stratford Canning had improvised a reading of the 1841 Convention so as to allow the British fleet to move into the shelter of the Dardanelles if heavy winds in Besika Bay demanded this – exactly what transpired in fact when its ships arrived at the end of October. Nicholas was furious. Titov was ordered to inform the Porte that Russia had the same rights in the Bosporus as Britain had just claimed in the Dardanelles – a brilliant rejoinder because from the Bosporus Russian ships would be able to attack Constantinople long before the British fleet could reach them from the remote Dardanelles. Palmerston backed down, apologized to Russia, and reaffirmed his government’s commitment to the convention. The allied fleets were sent away, and the threat of war was averted – once again.

Before Palmerston’s apology arrived, however, the Tsar gave a lecture to the British envoy in St Petersburg. What he said reveals a lot about the Tsar’s state of mind just four years before he went to war against the Western powers:

I do not understand the conduct of Lord Palmerston. If he chooses to wage war against me, let him declare it freely and loyally. It will be a great misfortune for the two countries, but I am resigned to it and ready to accept it. But he should stop playing tricks on me right and left. Such a policy is unworthy of a great power. If the Ottoman Empire still exists, this is due to me. If I pull back the hand that protects and sustains it, it will collapse in an instant.

On 17 December, the Tsar instructed Admiral Putiatin to prepare a plan for a surprise attack on the Dardanelles in the event of another crisis over Russia’s presence in the principalities. He wanted to be sure that the Black Sea Fleet could prevent the British entering the Dardanelles again. As a sign of his determination, he gave approval to the construction of four expensive new war steamers required by the plan.

42

42

Palmerston’s decision to back down from conflict was a severe blow to Stratford Canning, who had wanted decisive military action to deter the Tsar from undermining Turkish sovereignty in the principalities. After 1849, Canning became even more determined to strengthen Ottoman authority in Moldavia and Wallachia by speeding up the process of liberal reform in these regions – despite his growing doubts about the Tanzimat in general – and bolstering the Turkish armed forces to counteract the growing menace of Russia. The importance he attached to the principalities was shared increasingly by Palmerston, who was moved by the crisis of 1848–9 to support a more aggressive defence of Turkey’s interests against Russia.

The next time the Tsar invaded the principalities, to force Turkey to submit to his will in the Holy Lands dispute, it would lead to war.

The End of Peace in Europe

The Great Exhibition opened in Hyde Park on 1 May 1851. Six million people, a third of the entire population of Britain at that time, would pass through the mammoth exhibition halls in the specially contructed Crystal Palace, the largest glasshouse yet built, and marvel at the 13,000 exhibits – manufactures, handicrafts and various other objects from around the world. Coming as it did after two decades of social and political upheaval, the Great Exhibition seemed to hold the promise of a more prosperous and peaceful age based upon the British principles of industrialism and free trade. The architectural wonder of the Crystal Palace was itself proof of British manufacturing ingenuity, a fitting place to house an exhibition whose aim was to show that Britain held the lead in almost every field of industry. It symbolized the Pax Britannica which the British expected to dispense to Europe and the world.

The only possible threat to peace appeared to come from France. Through a

coup d’état

on 2 December 1851, the anniversary of Napoleon’s coronation as Emperor in 1804, Louis-Napoleon, the President of the Second Republic, overthrew the constitution and established himself as dictator. By a national referendum the following November, the Second Republic became the Second Empire, and on 2 December 1852 Louis-Napoleon became the Emperor of the French, Napoleon III.

coup d’état

on 2 December 1851, the anniversary of Napoleon’s coronation as Emperor in 1804, Louis-Napoleon, the President of the Second Republic, overthrew the constitution and established himself as dictator. By a national referendum the following November, the Second Republic became the Second Empire, and on 2 December 1852 Louis-Napoleon became the Emperor of the French, Napoleon III.

The appearance of a new French emperor put the great powers on alert. In Britain, there were fears of a Napoleonic revival. MPs demanded the recall of the Lisbon Squadron to guard the English Channel against the French. Lord Raglan, the future leader of the British forces in the Crimean War, spent the summer of 1852 planning the defences of London against a potential attack by the French navy, and that remained the top priority of British naval planning throughout 1853. Count Buol, the Austrian Foreign Minister, demanded confirmation of Napoleon’s peaceful intentions. The Tsar wanted him to make a humiliating disclaimer of any aggressive plans, and promised Austria 60,000 troops if it was attacked by France. In an attempt to reassure them all, Napoleon made a declaration in Bordeaux in October 1852: ‘Mistrustful people say, the empire means war, but I say, the empire means peace.’

1

1

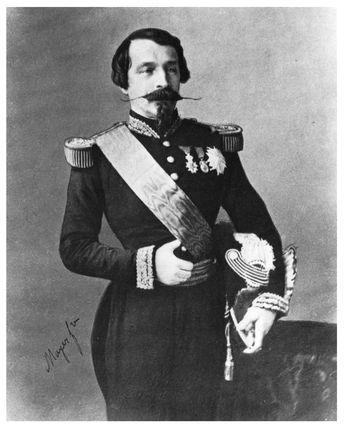

Louis-Napoleon, 1854

In truth, there were reasons to be mistrustful. It was hardly likely that Napoleon III would remain content with the existing settlement of Europe, which had been set up to contain France after the Napoleonic Wars. His genuine and extensive popularity among the French rested on his stirring of their Bonapartist memories, even though in almost every way he was inferior to his uncle. Indeed, with his large and awkward body, short legs, moustache and goatee beard, he looked more like a banker than a Bonaparte (‘extremely short, but with a head and bust which ought to belong to a much taller man’, is how Queen Victoria described him in her diary after she had met him for the first time in 1855

2

).

2

).

Napoleon’s foreign policy was largely driven by his need to play to this Bonapartist tradition. He aimed to restore France to a position of respect and influence abroad, if not to the glory of his uncle’s reign, by revising the 1815 settlement and reshaping Europe as a family of liberal nation states along the lines supposedly envisaged by Napoleon I. This was an aim he thought he could achieve by forging an alliance with Britain, the traditional enemy of France. His close political ally and Minister of the Interior, the Duc de Persigny, who had spent some time in London in 1852, persuaded him that Britain was no longer dominated by the aristocracy but a new ‘bourgeois power’ that was set to dominate the Continent. By allying with Britain, France would be able to ‘develop a great and glorious foreign policy and avenge our past defeats more effectively than through any gain that we might make by refighting the battle of Waterloo’.

3

3

Russia was the one country the French could fight to restore their national pride. The memory of Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow, which had done so much to hasten the collapse of the First Empire, the subsequent military defeats and the Russian occupation of Paris were constant sources of pain and humiliation to the French. Russia was the major force behind the 1815 settlement and the restoration of the Bourbon dynasty in France. The Tsar was the enemy of liberty and a major obstacle to the development of free nation states on the European continent. He was also the only sovereign not to recognize the new Napoleon as emperor. Britain, Austria and Prussia were all prepared to grant him that status, albeit reluctantly in the case of the last two, but Nicholas refused, on the grounds that emperors were made by God, not elected by referendums. The Tsar showed his contempt for Napoleon by addressing him as ‘mon ami’ rather than ‘mon frère’, the customary greeting to another member of the European family of ruling sovereigns.

h

Some of Napoleon’s advisers, Persigny in particular, wanted him to seize on the insult and force a break with Russia. But the French Emperor would not begin his reign with a personal quarrel, and he passed it off with the remark: ‘God gives us brothers, but we choose our friends.’

4

h

Some of Napoleon’s advisers, Persigny in particular, wanted him to seize on the insult and force a break with Russia. But the French Emperor would not begin his reign with a personal quarrel, and he passed it off with the remark: ‘God gives us brothers, but we choose our friends.’

4

For Napoleon, the conflict with Russia in the Holy Lands served as a means of reuniting France after the divisions of 1848–9. The revolutionary Left could be reconciled to the

coup d’état

and the Second Empire if it was engaged in a patriotic fight for liberty against the ‘gendarme of Europe’. As for the Catholic Right, it had long been pushing for a crusade against the Orthodox heresy that was threatening Christendom and French civilization.

coup d’état

and the Second Empire if it was engaged in a patriotic fight for liberty against the ‘gendarme of Europe’. As for the Catholic Right, it had long been pushing for a crusade against the Orthodox heresy that was threatening Christendom and French civilization.

It was in this context that Napoleon appointed the extreme Catholic La Valette as French ambassador to Constantinople. La Valette was part of a powerful clerical lobby at the Quai d’Orsay, the French Foreign Ministry, which used its influence to raise the stakes in the Holy Lands dispute, according to Persigny.

Our foreign policy was often troubled by a clerical lobby (

coterie cléricale

) which wormed its way into the secret recesses of the Foreign Ministry. The 2 December had not succeeded in dislodging it. On the contrary, it became even more audacious, profiting from our preoccupation with domestic matters to entangle our diplomacy in the complications of the Holy Places, where it hailed its infantile successes as national triumphs.

La Valette’s aggressive proclamation that the Latin right to the Holy Places had been ‘clearly established’, backed up by his threat of using the French navy to support these claims against Russia, was greeted with approval by the ultra-Catholic press in France. Napoleon himself was more moderate and conciliatory in his approach to the Holy Lands dispute. He confessed to the chief of the political directorate, Édouard-Antoine de Thouvenel, that he was ignorant about the details of the contested claims and regretted that the religious conflict had been ‘blown out of all proportion’, as indeed it had. But his need to curry favour with Catholic opinion at home, combined with his plans for an alliance with Britain against Russia, also meant that it was not in his interests to restrain La Valette’s provocative behaviour. It was not until the spring of 1852 that he finally recalled the ambassador from the Turkish capital, and then only following complaints about La Valette by Lord Malmesbury, the British Foreign Secretary. But even after his recall, the French continued with their gunboat policy to pressure the Sultan into concessions, confident that it would enrage the Tsar and hopeful that it would force the British to ally with France against Russian aggression.

5

5

The policy paid dividends. In November 1852 the Porte issued a new ruling granting to the Catholics the right to hold a key to the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, allowing them free access to the Chapel of the Manger and the Grotto of the Nativity. With Stratford Canning away in England, the British chargé d’affaires in Constantinople, Colonel Hugh Rose, explained the ruling by the fact that the latest gunship in the French steam fleet, the

Charlemagne

, could sail at eight and a half knots from the Mediterranean, while its sister ship, the

Napoleon

, could sail at twelve – meaning that the French could defeat the technologically backward Russian and Turkish fleets combined.

6

Charlemagne

, could sail at eight and a half knots from the Mediterranean, while its sister ship, the

Napoleon

, could sail at twelve – meaning that the French could defeat the technologically backward Russian and Turkish fleets combined.

6

The Tsar was furious with the Turks for caving in to French pressure, and threatened violence of his own. On 27 December he ordered the mobilization of 37,000 troops from the 4th and 5th Army Corps in Bessarabia in preparation for a lightning strike on the Turkish capital, and a further 91,000 soldiers for a simultaneous campaign in the Danubian principalities and the rest of the Balkans. It was a sign of his petulance that he made the order on his own, without consulting either Nesselrode, the Foreign Minister, Prince Dolgorukov, the Minister of War, or even Count Orlov, the chief of the Third Section, with whom he conferred nearly every day. At the court there was talk of dismembering the Ottoman Empire, starting with the Russian occupation of the Danubian principalities. In a memorandum written in the final weeks of 1852, Nicholas set out his plans for the partition of the Ottoman Empire: Russia was to gain the Danubian principalities and Dobrudja, the river’s delta lands; Serbia and Bulgaria would become independent states; the Adriatic coast would go to Austria; Cyprus, Rhodes and Egypt to Britain; France would gain Crete; an enlarged Greece would be created from the archipelago; Constantinople would become a free city under international protection; and the Turks were to be ejected from Europe.

7

7

At this point Nicholas began a new round of negotiations with the British, whose overwhelming naval power would make them the decisive factor in any showdown between France and Russia in the Near East. Still convinced that he had forged an understanding with the British during his 1844 visit, he now believed that he could call on them to restrain the French and enforce Russia’s treaty rights in the Ottoman Empire. But he also hoped to convince them that the time had come for the partition of Turkey. The Tsar held a series of conversations with Lord Seymour, the British ambassador in St Petersburg, during January and February 1853. ‘We have a sick man on our hands,’ he began on the subject of Turkey, ‘a man gravely ill; it will be a great misfortune if he slips through our hands, especially before the necessary arrangements are made.’ With the Ottoman Empire ‘falling to pieces’, it was ‘very important’ for Britain and Russia to reach an agreement on its organized partition, if only to prevent the French from sending an expedition to the East, an eventuality that would force him to order his troops into Ottoman territory. ‘When England and Russia are agreed,’ the Tsar told Seymour, ‘it is immaterial what the other powers think or do.’ Speaking ‘as a gentleman’, Nicholas assured the ambassador that Russia had renounced the territorial ambitions of Catherine the Great. He had no desire to conquer Constantinople, which he wanted to become an international city, but for that reason he could not allow the British or the French to seize control of it. In the chaos of an Ottoman collapse he would be forced to take the capital on a temporary basis (

en dépositaire

) to prevent ‘the breaking up of Turkey into little republics, asylums for the Kossuths and Mazzinis and other revolutionists of Europe’, and to protect the Eastern Christians from the Turks. ‘I cannot recede from the discharge of a sacred duty,’ the Tsar emphasized. ‘Our religion as established in this country came to us from the East, and these are feelings, as well as obligations, which never must be lost sight of.’

8

en dépositaire

) to prevent ‘the breaking up of Turkey into little republics, asylums for the Kossuths and Mazzinis and other revolutionists of Europe’, and to protect the Eastern Christians from the Turks. ‘I cannot recede from the discharge of a sacred duty,’ the Tsar emphasized. ‘Our religion as established in this country came to us from the East, and these are feelings, as well as obligations, which never must be lost sight of.’

8

Seymour was not shocked by the Tsar’s partition plans, and in his first report to Lord John Russell, the Foreign Secretary, he even seemed to welcome the idea. If Russia and Britain, the two Christian powers ‘most interested in the destinies of Turkey’, could take the place of Muslim rule in Europe, ‘a noble triumph would be obtained by the civilization of the nineteenth century’, he argued. There were many in the coalition government of Lord Aberdeen, including Russell and William Gladstone, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, who wondered whether it was right to go on propping up the Ottoman Empire while Christians were being persecuted by the Turks. But others were committed to the Tanzimat reforms and wanted time for them to work. Procrastination certainly suited the British, since they were caught between the Russians and the French, whom they distrusted equally. ‘The Russians accuse us of being too French,’ the astute Queen Victoria remarked, ‘and the French accuse us of being too Russian.’ The cabinet rejected the Tsar’s notion that an Ottoman collapse was imminent and agreed not to plan ahead for hypothetical contingencies – a course of action likely in itself to hasten the demise of the Ottoman Empire by provoking Christian uprisings and inspiring repressions by the Turks. Indeed, the Tsar’s insistence on an imminent collapse raised suspicions in Westminster that he was plotting and precipitating it by his actions. As Seymour noted of his conversation with the Tsar on 21 February, ‘it can hardly be otherwise but that the Sovereign who insists with such pertinacity upon the impending fate of a neighbouring state must have settled in his own mind that the hour of its dissolution is at hand’.

9

9

Other books

Detective by Arthur Hailey

Project Ouroboros by Makovetskaya, Kseniya

Serpent's Tower by Karen Kincy

Blood Will Have Blood by Linda Barnes

The Grave Gourmet by Alexander Campion

The October Light of August by Robert John Jenson

Rev It Up by Julie Ann Walker

Moon's Choice by Erin Hunter

Ashwood Falls Volume Two by Lia Davis

Doctor Who: Rags by Mick Lewis